Why Iceland is Making a Mockery of the Eurozone

The financial crisis of 2007-2009 should be renamed the financial crisis of 2007-(?) when it comes to the Eurozone. Eight years after the peak of the crisis, the region is still drowning in debt, plagued by deflation, hobbled by a weak banking sector (headed by a big, fat central bank), and submerged in weak economic growth. While the Eurozone implodes, there is a small northern country, heavily criticised for its unorthodox way of dealing with a bankrupt banking sector, which seems to have overcome its crisis in just two years and is now flying high. While many in the UK and the Netherlands have good reason to distrust and complain against Iceland due to the Icesave case, the truth is that the country is a case study from which the Eurozone and the IMF should learn in order to avoid future mistakes when dealing with financial crises. Delivering an excellent performance without being overheated by central bank intervention, Iceland seems a great addition to an investment portfolio. The main Iceland equity indexes have been performing well and still have huge potential for the next few years as this small economy recovers at a must faster rate than any other country in Europe.

When central banks from major economies are unconstrained in the base money they are able to create, the best solution for smaller economies is not always to allow a free market to work. After all, quantitative easing and negative interest rates are certainly not the result of free market interactions, but rather of a planned distortion where central banks play a major role. When that happens, money flows tend to accelerate and increase in scale, inflating smaller economies all over the world until the point where it creates a financial crisis.

Unlike the rest of the world, when Iceland faced a bankrupt banking system, it decided the best way to deal with it would be to allow banks to go bust while jailing their executives. In the rest of Europe, policymakers adopted a different approach, as they preferred to pay huge benefits to the rotten bankers to get rid of them, while nationalising the debts they created. This of course solved the 2008 banking crisis, but at the expense of creating a bigger 2011 sovereign crisis, as peripheral Europe was by then unable to deal with the huge government imbalances created by the public bailouts.

In Iceland, the experience has been rather different, as the country, like Britain, always had its own currency. The government could never save a banking sector that was worth 10x its GDP, and it wouldn’t make sense to ask for international help to bail out a completely rotten system just to later come to the conclusion that the country would never been able to repay such loans. The only way out would be to allow banks to go bust, to save domestic deposits in the process, to ask for emergency funds and to impose capital controls to avoid a disorderly outflow of money. Unfortunately, capital controls are the only means a small economy like Iceland has to deal with situations like this, because the hot money flows that are the result of our fractional reserve system are so intense that the smallest sign of trouble can lead to a currency crisis and subsequent economic depression. Through the years we have witnessed many such episodes, whenever the initial capital inflows were at some point reverted.

The decision taken by Iceland certainly infuriated the UK and the Netherlands, many of whose citizens had savings tied up in high-yielding Icelandic online bank accounts. But these people are more accurately a victim of their own governments and central banks than of Icelandic banks, as the key factor behind the creation of such a bubble was the low interest rates that were maintained in these countries for long periods of time.

An alternative decision would have been for the government of Iceland to ask for help to save the banks and then to increase taxes on the Icelandic public. That was the route followed in the Eurozone, and it has been producing disastrous results. Ample proof of this outcome can be found in Greece. Eight years after the peak of the crisis (and many bailouts later) economic conditions continue to be chaotic, as the country lacks growth, experiences high unemployment levels and will never been able to repay even a small portion of the bailouts received. The decisions taken in the past allowed countries like Germany and France to gain time to avoid a bankruptcy of their own banking sectors, but that has been at the expense of the worst depression Greece has ever experienced. At the opposite extreme sits Iceland, which took a tough decision that steered the country through difficult times but, at the same time, created the conditions for a faster recovery.

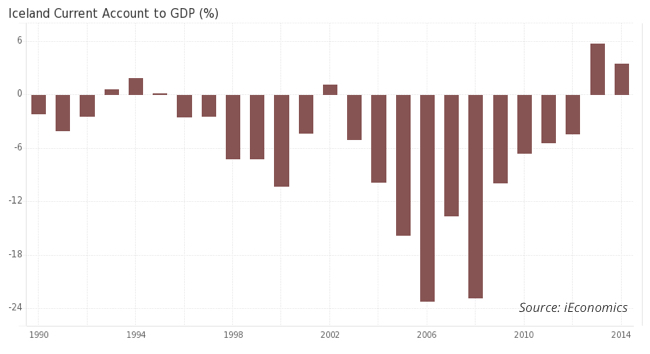

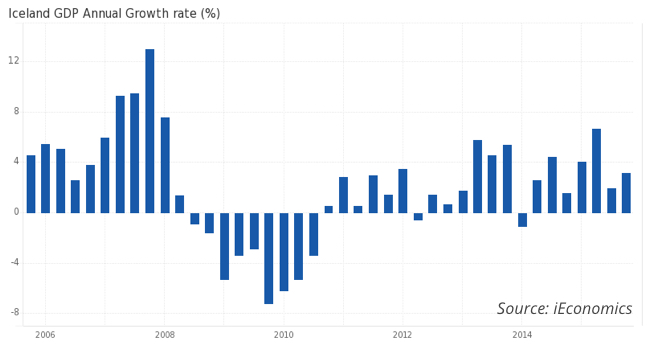

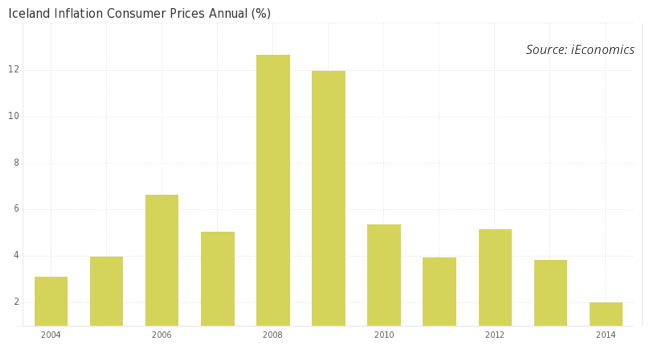

In 2008 Iceland suffered heavy losses. The equity market, for example, lost 95% of its value in just a few months. The economy experienced negative GDP growth rates between Q3 2008 and Q3 2010; the interest rate was hiked to 18%; the exchange rate between the euro and the krona rose from 83 in 2007 to 180 in 2009; inflation picked up above 12%; and over 60% of banks’ assets were written off. But in a country where the current account deficit amounted to more than 20% of GDP, the devaluation of the krona was more than necessary. The krona was trading at very high levels as the result of the exponential growth of the Icelandic banking sector, which had been competing for foreign deposits by paying higher interest rates than those on offer in the rest of Europe – with the side effect of ever greater current account deficits.

The devaluation of the krona completely changed the country’s economy: exports have risen, imports have decreased and tourism has doubled in size. The country has turned its deficit into a surplus and the krona has already started appreciating again, reflecting the improved economic.

Unlike what happened in the Eurozone (core and periphery), in Iceland the crisis was completely oversome. After nine consecutive quarters of negative growth, the country reverted to a healthy growth pace. The central bank expects the economy to grow 4% this year and another 4% in 2016, which is an enviable rate for a developed economy.

Instead of engaging in costly internal devaluations at time of severe economic weakness, the country opted for a mix of high interest rates and currency devaluations, which allowed for a much faster recovery. The unemployment rate hit 8.9% in November 2010 but then started decreasing to its current 3.7% level. In terms of government finances, the situation has also improved. Government debt to GDP has declined from 95% in 2011 to 75%, while it has also been able to repay its external loans and significantly reduce its external debt position.

In summary, it is undeniable that Iceland has been much more successful than Europe in dealing with the financial crisis. Instead of engaging in quantitative easing and negative interest rates, it allowed a bankrupted sector to be washed away, which accelerated the recovery. The higher interest rates incentivised domestic savings, and the devaluation of the krona just reflected the fundamentals of a huge current account deficit.

At this point, it is really difficult to find value in equity markets across the globe, as many prices are already inflated by central bank excesses. In the Eurozone equities have recovered faster than the real economy, but in Iceland it is the real economy that has been leading. Banks are ever more limited in money creation, as a new money system is being investigated for the country. Because of all this, I believe the OMX Iceland All-Share index is well undervalued and worth adding to an investor’s portfolio. While it has recovered from its lows, it is still trading at decimated values. With an expected 4.0% GDP growth rate for this year and the next, a healthy 2.5% inflation rate and an even better 3.4% unemployment rate, there’s little reason to look elsewhere in Europe. A way of getting exposure is through the Landsbref Equity ETF (LEQ), which is linked to the OMX Iceland 6 Cap Index. An alternative way is to purchase the Nasdaq OMX Iceland 8 Cap Index.

Comments (0)