Staying private: the dynamics of public vs private capital in a changing world

By Martyn Holman, Partner at Augmentum Fintech

The world has changed radically over the last month. COVID-19 has negatively impacted lives and commerce the world over. The radical short-term transformations in global supply and demand have put most businesses into pause mode; one of the many consequences for startups and growth companies is likely to be a longer road to ultimate exit.

It’s in the data

Yet if we see IPO (Initial Public Offering) as the ultimate exit for a venture backed business, then this is not a fresh dynamic, rather part of a long-term trend. IPO has long been considered the holy grail for most founders. Traditionally it has been seen as the only mechanism capable of delivering the volume of capital to absorb an outsize exit, and for generating liquidity for founders and the management team that brings it there.

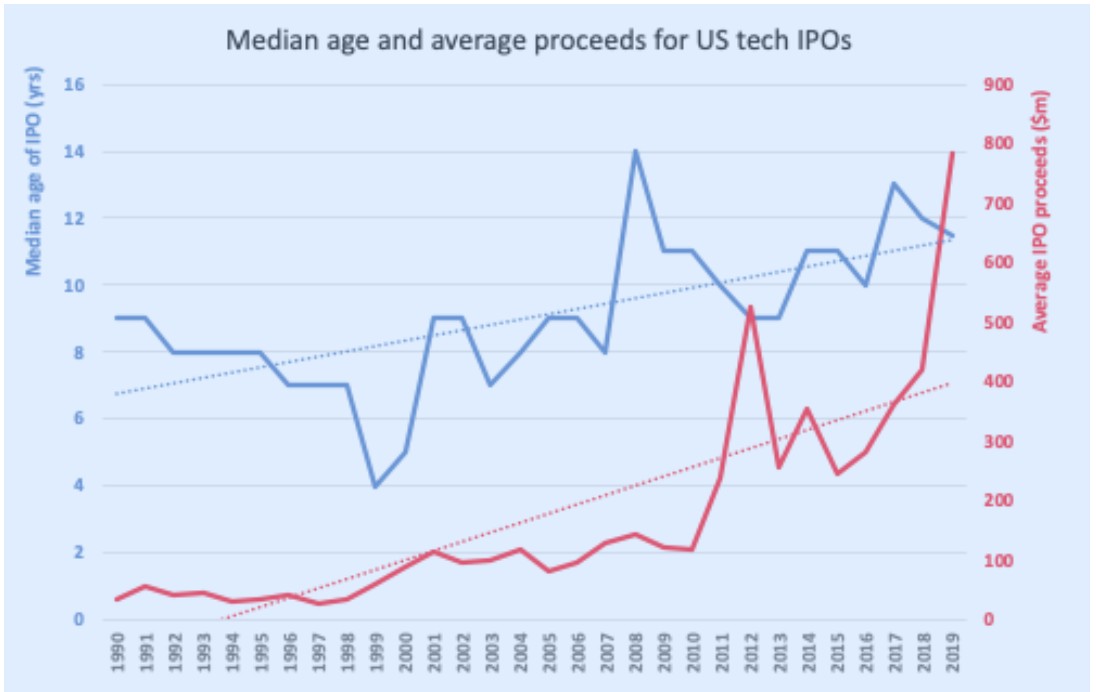

According to a well referenced study by Jay Ritter at the University of Florida[1], the time taken to get to IPO has been consistently increasing over the last two decades. The median age of US VC-backed technology companies coming to IPO in 2019 was over 11 years, up by more than a third since 2006 when the same companies were coming to market in just 8 years from inception. Perhaps not surprisingly this has led to a distinct drop in the number of tech company IPOs, down from a peak of 370 in the thick of the dot-com bubble in 1999, to just 34 in 2019, a level which has been sustained for much of the last decade.

As any entrepreneur would tell you, giving time for a company to grow is the best chance for demanding a higher valuation at the next fundraising point. Most private company funding discussions are therefore a balance between high cost growth, and extending “runway” (the time until a company runs out of capital to fund its expenses). In much the same way therefore, taking more time to move to IPO affords greater opportunity for a higher ticket exit; average US tech proceeds have risen eight-fold according to Ritter’s same study over the last decade (fig 1).

Fig 1. Companies remaining private longer deliver greater share of value pre IPO

Source: Initial Public Offerings: Median age of IPOs through 2019, Jay Ritter, University of Florida

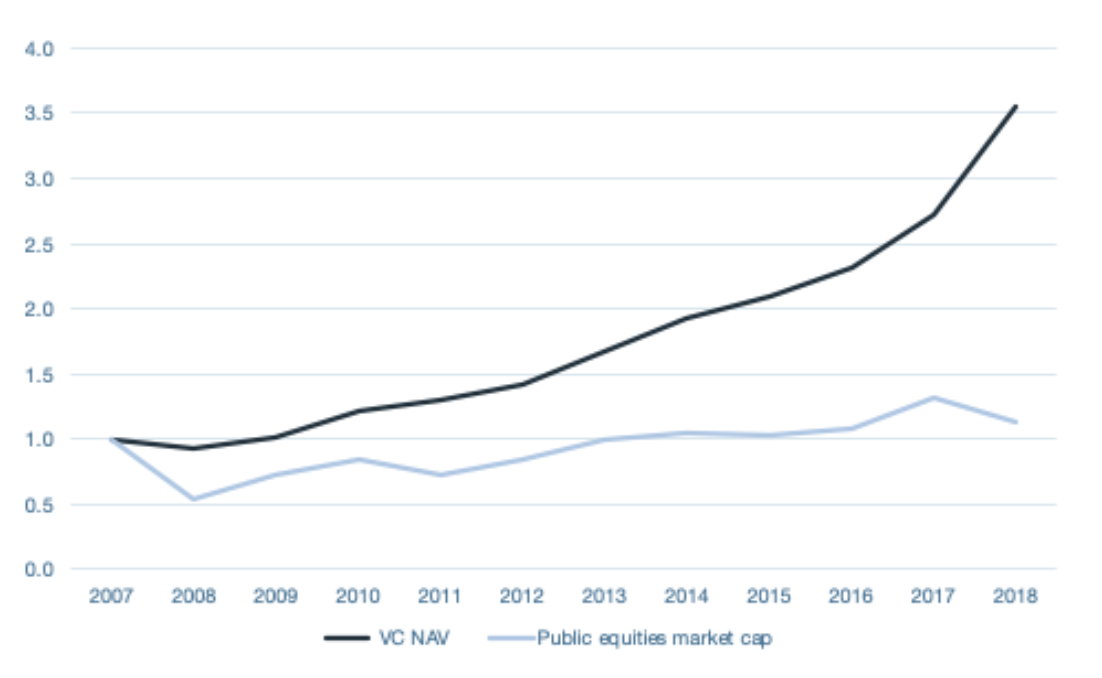

In a zero sum game this additional value captured by private investors must have come at the expense of post-IPO public markets, and both anecdotal and macro data supports this theory. US stocks that had an IPO in the first quarter of 2018 returned an average of 15% over the following one-year post-IPO period, less than half of the average of 34% and 39% returns in 2017 and 2016, respectively[2]. In turn, NAV based returns to private (venture) capital have significantly outperformed public markets by c 3x over the last decade (fig 2).

Fig 2. NAV based returns to private capital have outpaced public markets[3]

Source: Preqin Global Venture Capital Perspectives 2019; World Bank Dataset

Amassing unicorns

This is the dynamic that also explains the rise in both the US and in Europe of “unicorns” (privately held businesses with a valuation north of $1bn). Most of us will have seen the CB insights infographic charting an ever-more dense population of companies entering this club, particularly in the last 5+ years. This change is perhaps most stark in European Venture, where prior criticism was often that founders and investors sought early exits, leaving significant value on the table. However, in 2019 21 new unicorns from Europe joined Crunchbase’s unicorn listing, collectively adding $29.6bn in value and raising $7.5bn since 2000. McKinsey[4] measured similar trends in a report dated May 2016, noting the rise of privately backed software unicorns; of roughly 130 US $1bn value companies in 2010 only a small single digit percentage were privately held, yet by 2019 this proportion was above 40%.

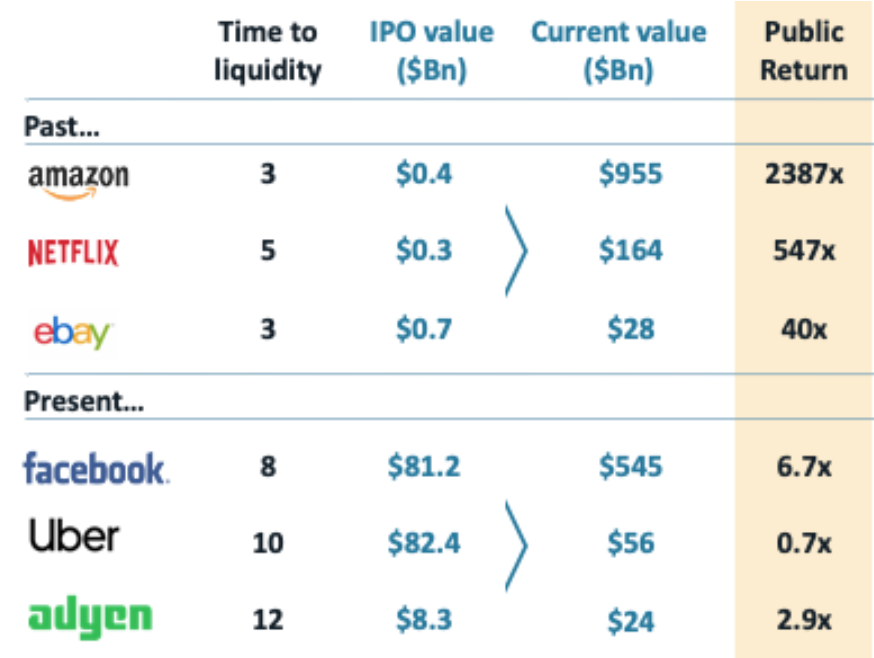

The dynamic has also often driven a dislocation between public and private market sentiment. From its peak in Nov 2015 to its trough in Feb 2016, the Nasdaq 100 fell more than 16%. Despite this turbulence in the public markets, this was an ebullient time for tech unicorns, doubling in their number during the course of 2015. In 2019 many IPOs suffered disappointing debuts, particularly WeWork around doubts over business models and pathways to profitability. Private company governance is largely predominated on driving growth and expansion, public company more associated with profitability and sustainability. These two models are often fraught at their intersection, particularly when a company is still yet to generate a profit at the time of its IPO (a trend that Ritter’s study again showed to be more prevalent in recent years).

Fig 3. The trend is towards the bulk of value being delivered prior to public exit

Source: Yahoo Finance

In a circular sense (both enabling and as a consequence of the performance of private later stage companies) there has been a significant growth of capital inflows to Venture Capital over the last decade, and a change in its composition. European Venture capital investment has doubled in the last 5 years from $15.3bn in 2015 to $34.3bn last year. Nearly 20% of this capital arrived last year in deals >$10m, in contrast to less than 10% only 5 years ago. In other words, growth is largely being powered by larger deals in later-stage companies, the life-blood for this “stay private” theme[5].

It remains to be seen whether these dislocations between public and private markets go further in the immediate COVID and post-COVID realities. With public markets spooked about the long-term market implications, we are seeing large price depressions in public markets, often in excess of 30% from their pre-COVID peaks. Some of this can be well understood. The IMF and the OBR are both assuming annualised hits to GDP in the high single digits, substantially recovering in 2021-22, meaning a real economy 5-6% smaller in two years’ time (2-3% pa growth that will be lost), perhaps therefore 10% in nominal terms. Adding an additional 1% to the equity risk premium due to heightened uncertainty would perhaps add another 10% reduction in prices, meaning that a 20% reduction in equity prices is explained by macro factors. Adding in the different (long-term oriented) growth lens of private capital, and sectors/companies where price depression has been in the 30-40%+ range, suggests that there is perhaps ample opportunity for increased “take-private” activity in the near-term future, particularly with many sources citing an estimated $0.5trn in private equity “dry powder” awaiting deployment.

Implications for fintech

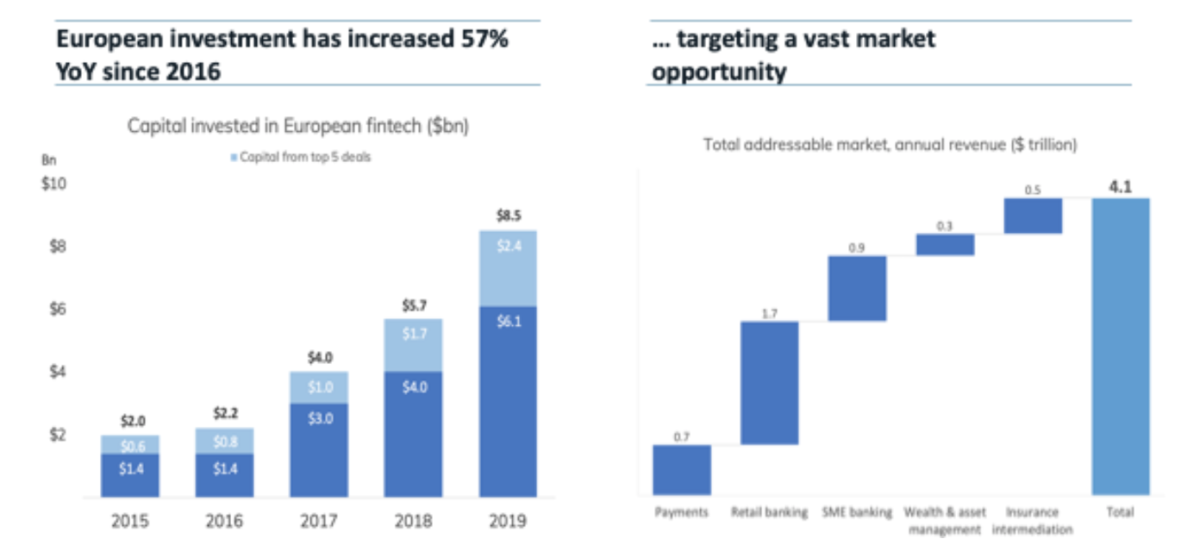

Sector wise, as we previously explained, much of the growth in European VC investment volumes has been in fintech, which has quadrupled in the last 5 years to $8.5bn in 2019. As a sector, the opportunity is relatively nascent compared to other verticals such as enterprise software and ecommerce given powerful incumbents, lack of convenient distribution and perceived barriers to entry. But advances in cloud computing and mobile distribution over the last decade has liberated the sector, opening incumbents to new waves of competition and paving the way towards unparalleled global market opportunity (fig 4).

In 2019 the top 5 deals in Europe accounted for over 25% of total capital deployed, including the $800m round in Greensill (London based supply chain finance company), $635m round in N26 (German based neo-bank), $269m in WeFox (German based insurtech) and $230m in Checkout (UK based payments company). Despite its latent emergence, businesses in this sector have grown rapidly and the capital needed to address the opportunities is evidently readily available in the private space.

Fig 4. Capital growth has been nowhere more apparent than in fintech

Sources: Innovate Finance 2019 FinTech Landscape, McKinsey Global Banking Annual Review 2018; McKinsey Beyond Banking 2019; McKinsey 2019 Global Insurance

Whilst it remains to be seen what the impact of the COVID crisis will have on capital inflows to venture capital in general and fintech specifically in 2020, in general these are early days for fintech and much of the expected upside is still to come suggesting that growth if anything will likely only be paused for later resumption in 2021 and beyond. Incumbents still dominate most sub-segments, perhaps most obviously in neo-banking where new entrants in the UK for example, account for substantially less than 15% market share despite their meteoric growth. Fintech is also perhaps better positioned than other sectors to ride out and indeed perhaps benefit from the uncertainty of a disrupted global economy – enhancing access to capital, scaling distribution through application of big-data, digitising previous physical relationships, and automating otherwise inefficient and labour-intensive processes.

Momentum has already clearly shifted as fintechs have fragmented customer relationships irrevocably with lower friction and generally better customer experiences. Despite their current domination therefore, the large incumbents have been slow to react to changing customer needs, are increasingly wary of the gains made by new entrants, and view acquisition as a viable means of innovation. Balance sheet capability is perhaps their last remaining strategic advantage, particularly when factoring in the actions of Big Tech who increasingly view the space as an attractive and (data) synergistic opportunity.

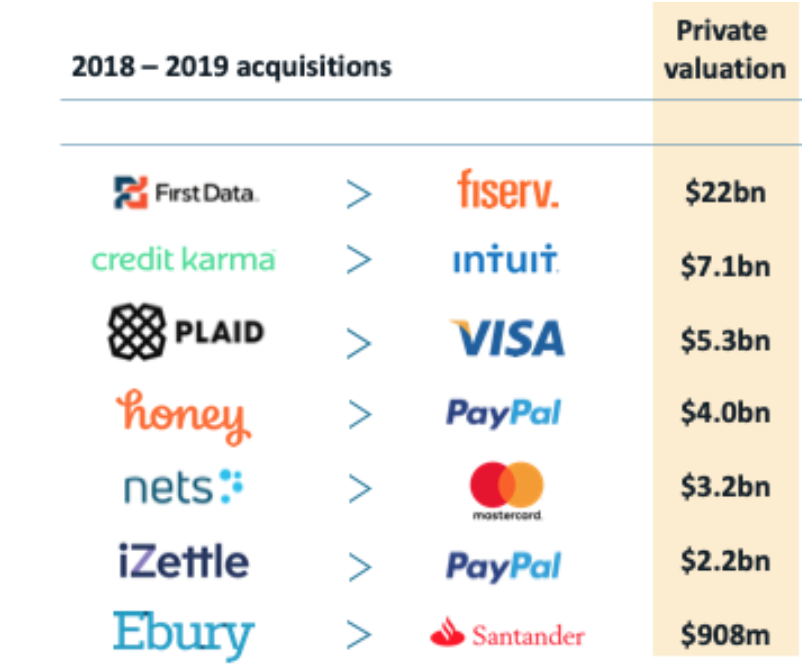

Strategic buyers with the added imperatives of cross-channel growth and offering cost synergies, have always been able to sustain higher valuations whilst maintaining share price accretion. For this reason we see many of the rising stars of fintech never reaching the public markets at all (fig 5). This is likely a dynamic that will be given further impetus in the short-medium term as the impacts of the C19 crisis leave a lasting legacy on the operation of public markets.

Fig 5. Many of the most valuable fintechs are never reaching the public markets at all

Source: Yahoo Finance

About Augmentum Fintech

Augmentum invests in fast growing fintech businesses that are disrupting the financial services sector. Augmentum is the UK’s only publicly listed investment company focusing on the fintech sector in the UK and wider Europe, having launched on the main market of the London Stock Exchange in 2018, giving businesses access to patient capital and support, unrestricted by conventional fund timelines and giving public markets investors access to a largely privately held investment sector during its main period of growth.

[1] Initial Public Offerings: Median age of IPOs through 2019, Jay Ritter, University of Florida

[2] Bloomberg, 16 April 2019. Average return for US IPOs over US $50 million issue size

[3] Realised and unrealised. Indexed to 2007; Net asset value (NAV) = AUM less dry powder. Total market cap. Global companies.

[4] “Grow fast or die slow: Why unicorns are staying private”, May 2016

[5] Pitchbook European Venture Report, 2019

Comments (0)