The ECB Risks Busting European Banks

While some are anxiously waiting for an expansion of the current European QE programme, others are praying for that not to happen. At this point, an expansion of QE and a further interest rate cut may act as dynamite for European banks and do little for investors. Banks stand to lose profitability if the European economy doesn’t recover quickly and/or the ECB insists in busting them through the use of negative rates.

Investors in general take any news about QE with a smile. After all, the increase in demand coming from the central bank would push asset prices higher and help fatten investors’ profits. But, as we have seen with crude oil, there are limits to the upside potential and not everything that comes with more favourable prices is good. Lower oil prices mean lower gasoline prices, lower production costs and then higher purchasing power for consumers. At a time of global recession that should be more than welcome. But then we quickly find that there is a point at which the benefits become pernicious and lower oil prices do more harm than good. Investors now pray for higher oil prices as that seems to be the only way to keep equities rising. By analogy, a similar situation occurs with low interest rates. A rate cut when rates are high acts like a charm on a depressed economy. But when central banks insist in cutting them ever more, a point comes where more harm than good comes from a marginal cut.

It is usually said that a bank’s profitability increases with interest rates. The rationale is straightforward. Retail banks, commercial banks, brokerages, investment banks, insurance companies and other institutions, all accept deposits (or other forms of cash) from clients. In possession of such massive amounts of cash, these institutions need to get some yield from it. The trick is to pay their clients, for their money balances, less than what they can get from depositing the balances at the central bank and from lending them in the overnight interbank market. When central banks raise their rates, banks stand to earn some extra yield on these balances and usually experience an increase in profits.

One could argue that, as long as banks pay their clients less than they receive from the central bank, there’s no need to worry about the specific level of interest rates. After all, the bank makes money from a spread. But the main problem is that the bank is unable to keep the spread unchanged, as it tends to decrease along with interest rates. In particular, in the case of rates approaching the zero lower bound, it is easy to understand why margins erode. When central bank rates approach zero or turn negative, banks vacillate to pass them on to clients.

But banks don’t just take deposits from clients; they lend money to their clients. When rates are low, banks can eventually increase their lending spread and increase their profitability. That is eventually possible, but the expected lending volume in periods that rates are low is also low. Theory claims that the lower the interest rate, the higher the demand for funds; but unfortunately, low rates and a depressed economy usually coexist, which completely distorts the relationship. Central banks usually cut rates when economic conditions are bad. While a bank might be able to increase its lending spread, it is unlikely it would find as many solvent borrowers as it would when the economy was booming (which would most likely coincide with higher rates). Overall, profit from lending activities is then expected to decrease, not rise.

In general, banks can then increase profitability when the economy is booming, which usually coincides with an environment where rates are high.

Now let’s consider a period in which a central bank cuts its key rates to a negative value, as is currently the case with the ECB, the SNB, the BoJ, and many others. Currently the ECB offers a -0.30% rate on its deposit facility. Banks keeping cash balances at the ECB will have to pay for it. This acts like a tax on parked bank balances. If banks could pass this cost to their clients, their profitability wouldn’t be affected. They could pay 0.30% to the central bank and eventually charge 2.30% to their clients. But banks fear that, as soon as they charge deposits, clients would withdraw their existing balances, convert them into physical cash, and keep that cash ‘under the mattress’.

Under the above conditions, the impact of negative rates on banks’ profitability may be substantial. Banks accept deposits from clients, are charged to keep the balances at the central bank and are unable to charge clients. Banks are then losing money.

The reader may now be thinking that negative rates are a great incentive for banks to lend money. Banks can charge borrowers a positive rate while getting the money almost for free from the central bank, the interbank market and clients’ deposits. The bank would then make a profit. But, as I mentioned before, when rates are that low, it is likely the economy is under recessionary conditions. The central bank sets such low rates because it feels the economy needs a serious boost. One question that then arises is: are banks able to find a large number of solvent borrowers under these conditions?

In particular, after a financial crisis that ended with banks having to be bailed out to avoid bankruptcy, I wonder whether it is wise to believe banks would jump into a lending spree just because they have access to funds at a cost near zero. Even if they were willing to lend more, they would still need to find interested borrowers, which aren’t that many. The final result is very well expressed in the ECB balance sheet.

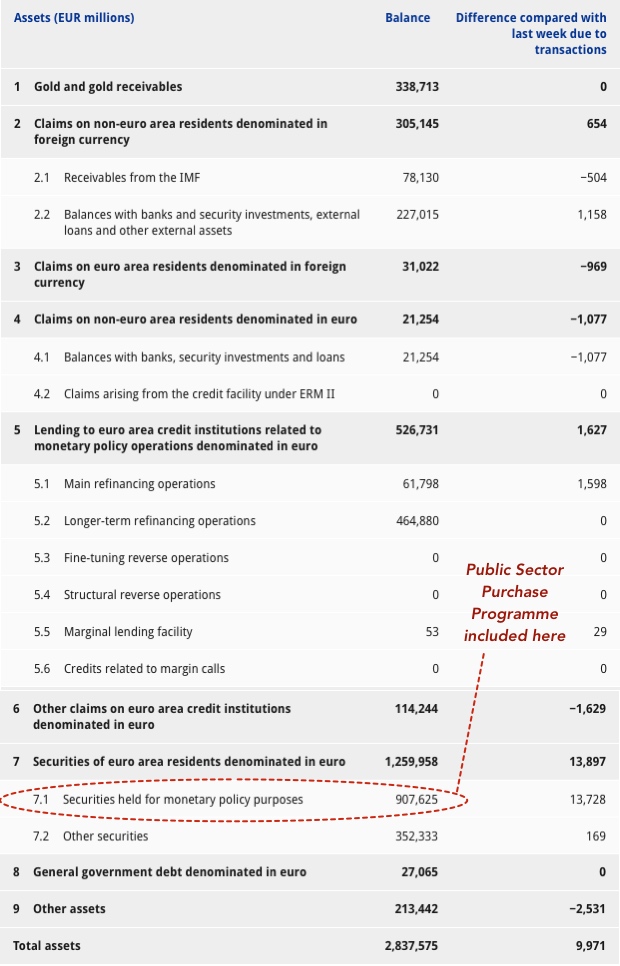

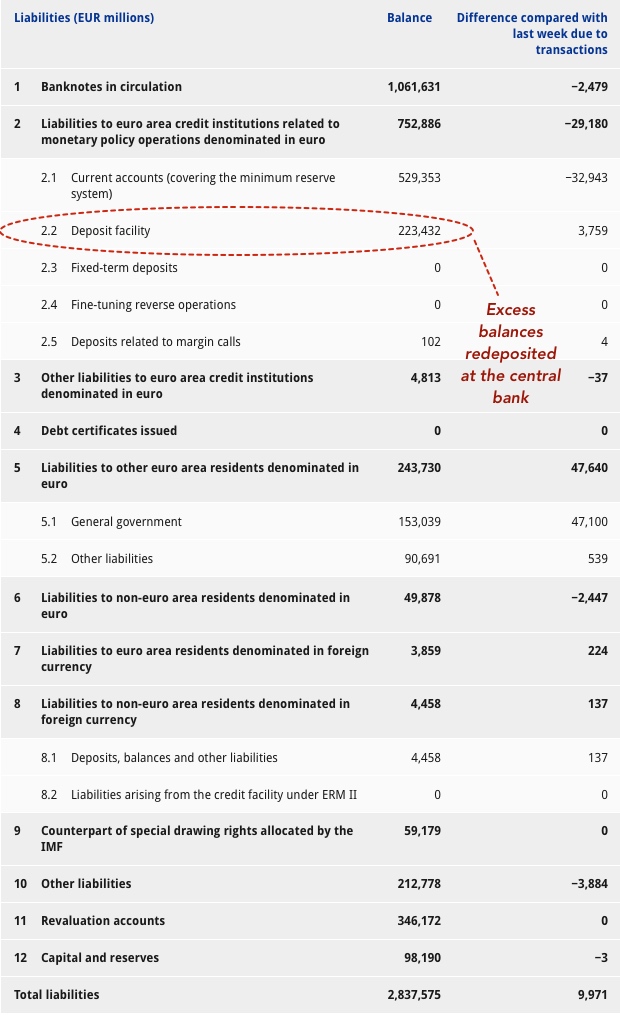

Instead of lending the money, European banks currently hold €223.4 billion in the ECB deposit facility. To put this into perspective, securities held for monetary policy purposes amount to €907.6 billion. The specific part that is relative to the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP – the European QE programme) amounts to €582.6 billion. A significant part of the money injected by the central bank just ends up parked at the central bank. This is a clue that banks are not finding alternative ways to put the excess money to use.

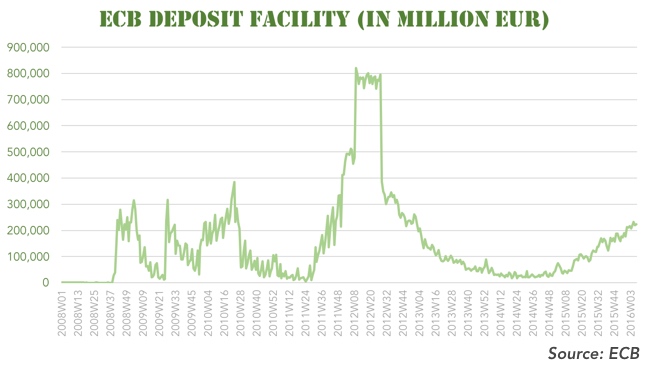

During the banking and sovereign crisis, the deposit facility hit a record level north of €800 billion. By then, the European Union was in serious trouble, with sovereign debt at risk of a default in some peripheral countries, while the economy was depressed. With sovereign bonds not being as safe as before, and lending activities severely depressed, banks had no other option than to deposit all liquidity back at the central bank. As Draghi promised to do “whatever it takes”, this situation was surpassed and money parked at the deposit facility decreased to just €17 billion in mid-2014. But the figure is now rising quickly again. With the European economy still a mess and global risks increasing since mid-2015, banks are not finding any good uses for their cash balances. A further cut to the deposit rate will most likely dent European banks’ profitability instead of helping the economy to recover. Because I believe the ECB will expand its asset purchase programme and further cut the deposit facility rate in its next meeting this month, I’m really bearish on European banks. The sector will be in trouble in 2016 and the figure of the bailout will resurface at some point.

A recent study from the BIS, conducted by Borio, Gambacorta and Hofmann (2015) corroborates this idea as the researchers claim that decreasing interest rates have a negative impact on banks’ profitability as the negative income generated outpaces any positive impact on loan loss provisions. Like I said, there is a point at which negative rates do more harm than good. The ECB will only stop when European banks are hit hard.

To read more about the woes of the European banking sector, read our upcoming issue of Master Investor Magazine – out on Friday!

Comments (0)