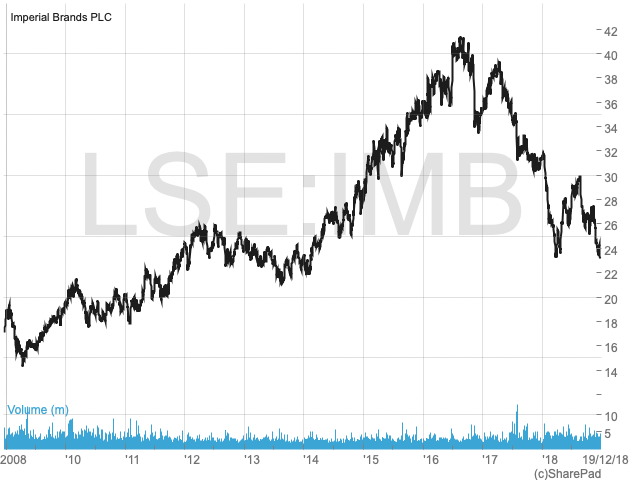

Is Imperial Brands the ultimate dividend-paying cigar butt?

The tobacco industry appears to be in terminal decline. Annual global cigarette volumes have consistently shrunk over the last few years and the number of countries with plain packaging laws has gradually increased. This is obviously bad for the long-term future of tobacco companies like Imperial Brands (LON:IMB) (formerly Imperial Tobacco). So bad in fact, that the company currently has a dividend yield north of 7%. With such a high yield, many investors will assume that a dividend cut is imminent, but I’m not so sure.

I’m not sure because a company in terminal decline is not necessarily a bad investment. After all, both Warren Buffett and Ben Graham spent many years as ‘cigar butt’ investors, buying businesses with terrible long-term prospects at extremely low prices (like cigar butts found in the street) and offloading them for a small profit at the first sign of optimism (akin to taking a single ‘free’ puff).

So is Imperial Brands a high yield cigar butt offering a hearty but relatively short-lived dividend drag, or is it a yield trap offering a huge dividend which will never be paid? Let’s take a look.

A consistent record of growth in a declining market

As seen in Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

Starting at the top of the income statement, Imperial Brands has increased its revenues per share by about 12% over the last decade, giving an annualised growth rate of 1.6%. That’s pretty weak and fails to keep up with inflation.

Turning to reported earnings per share, they’re down over the last ten years by a few percent. And just as worrying, those earnings have failed to cover the dividend in six out of the last ten years. That’s just about the last thing a dividend investor wants to see in a company, so at this stage it seems as if yield trap may be a better description than (the not exactly flattering) cigar butt.

However, in this case, reported earnings may be more misleading than they are helpful. The reason goes back more than ten years ago to when Imperial Tobacco (as it was then) was an aggressively acquisitive company looking to become a big player in the global tobacco scene.

Acquired goodwill and the distorting effect of amortisation

After re-joining the stock market as an independent company in 1996 (following ten-years as a wholly owned subsidiary of Hanson Trust PLC), Imperial Tobacco spent more than £17 billion acquiring other companies en route to becoming the world’s fourth largest tobacco manufacturer. This acquisition spree ended in 2008, coinciding with the Great Financial Crisis. Since then, further acquisitions have totalled less than £5 billion.

What does all this have to do with misleading reported earnings? Well, as with most acquisitions, the price paid for these companies far exceeded their tangible assets. After each acquisition, the premium paid above tangible assets ended up on Imperial’s balance sheet as accounting goodwill, an intangible rather than tangible asset. That’s relevant because intangible assets are, for the most part, depreciated over anywhere from three to 30 years, just like tangible assets (although for intangibles it’s called amortisation). Eventually, Imperial Brands ended up with more than £20 billion of intangible assets and that requires a lot of amortisation.

Amortisation is a non-cash expense which reduces the company’s profits by varying amounts, but it currently runs close to £1 billion per year. That’s a big recurring non-cash expense, especially for a company where pre-amortisation profits are only around £3.5 billion. The result of so much amortisation is that the company’s dividend is often uncovered by reported earnings, but only because of a huge non-cash expense largely caused by acquisitions made more than a decade ago.

To get a better view of Imperial Brands, I think (and following in the footsteps of a certain Mr Buffett) a more accurate picture of a company’s operating performance is given when amortisation is excluded from earnings. There are various ways to do this, but one simple approach is to look at free cash flow instead of reported earnings.

As seen in Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

Free cash flow is an attempt to measure the amount of cash generated by the company’s business operations (known as net operating cash flow), minus any cash reinvested into the business to pay for new capital assets such as property, plant and equipment (otherwise known as capital expenses or capex).

Like any performance measure, free cash flow isn’t perfect, but it does exclude Imperial’s huge non-cash amortisation of goodwill expense. It also replaces the non-cash expense of deprecation (which reflects the reduction in historic value of old capital assets) with the cash expense of capex (which reflects the current cost of new capital assets). Replacing depreciation with capex is generally a conservative move because capex is usually a larger expense than depreciation. That’s because a) growing companies will usually be investing more in fixed assets today than they were five or ten years ago and b) the cost of replacing assets goes up over time thanks to inflation.

More generally, free cash flow is probably a better measure than reported earnings if you’re looking for reliable dividend payments.

Growing free cash flow easily covers a progressive dividend

Unlike reported earnings which are down over the last decade, Imperial Brands’ free cash flow per share has increased by more than 30%, with an annualised growth rate of 4%. That’s better than the company’s 1.6% annualised revenue growth and reflects increasing margins thanks to the company’s focus on cost cutting and higher margin products.

More importantly, free cash flow has covered the dividend every year, with an average free cash flow dividend cover of 1.9. Free cash flow dividend cover has been decreasing, though, going from around 2.5 a decade ago to 1.5 today. The reason is that management has seen fit to increase the dividend by an average of almost 11% per year for a decade. This makes for happy shareholders, but it isn’t sustainable. At some point in the next few years the dividend’s growth rate will have to be reduced if it’s to remain well-covered by free cash flows.

Extraordinary returns on tangible capital employed

One thing you can say about the tobacco industry is that it’s spectacularly profitable. That’s because smokers are relatively insensitive to price increases and the price charged by tobacco companies is often only a small percentage of the price paid by consumers.

As seen in Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

For example, in the UK, tax typically makes up 80% to 90% of the price of a pack of 20 cigarettes. Under the current tax rules, if Imperial charged £2 for a pack of 20, the retail price would be £9.18 thanks to fixed and variable tobacco duty and VAT. If Imperial increased its price by 10% to £2.20, that would increase the retail price from £9.18 to £9.46. For most companies, a 10% price increase would drive customers away towards cheaper competitors, but most smokers I know would be unlikely to quit or change brands because of a 28p price rise. And that, in a nutshell, is the sort of pricing power Tesco or Balfour Beatty would kill for.

This pricing power translates into extreme levels of profitability. By ‘profitability’ I mean free cash flow return on tangible capital employed. It’s a bit of a mouthful, but the basic idea is simple. Since we’re ignoring amortisation of acquired intangible goodwill (by using free cash flows instead of reported earnings) it makes sense to ignore those same intangible assets which are largely made up of goodwill. This will allow us to see what sort of return the company makes on the actual physical assets it uses to generate those returns, i.e. factories, cigarette manufacturing equipment, etc. It’s the sort of return the company might make on a new factory built to increase production.

In contrast, including intangibles in the capital employed figure would show us the sort of return the company makes on the total amount of capital invested by management, including large acquisition which may have been made ten or twenty years ago.

I’m interested in the return the company can make on the cash invested in new fixed assets today, not what the return is on an acquisition made by a long-gone CEO ten or twenty years ago. And that’s why I’m looking at the free cash flow return on tangible capital employed.

Over the last ten years, Imperial Brands has generated average free cash flows of £2.4 billion per year. During the same period, it had on average £2.5 billion of tangible capital employed. That’s an astonishing 96% free cash flow return on tangible capital employed.

Generating annual free cash equal to almost 100% of tangible assets employed is something very few companies can do. Such high returns on tangible capital means that Imperial Brands can grow while reinvesting just 11% of its operating cash flow back into the business as capex. The rest is available for acquiring other businesses, paying down debt, buying back shares or putting dividends into the pockets of shareholders.

Large debts and a plan for reducing them

As seen in Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

One negative aspect of Imperial Brands (other than the obvious health costs of its highly addictive products) is its relatively high debt levels. At £12 billion, the company’s total borrowings are about five-times its ten-year average free cash flows of £2.4 billion. That’s about as much as I’d be willing to call prudent, despite the stability and defensiveness of the tobacco market.

However, this isn’t quite enough to put me off because the company has a plan to substantially reduce its debts in the years ahead. This debt reduction will be driven to a large extent by a series of large divestments which are expected to generate around £2 billion of cash. This divestment plan is important because it’s a key part of the company’s strategy for succeeding in an ever-shrinking tobacco market.

Multiple tactics for coping with a shrinking tobacco market

Smoking is in decline around the world, which is good for all those people who won’t be dying of lung cancer, but bad for companies like Imperial Brands. The global market for cigarettes and other tobacco products has been declining by a few percent each year, and that makes it hard to see how Imperial Brands and the other tobacco companies can continue to deliver dividend growth.

But there are ways to avoid declines in the short, medium and perhaps even the longer-term. There are a range of options, including: moving customers from low margin brands to high margin brands; moving customers from declining brands to growing brands; increasing market share; increasing prices; cutting costs and increasing efficiency; divesting from declining and non-core brands; investing more behind growth brands; buying back shares; paying down debts; acquiring other tobacco companies and investing in non-tobacco products.

Imperial Brands is doing all the above and more. It’s a long list, so I’ll just focus on a couple of major tactics.

Moving customers onto higher margin growth brands

Imperial Brands has dozens of cigarette, cigar and tobacco brands in its portfolio, some of which are both well-known and sold across the globe (such as Davidoff, JPS and West) while others are obscure and sold in a limited geographic region.

As seen in Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

The big global brands tend to be higher margin and higher growth, so it makes sense to transition customers from lower margin regional brands to the global growth brands. This increases the geographic spread and market share of the growth brand and is more efficient because it reduces the number of packet designs, cigarette ingredients and, potentially, layers of management.

The idea is to take a local brand (say, Brand X) where you want to transition the customers and stick “by JPS” (for example) on the label underneath the main brand name. After a while, customers get used to seeing JPS on the label. If sales numbers are holding up, you can then switch the brands around so that the main brand name is JPS and it’s subtitled “by Brand X”. Then you can change the rest of the packet design and eventually it looks the same as a packet of JPS from anywhere else in the world. I don’t know for sure, but I assume they do something similar with the ingredients and flavour to maximise economies of scale.

Investing in non-tobacco alternatives

Non-tobacco Next Generation Products (NGP) is where most of the current speculation around tobacco companies is centred. Will Big Tobacco be able to convert billions of smokers into billions of ‘vapers’, or not? I have no idea, but if they can it’s going to take a very long time. There are, however, some encouraging early signs.

For example, in 2018, Imperial Brands’ net revenues (after tobacco-related taxes) were up by 2%, with 1% coming from tobacco products and 1% coming from NGP revenue growth. That’s impressive, especially given the small size of the NGP business.

How small? Well, management hope that NGP net revenue can grow by up to 150% per year, which would see it reach £1.5 billion by the end of 2020. Compare that to the company’s current total net revenues of £7.7 billion and you can see that – even with super-optimistic growth rates – it will take the company’s non-tobacco products a long time to generate significant revenues and profits.

As for the profitability of those NGPs, I seriously doubt whether they’ll be anything like as profitable as the existing, highly polished and massively scaled cigarette business. The jury is very much out on this one as Imperial’s NGP business is still loss-making, thanks to massive investments to drive awareness and a lack of economies of scale.

Is this a profitable cigar butt or dangerous yield trap?

With a dividend yield of more than 7% and a long-history of 10% annual dividend growth, Imperial Brands is seriously attractive as a dividend investment. The key question of course is whether that dividend can keep going up, or whether it’s likely to stagnate or decline.

As seen in Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

Personally, I’m more of a tobacco optimist than a pessimist, at least for the next decade or two. Yes, the market is in long-term decline, but for now I think Imperial Brands has a good chance of more than offsetting those declines. It could do this by moving customers to higher margin growth brands, cutting costs, divesting non-core brands, investing in growth brands, investing in non-tobacco brands and buying back shares.

And while all the excitement is around non-tobacco alternatives because they’re shiny and new and look a bit like a tech product, I’d rather see the company focus on margin improvements, efficiency and maximising cash returns to shareholders via dividends and share buybacks. In other words, I’d rather see management extract the maximum amount of cash from a declining cigar butt business than invest shareholder funds into a highly uncertain and highly competitive non-tobacco future.

Either way, I think the decline of tobacco is going to take a very long time, so I’d be happy to invest in Imperial Brands at anything under 4,000p.

Very well written and researched article, I enjoyed your balanced view on IMB and the industry as a whole.

One thing ibthinknis also worh mentioning is the disproportionate profitability of the US market vs the rest of the world (about 5 time more profit per stick). In my opinion this is due to the much lower tax rate I the US compared to Europe, and much higher pricing power than in emerging markets. What are your thoughts on that?