Is the Outlook Really as Bad as It Seems for the Banking Sector?

I’m not really a bank investor but when everybody is pessimistic about European banks, the alarm bells ring in my head and I’m tempted to oppose the herd. If there’s profits to be made, it is often via the ugly improving to just bad and not so much via the good improving to even better. Banks are caught in tough economic conditions, their share prices are depressed, and their business models need a revamp; but they’re still in much better condition today than they were in 2011-12 during the sovereign debt crisis. Maybe it is too soon, but I feel we may be approaching the time to add some European bank shares to the portfolio and keep them for quite some time. I believe we are approaching the end of the line for monetary policy rate cuts, which have been depressing banks’ profits and doing nothing for the consumer, while some fiscal measures may start to replace them and seriously boost demand.

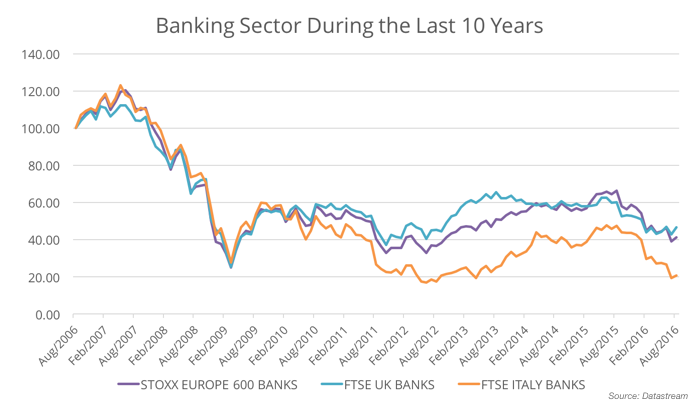

If we compute the total return provided by the STOXX Europe 600 Banks Index, the FTSE UK Banks Index and the FTSE Italy Banks Index for the last 10 years, we end with the following numbers: -58.8%, -53.3% and -79.3%, respectively. If we instead take the worst of the sovereign crisis as our basecamp, prices are up by 26%, 15% and 23%, respectively; but such numbers seem light given the previous losses and, in particular, the improving solvency conditions in the sector. The 48 European banks that are part of the Stoxx 600 Banks Index (which includes UK banks, by the way) currently trade on an average price-to-book ratio of 0.69, which means that, on average, banks are destroying shareholder value every time they spend/invest one euro or one pound. Banks are worth more dead than alive.

Given the average price-to-earnings ratio of 11.45x for these 48 banks, the current profit to book value of banks is around 6%, which seems pretty good given the 0.40% return an investor would obtain on a 30-year German bond. The truth is that the sector still has problems and many banks still carry doubtful loans on their balance sheet, but the latest stress tests show that insolvency is no longer a risk for European banks, as even in the worst case scenario of the tests (conducted on July 29th), all of them kept positive capital ratios (with the exception of Monte dei Paschi). The latest stress tests showed that, on aggregate, European banks are in much better shape than they were at the time of the last stress tests, in the autumn of 2014. The test led to a reduction in banks’ capital ratios from 12.6% to 9.2%, which compares with a decline from 11.1% to 7.6% in 2014. Not only did banks depart from a bigger capital cushion but they also ended up in much better condition than before. Ireland showed the worst average results, with the capital ratio at 5.2%. But I’m not overly concerned, as the country is growing much faster than the EU as a whole, with expected growth rates for this year and the next of 4.9% and 3.6% respectively, which will have a positive impact on its banks. If there’s something banks need, it is growth and demand, not liquidity.

The stress tests excluded banks from Portugal, Greece and Cyprus. Had they entered the tests, the results could have been worse. But, unlike 2011-12, systemic risk is low. Even if some banks are not in the healthiest of conditions in those countries, there is no material risk of a potential insolvency leading to another banking crisis at the European level, at least not in Portugal, Greece or Cyprus. The main conclusion from the stress tests is that banks are in good shape regarding their capital cushions to deal with some potential ugly scenario. They’re solvent! So, that’s good news, after all.

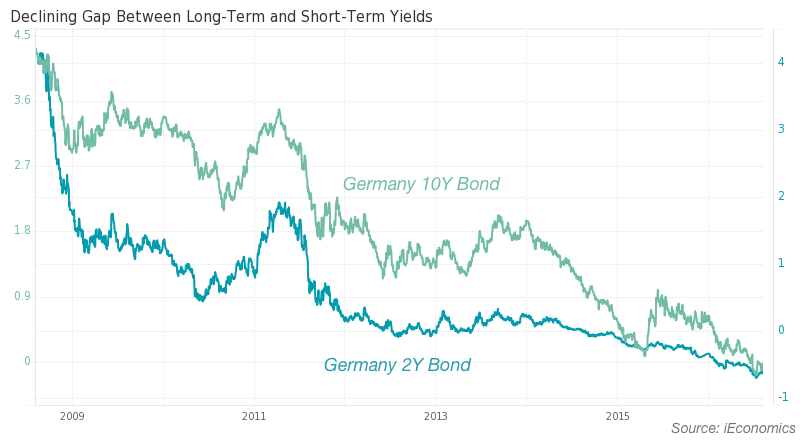

But the banking problem is not just related to their potential downfall due to an inability to deal with bad loans. In Italy, bad loans may indeed be a problem in the short term, but that isn’t the biggest concern today. What should worry investors is banks’ profitability. Banks make a profit from the existing gap between short-term interest rates, at which they borrow from the central bank, and long-term interest rates, at which they lend. If the gap shrinks, so does their profit margin. In a world where central banks keep their rates at very low levels while purchasing long-term government debt, it’s difficult to do business.

The central bank should only provide liquidity as needed and never use monetary policy as a way of boosting demand, because it is ineffective. At these low rates, it is even ineffective as a means of boosting inflation, because most of the impact is felt in asset prices. But if liquidity was needed in 2008 after the Lehman collapse and during 2011-12 when Greek banks were collapsing, it wasn’t thereafter. Banks have plenty of liquidity and they can always get more from the central bank. The problem, as has often been pointed out at Master Investor, is demand. Banks have a hard time trying to find solvent borrowers, not getting funds to lend. This means that what Europe needs is a boost to demand, which is better achieved through fiscal policy.

Policymakers are nearing a point at which it is becoming more than obvious that central banks can’t do anything for the economy without the help of government policy. I expect the EU to change its tough stance and to leave room for the adoption of some fiscal measures aimed at boosting the depressed European economy. This will help demand – and banks, too.

While banks are not really in a healthy position, I believe the market has overreacted. Most of the banks are now trading at values that make them more valuable if sold off piecemeal than as going concerns. But many banks have reduced the huge amount of bad loans they had during 2011-12 and are currently well capitalised. They still need to improve their top line, where the net interest margin is being challenged by a declining gap between long-term interest rates and short-term interest rates, but I believe things cannot deteriorate much further. ING (AMS:INGA), Crédit Agricole (EPA:ACA) and SocGen (EPA:GLE) recently posted strong quarterly results; Standard Chartered (LON:STAN) has made good progress on cost cuts; and some larger banks are even promising to return cash to shareholders (e.g. HSBC (LON:HSBA)). It is when everybody is pessimistic that there are larger profits to be made. I believe it is time to add some banks to the portfolio. One option is to select specific banks, which has its own risks. A better option could be to buy the sector and avoid the idiosyncratic risk involved in individual choices. A possibility is to buy an ETF mirroring the performance of the Stoxx Europe 600 Banks Index. There are several options out there. From the perspective of someone trading in sterling, one option could be to purchase the db x-trackers DJ Stoxx 600 Banks.

Comments (0)