Don’t Fight the Fed, Fight the ECB

While central bankers look tranquil and trustworthy on their television appearances, giving investors reassurances that a brighter future is just around the corner and praising their timely and bold policy actions, there is a growing number of other professionals that still raise questions about the real effectiveness of such action and that are not at all convinced that a peaceful future is waiting to embrace us. These professionals fear that central bankers have created an addiction that will be difficult to get rid of and that ultimately will kill the patient.

Looking at the US economy, the headline numbers look good. Just take the unemployment rate as an example. It is currently pointing to 5.5%, which is near its full employment level, meaning the economy is operating near its full capacity. If we filter the numbers to include only college graduates, the percentage of unemployed decreases to a tiny 2.5%, reflecting an economy where a job is found with relative ease.

Even after discounting the latest negative surprise for GDP (growing at a modest 0.2% in Q1 2015), the above numbers show a great improvement over the depressed economy that followed the Lehman Brothers collapse. This is certainly the result of a mix of factors in which we have to include the bold and timely intervention orchestrated by Ben Bernanke when he was the chairman of the Fed.

But, even roses have thorns! Martin Feldstein, professor of economics at Harvard, believes that full employment has been achieved at a cost that may be substantial. He claims that financial risks are increasing due to an excessive use of easy monetary policy. Inflation has been subdued so far but mostly due to temporary effects that will soon reverse and cause trouble for the Fed if they delay action for too long. The quick decline in oil prices and a stunning appreciation of the dollar have both contributed to declining prices. But these factors have just postponed an inevitable rise in prices, as inflation pressures increase when full employment is achieved.

While Feldstein’s words make sense to me, they seem pretty much worthless for Janet Yellen, who just kicked the can down the road once again, pushing out the inevitable hike in interest rates to later in the year or even to next year. It is better to wait than to risk throwing the economy into recession, she believes. So, it is better to move very slowly, without any hurry.

The problem is that the longer the Fed takes, the greater the risks. It is not only about inflation but also about price bubbles. Bond prices are too high and do not reflect an expectation for inflation to normalise over the next few years. The reason is not because investors believe inflation will continue to be subdued but rather a result of too much asset purchasing by the central bank(s). When that happens for a prolonged period of time, there is only one direction prices can take when the music stops. Investors will face heavy losses on their portfolios and I’m really concerned with pension funds from that group.

While the US tries to improve its current conditions at the cost of the future, let’s take a look at Europe. Here the situation is not bad but tragic. The ECB is experimenting with its own version of large-scale asset purchases, commonly known as Q€, under which the central bank is willing to add €60 billion per month to its balance sheet over the course of almost two years. But the conditions under which the ECB operates are much more adverse than those faced by the Fed. Just to mention a few:

(1) It is too late – and thus yields are already too low, which can prevent the ECB from being successful at times.

(2) There is strong opposition to the programme – the ECB’s largest member is strongly against it.

(3) There is no single bond market – there is no such thing as a bond issued by the Euro Zone government but rather bonds issued by 19 different governments.

(4) There are massive economic differences between countries – with southern European countries facing a very different reality than the core.

All of the above represent massive challenges for the ECB, which can lead to very different results from those achieved in the US. But, roughly, the idea seems good: the central bank buys government debt, leading to a decrease in yields; then investors seek extra yield on riskier assets driving equities higher; and, in the end, the wealth created will push real investment and employment higher.

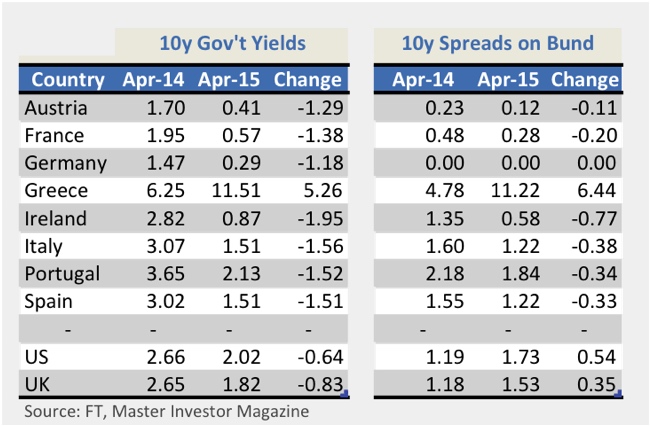

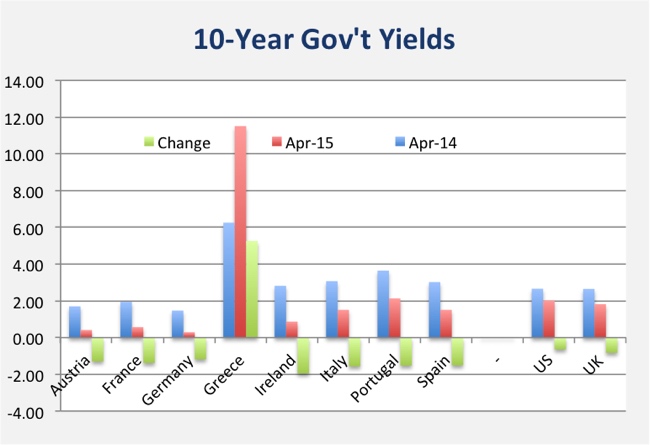

But again, there are some thorns in the path. As the yields were already low when the ECB announced its programme, they turned negative in the meantime. A complete mess set in in Europe. The Swiss National Bank ended its support for the euro at 1.20 to the franc and set negative interest rates, leading to a stunning appreciation of the franc. The Nordics followed a similar path in a desperate attempt to avoid an appreciation of their currencies. Some banks are even charging deposits from their clients. What was seen as impossible – setting interest rates at a negative value – is now a reality in Europe. More than 30 percent of all government debt in the Euro Zone (around €2 trillion of securities) is now trading on a negative yield. Yields are negative in most short-term issues and in some long-term ones. The yield on a 10-year Swiss bond is negative and on the equivalent German bond is near zero, which doesn’t properly reflect inflation expectations.

While I believe inflation may not be a concern in the very short-term, I agree with Feldstein’s view that a price increase has just been postponed. In the case of Europe, where the euro has been battered down, inflation may be just around the corner, a reality that is not reflected in the current negative long-term yields.

But for those who believe inflation will remain subdued, there is still an unexplained event, at least in rational terms. Seventeen percent of Spanish government bonds trade with negative yields. For a country that was near defaulting on its debt obligations just a few years ago, that is quite an achievement! In fact bond yields have not only decreased for most Euro Zone countries but the spreads over a German Bund have also decreased.

There are only two possible explanations:

- Risks have effectively reduced in peripheral countries to the point that they are not significantly above the core country risks anymore. The Euro Zone is then a more homogeneous place today and investors are happy to receive just a small premium over the German bonds to purchase Portuguese or Spanish bonds.

- The ECB distorted risk perceptions to the point that investors ignore different risk profiles and buy Spanish, Portuguese and German bonds interchangeably, as they believe the ECB caps any potential losses.

While the Portuguese and Spanish Prime Ministers are strong advocates of the first explanation; economic reality tilts in the direction of the second, as these countries’ debt to GDP levels have not improved much (if anything) over the last few years. So, risks decreased because someone is taking them – the ECB.

With the ECB buying bonds up to a negative yield of -0.2%, investors quickly jumped into the asset class, not because they believed they would earn a decent yield but rather because they thought they could sell them at a higher price to the ECB. While the ECB continues with its programme and bond yields are higher than -0.2%, we can only expect speculators to jump to ever more depressed and flattened yields. In the limit a Portuguese bond would trade at the same price as its German equivalent, in particular if the supply of safer bonds is scarce. This movement represents a complete detachment of prices from intrinsic value and is a huge threat to institutional investors like pension funds. While there is a saying advising “Don’t fight the Fed”, the transposition of it to the ECB’s world would most likely state “Do oppose the ECB as much as you can”.

Bill Gross believes the ECB intervention represents “the short of a lifetime”, as bonds are poised for a downhill race. With yields near zero, it costs almost nothing to short them in the short run while there’s potential to earn something if the yields rise. As the ECB provides downside protection on yields (capping its purchases at a -0.2% yield), the short sellers have a rare opportunity to experience unlimited upside with limited risk.

While the ECB is depressing the government bond yields, US companies are taking the opportunity to get some serious financing in European markets. In a movement known as reverse yankees, companies like Berkshire Hathaway, Kellogg, General Mills, Moody’s, and Coca-Cola are issuing bonds in European markets to benefit from the cheap financing. The same feeling is not shared by investors who bought them just to lose money, as prices suddenly dropped.

Thanks to central banks we have a great opportunity to short bonds, as the risk of doing it is very low. While buying bonds was the best business before the ECB announced Q€, now going in the opposite direction of the ECB is the only profitable solution. For those who want to take the extra mile like John Paulson and Paolo Pellegrini did in 2005-2007, there’s even more money to make buying credit default swaps. Just wait for a mix of negative events like Greece leaving the euro, oil prices rising, and inflation picking up, and you will see what happens to this massive fictional risk-free fairy tale in which we live.

Comments (0)