It’s a technology bubble but not as we know it

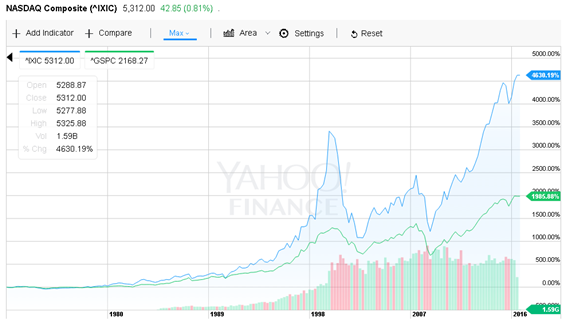

Are tech valuations supported by fundamentals or are we partying like it’s 1999? 16 years since the bursting of the dot.com bubble, when the Nasdaq Composite Index fell 37% in the 10 weeks following its peak on March 10, 2000, the continued stellar performance of tech stocks and startups is once again raising eyebrows in some quarters.

Calling asset bubbles is like Paul Samuelson’s oft cited joke about markets predicting nine out of the last five recessions. In other words, it’s easy to do but harder to identify in real time. Sometimes only hindsight gives us a clear view of past events. Bubbles are also relative. Markets are made by differences of opinion after all.

Caveats aside, there has been extensive recent discourse on internet and technology stocks being or not being (that is the question!) in bubble territory. So, are valuations out of step with reality? Let’s start by looking at the Nasdaq (IXIC), the traditional home for tech stocks:

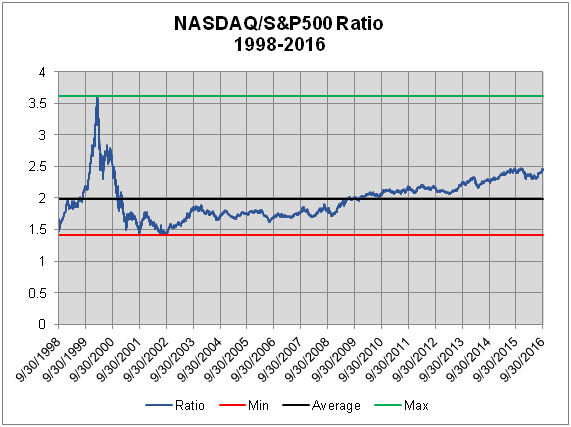

The index is (nominally) certainly way above its 2000 highs and it also looks like a sizeable gap is once again opening up with the S&P500 (GSPC). Crunching some numbers, the current level of the index pair is 24% above its 18-year average, but crucially, still 32% below peak bubble. We also need to factor in 16 years of inflation – today´s 5,000 points would be closer to 3,500 back then – as well economic growth over the period.

Nonetheless, “unicorns” – those privately held companies with valuations over $1bn – have gone from being mythical, elusive creatures to a growing reality. There are currently 178 in the “blessing” (the name for a group of unicorns) with total valuations of $628bn. Uber is now worth more than $60bn, Airbnb $30bn and Snapchat (who were deemed crazy not to accept a $3bn Facebook bid back in 2013) are now raising capital at a $20bn valuation. Alibaba’s $4.5bn private financing round valued the company at $60bn.

Needless to say, these are huge numbers. Investors’ Fear Of Missing Out (FOMO) on the next big thing also motivates investment decisions. Is this irrational exuberance recreating the noughties internet bubble or is there something else going on behind these numbers?

Let’s put these unicorn valuations into context. Uber, who doesn’t own cars and has negative earnings, is valued at close to Volkswagen (ETR:VOW3), the second largest car manufacturer in the world with annual revenues of over 200bn EUR and 150bn EUR in assets. Or take Airbnb, currently worth a similar amount to Marriot International (NASDAQ:MAR), the world’s largest hotel group without owning a single property.

The valuation narrative, arguably the most powerful driver of prices, seems then to be suggesting a new transformational paradigm. New technology, or rather new applications of existing technology, connects billions of customers to millions of products and services across the world, enhancing business efficiency and potential investment returns in its wake. Hence, increasing investor appetite and rising valuations as the demand curve shifts to the right. The tech giants are also increasingly expanding their reach into robotics, transport and energy.

So is this time different?

Up until around 2010, no fully VC backed company had ever been worth $1bn. One key difference then, led by the new unicorn wave, is that bubble conditions are focused on the private markets and not in listed indexes like Nasdaq or AIM.

The focus on private markets means it’s harder to track on a daily basis what’s happening to valuations. But it also means that it’s harder for private investors to join the party, further inflating prices, therefore potentially limiting bubble economics and contagion effects. That’s not to say that the broader financial markets are immune to any private tech downturn. The fall of Lehman Brothers showed the potential for systemic risk in today’s interconnected financial nexus.

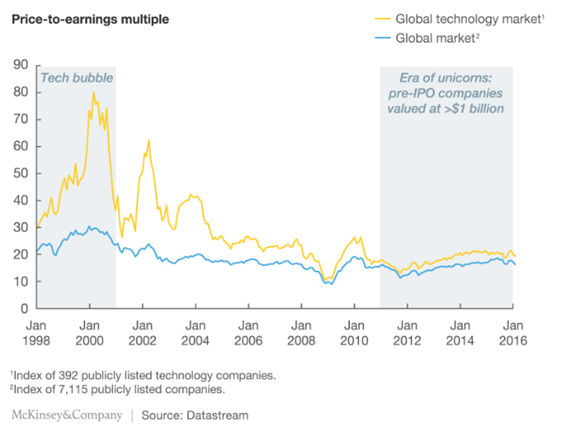

Although the Nasdaq Composite is hitting all-time highs, such momentum can be seen in most major indexes and broader asset prices. Welcome to an “everything bubble”. Nevertheless, with average P/Es of 20, today’s public tech valuations are roughly in line with global markets – especially considering their higher expected growth rates – and a long way off from average tech P/Es of around 80 at the height of the bubble.

Apple (NASDAQ: AAPL) is currently trading at 13 times forward P/E, Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG) at 30 times and Facebook (NASDAQ:FB) 21 times 2018 earnings. Cisco (NASDAQ:CSCO) was trading at 270 times the per-share earnings of the previous twelve months in 2000 when it was also, briefly, the largest company in the world.

There is a disconnect between public and private markets for sure, and any bubble discourse needs to reflect this new normal. Nonetheless, the public and private spaces don’t exist in isolation. Eventually the two should converge through listings or direct acquisition from public firms.

Data from Mckinsey also show that we are seeing shifts in the funding environment. The average VC investment more than doubled over the last four years. Burn rates are growing and new capital infusions are decreasing.

Is global venture funding reaching its limits? The number of pre-IPO financing rounds has also increased: firms are staying private for longer and attracting institutional investment instead of quick-fire listings. According to EY, there have been 75 IPO deals so far this year, compared to 140 during the same time period in 2015. Are firms and investors trying to delay or avoid the public markets making their judgment on unicorn valuations? Where are the Uber, Airbnb and Snapchat IPOs?

A lot of these headline “valuations” are often based on complex structures of downside protections built into investment terms, such as ratchets and features, convertible notes and multiple share classes rather than fundamental estimates of enterprise value. The motivational pull factors around “billion dollar” valuations and their impact on fundraising and publicity are strong. Maintaining positive momentum is key.

For unicorns then, the greatest threat isn’t the “B” word, but the “D” word – i.e. the dreaded “down round”. Such events, where valuations decline relative to previous rounds, increased to 57 from 22 y-o-y. Some notable unicorns that took big write-downs included Zenefits, Xiaomi, Flipkart, Jawbone and Foursquare.

Analytics firm CB Insights published its own Downround Tracker, a start-up death-watch list of at least 55 companies. If the backlog of IPO ready projects come on stream we could see lower pre-IPO prices, post-IPO volatility or a lack of upside.

Of the 32 technology companies that went public with downrounds since the start of 2012, 53 percent are trading below their IPO price, according to data from PitchBook. For a case in point, looking at Uber, Professor Damodaran, the global authority on valuation, has recently argued that the company should only be worth less than half of its current $60bn implicit valuation.

As is often the case, higher valuations without solid financials and especially the instant validation of public markets, can come back and bite you. A unicorn with say $1bn in revenue, rather than an explicit $1bn price tag would be a much more objective, and rarer, beast.

How did we get here?

A myriad of economic factors: zero interest rate policies, quantitative easing and increased digital inclusion of billions of consumers in emerging markets are all major drivers. It is also easier and less capitally intensive to launch tech startups than it was in 2000. No wonder then that large mutual funds like T. Rowe Price, and Fidelity have also been entering the private tech play over the last few years.

These unicorns, so the argument goes, are then finally delivering on the failed promise of the 1990s and valuations are merely reflecting this. As George Soros said, stock market bubbles don’t grow out of thin air. They have a solid basis in reality, but reality as distorted by a misconception. Perhaps in this case, the misconception is that disruption automatically leads to earnings.

The publicly traded tech giants of Amazon, Apple and Facebook all generate impressive earnings or cash flow and are now amongst the largest companies in the world. The major private companies eventually need to “show us the money” to justify their high valuations.

A decent definition of “bubble” then would be when price far exceeds the asset’s fundamental value, even factoring in a positive outlook. This seems to be the case with certain unicorns, but again it depends on the metrics and narrative you are employing. A few unicorns could indeed “grow into” their high valuations, go public and become hugely successful companies. But on the whole, potential can only trump reality for so long.

Logic dictates that eventually there will be a correction in unicorn prices, either due to economic factors (a downturn or rising interest rates) or perhaps if some of these firms are given a rude welcome by public markets. We cannot be sure what such a pullback will look like, or what kind of impact it will have other than the fact that it will certainly not be a carbon copy of 2000.

In some respects at least, it is different this time. For one thing, the digital and tech economy is much more ingrained and relevant in our daily lives. This secular trend will continue. We also – supposedly – have greater understanding of internet and tech business models and adequate valuation metrics.

However, to sum up, as Warren Buffett has said: “It’s only when the tide goes out that you can see who’s been swimming naked”. IPO aversion up to now and creeping valuation haircuts suggest that we could be about to discover who has been skinny-dipping.

Comments (0)