Central Banks Have Lost the Inflation Link

For the last three decades, central banks have been concentrating their efforts on fighting two gaps – the output gap and the inflation gap – being mandated to throw everything they can at the economy in order to correct any major aberrations. While managing the first gap is the primary goal of government, managing the second is the core business of central banks. To succeed, they are equipped with independence and a myriad of instruments, ranging from benchmark interest rates to asset purchase programmes. All they need do is uncover the exact relationship between inflation and their available policy tools (in particular the benchmark interest rate) such that they can prescribe the right adjustments whenever necessary. But are they up to the task?

In a perfect world, one would find a linear relationship between inflation and interest rates (or the money supply). In such a world, one could depict a perfect relationship where inflation would decrease 1% for each x basis point increase in the key central bank rate. It would be relatively easy to apply policy. In an imperfect world, one would at least find a causality relationship between inflation and central bank action, even if that relationship may be subject to a few exogenous factors not under the control of the central bank. While a perfect prescription may be a fantasy, one would at least know that an increase in interest rates would lead to a decrease in inflation. The correct fine-tuning would be the major challenge for central banks.

However, in our rather imperfect world, it seems that central banks have completely lost the link between inflation and their policy instruments. Inflation no longer reacts to interest rate incentives, and several studies even challenge the traditional idea that low interest rates lead to higher investment and higher growth rates (and then higher inflation). The key central bank goal – to keep inflation near a certain target level – is one of the most puzzling phenomena faced today, and one which nobody seems able to explain or understand. The implication is that we have mandated central banks to do something they do not fully understand and of which they are in fact incapable.

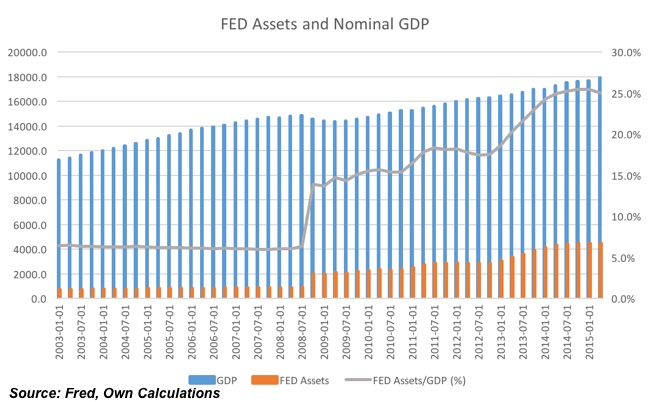

The total assets on the Federal Reserve balance sheet were kept below $1 trillion for most of the earlier 2000s, representing at that time around 6% of US nominal GDP. But then Bernanke’s thirst for experimenting with his own QE ideas combined with a lacklustre financial condition to double the FED’s assets in just one quarter (between the 3rd and 4th quarters of 2008). Consequently, the ratio of the FED’s assets to nominal GDP shot up to 13.9%. Additional increases in the balance sheet without accompanying rises in GDP led to further increases in the ratio to the current 25% level. The FED is now worth one quarter of the US economy. This happened because the perceived link between lower interest rates and higher investment didn’t materialise and thus the growth in GDP didn’t trail the growth in the FED’s balance sheet. At the same time, the ultra accommodative policy also failed to push inflation higher.

“Central banks are a mix of chance and magic”, as they have completely lost the link between their policy tools and the real economy. But “one can’t blame them, because there are so many variables in the process that aren’t under their control that keeping the value of money stable may only be achieved by chance or by magic”. If there’s someone to blame for it, it’s probably us for mandating them to do something they aren’t able to achieve.

Last weekend, policy officials and academics met at the 2015 Jackson Hole Economic Symposium to debate the main issues affecting monetary policy and the current state of knowledge. Several papers that were presented exposed the big gaps in knowledge we have and how far we are from understanding the dynamics behind inflation. Some of the presented papers go as far as to challenge some basic assumptions behind central bank intervention. For example, Simon Gilchrist & Egon Zakrajsek showed that companies hit by a financial crisis may raise prices instead of cutting them to hold on to their customers. Another paper by Gita Gopinah showed that as the dollar is widely used in international transactions, the US is not exposed to a great deal of currency risk, which mitigates deflation concerns that arise due to policy normalisation. (The other side of that coin is that countries like Turkey and other Emerging Markets may be severely exposed to inflation if the dollar continues rising.)

Several times in past articles I have argued that there is no reason to believe that the money supply and prices are linearly related. The notion that increases in the stock of money lead to increases in prices is good. The way we measure it is wrong to the point that only by chance or magic can we predict a relationship between the money supply and inflation. The quantitative theory developed by Fisher in 1911 stated that the total money spent on goods and services in an economy during a certain time-period must equal the value of the output changing hands, which is a trivial, unchallengeable relationship. But for the sake of simplicity we replaced total transactions with GDP and prices with CPI. The problem is that CPI ignores many products and services that effectively change hands during a certain time-period, with the biggest omission being financial assets, which account for more than half of our economy. When a central bank purchases assets on a large scale, it creates financial asset inflation, which isn’t captured by CPI and is largely ignored by central banks. But because central banks expect the rise in financial asset prices to increase wealth and lead to real asset increases, they keep on increasing the scale of their asset purchase programmes while CPI remains below target, largely ignoring any asset price bubbles they may be creating.

While CPI is a worthless measure for inflation, GDP is also a handicapped measure for total transactions, because it ignores transactions of previously produced assets (part of the GDP of a prior period). Additionally, we should not ignore the fact that money today is not well measured by M1, M2, or by any other monetary aggregate.

When measuring money we want to measure anything that is effectively used to purchase things. The central bank doesn’t control the money supply; it controls base money. With 97% of today’s money being created by commercial banks through credit, we need to look at credit as the best proxy for the money supply. Money created by the central bank may not buy things if commercial banks park it as unused reserves. Only when commercial banks expand their balance sheet does the “real” money supply increase. With banks slashing credit for the real economy, it should be no surprise that CPI remains low. For the economy to grow and inflation (as measured by CPI) to increase, banks must supply credit for real investment and consumption. But banks took the opportunity given by the central bank asset purchases to refinance themselves instead of using it to expand credit. Under such a scenario, why would one expect consumer prices to rise? It would be much better if the central banks directly purchased bad assets from banks or if they imposed new rules favouring the creation of credit for investment purposes. What Bernanke put in place was the dynamics for the creation of the biggest asset bubble in US history just a few years after the prior one.

After many years of distortions, we are at a junction where there is an urge to start normalising policy, but central banks are worried about the effects the policy normalisation may have in the economy, fearing another liquidity squeeze and a market Armageddon. But with the latest 2nd quarter GDP preliminary estimate coming at a healthy 3.7% annual rate, it is becoming ever more difficult to justify the current policy stance, in particular because it leaves no room for further easing in the near future in case it is needed.

As Narayan Kocherlakota, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis puts it: “I look at Japan, Europe, U.K, the Canadians, you just see that more and more countries are getting close to their effective lower bounds… This is the challenge facing central banks, which is that aggregate demand is low, and we’re up against the boundaries of the policy space.”

Central banks know less than they pretend to know and have been ignoring almost all risks that are associated with their excessive policy stance. They undershot inflation, they overshot the real money supply, and they then presided over an epic decline in the velocity of money, which is nothing more that the aggregation of all their errors. In the future to come we are going to experience massive turbulence, as central banks create boom and bust. On one hand, we have the central banks trying to normalise policy; on the other, we have massive bubbles waiting to be pricked. Will Janet Yellen prick them in September and be remembered as the mother of the next crash? I believe she won’t. In fact, she will probably postpone it to next year.

Comments (0)