A New Monetary System for Greece

As seen in this month’s Master Investor Magazine

“The financial crisis of 2007/08 occurred because we failed to constrain the private financial system’s creation of private credit and money”

– Lord Adair Turner (former Chairman of the now extinct UK Financial Services Authority)

The Greek Misbehaviour

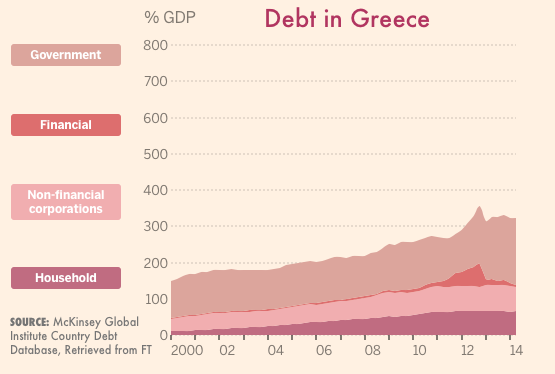

Over the course of many years, and while the global economy was growing, no one really cared about the growing imbalances that Greece was showing. Debt grew to the unsustainable levels seen in 2010, which required the intervention of external entities to help avoid a financial collapse in the country. Exactly five years ago, the Eurozone, the IMF, and the ECB agreed a €110 billion bailout package for Greece to avoid the country’s default. One year after, a second bailout worth €130 billion was approved while at the same time they forced private bondholders to accept a 53.5% loss on the face value of Greek government bonds. Another round of €8.2 billion was later approved. Accompanying the bailout money, several austere measures aimed at reducing the country’s debt were also adopted by successive governments, but all they achieved was to convert financial turmoil into economic chaos, completely sinking the Greek economy.

The Greek effort over the last five years has been admirable, I would say. They were able to turn a huge government deficit into a tiny one, which is now inside the 3% limit required by the EU treaties. So far, so good. But the enthusiasm stops when we look at what happened to GDP. Between 2009 and 2014, real GDP grew at an annual pace of -4.9%. With the denominator declining at such a high pace, the debt-to-GDP ratio is increasing and the country’s financial position is looking ever more unsustainable. The “troika” of creditors would say the Greek misbehaved and their effort was not enough. They would additionally argue that Greece needs to implement even more austere measures. Others, in line with Paul Krugman’s thinking, would attribute full blame to the austerity itself, claiming that public contraction just leads to a great economic depression and to solve it Greece should have adopted even more fiscal indiscipline. Which one is right? Should we blame Greece for indiscipline or allow them to further expand public spending to boost GDP growth?

Greek Debt vs. Global Debt

A few weeks ago, McKinsey & Co. conducted a study on global debt that shows growing imbalances around the world, as indebted countries have not been able to improve their financial soundness. Debt is increasing much faster than GDP since the first signs of financial turmoil in 2007, even though several measures were adopted in order to deleverage. Debt is not a Greek problem but rather a global problem. We very well know that the UK, the US and Japan (just to name a few big names) all have unsound public finances. The main reason why they can sustain them for longer than Greece is because all of them retain sovereignty over monetary policy.

Interestingly, the same study shows a path of change in global indebtedness. Some countries that went through the 2007 crisis without suffering much from it, as is the case with Australia, the Netherlands, South Korea and Sweden, are now showing worrying growth in household debt, in particular mortgage-related debt. Why is that?

I have several times mentioned the Kindleberger’s book “Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises”. Allow me to make another reference to it, as the book (written in 1978) is so prescient that it suffered several updates prior to its current sixth edition published in 2011 to absorb the latest data. Kindleberger notes that we have been heading from crisis to crisis, with the problem of one country at a certain time being exported to another region at a later time. Starting with the growth in bank loans to governments and government-owned firms in Mexico and a few other developing countries, the wave created a later credit bubble in Japan. As policymakers tried to prick the bubble, it moved on to other Asian countries and led to the Asian financial crisis of 1997. Then a new wave was formed in the technology sector and a new one in real estate at the beginning of this century. It always starts with a large pool of money that can be easily accessed to provide loans, waiting for some positive shock with the ability to create the enthusiasm that leads to credit expansion, asset price rises, and further enthusiasm. Then a self-serviced price loop is created which leads to the excessive leverage we often see and a subsequent bubble burst followed by economic depression.

As long as there is credit waiting to be created, we are able to move from bubble to bubble.

McKinsey’s Solution

The report from McKinsey expects global growth to remain sluggish and as a result debt-to-GDP ratios to increase. To solve the problem they propose:

– Better risk sharing between borrowers and creditors. For example, companies should rely more on bond and capital markets instead of bank loans. Mortgages to households should vary according to the household’s specific circumstances.

– Sovereign debt should be restructured. As debt continues to grow, it should be recognised that the situation is unsustainable and that a hair cut is needed. They propose the central bank should keep the bonds and accept the loss (even though this is forbidden in the EU by its treaties).

While McKinsey has the courage to state what we all know but still fail to admit – which is that the current global debt levels are neither sustainable nor workable – it still fails to recognise what Kindleberger very well reports in the aforementioned book: the expansion of credit is at the heart of the problem.

In terms of the improved risk sharing McKinsey claims to be necessary, I believe it all starts with removing the state guarantee on bank deposits. That is the most important step towards removing the moral hazard problem that leads banks to externalise risk to society as a whole. One of the main problems that led to the past mortgage crisis was the fact banks were no longer worried with the credit quality of the borrowers as they were re-selling the mortgages as securities. When that happens the bank approves as much credit as possible as the bank receives a commission that is independent of the borrower’s payments, because the loan is no longer on its books. Transposing the problem to the state guarantee, when there is such a pledge depositors no longer care for the soundness of the banks and only seek for the best interest rates. On the other hand we have banks that compete with each other to offer the best rate to depositors and capture their money, as they don’t bear the full cost of it, because they know the government would bail them out if needed. If there were no state guarantee, risk perceptions would improve and the risk taken by banks would decrease substantially or translate into higher interest rates paid on deposits.

But, the abolition of the state guarantee is not enough. Why? Because our monetary system is based on fractional reserves, under which there’s not enough money to repay depositors if even only a small part of them wished to withdraw their cash. Coins and notes make for roughly 9% of the total stock of money, which means that most deposits are backed by thin air. At the first sign of smoke, bank runs would occur and the payments system would be at stake. Governments can’t allow this because if a bank run occurs and a bank fails, many other banks can be dragged down too. In the end chaos would set in. So, I must conclude that the fractional reserve system requires a state guarantee.

With the wrong risk sharing that results from distorted risk perceptions (as the state must give guarantees to depositors), banks engage in a credit spree when they want too. The central bank creates electronically issued reserve money and sets the reserve requirement ratio. Then banks wait for deposits from clients, keeping a fraction to comply with the reserve requirement and lending the remainder. Then again, part of it will remain in the bank as deposits, enabling further lending. So, if the reserve requirement is 20, the absolute maximum the high street banks can expand on base money is 5 times.

The above is only correct in textbooks but absolutely wrong in practice. The BoE, the ECB and the Federal Reserve (and most other central banks) no longer have any control over the money supply. The reserve requirement is an entertainment measure that serves for absolutely nothing and it is never a limit on credit expansion for high street banks. Banks lend whenever they please, which creates deposits. They only afterwards look for the reserves they need, which are provided by central banks as and when necessary. For deposits to exist there must also be someone in debt. Under such a system, debt is the engine and one just can’t blame a country for accumulating too much of it. The guilt lies not with the government, companies, or households but rather with the monetary system. To solve the problem we need to change the system.

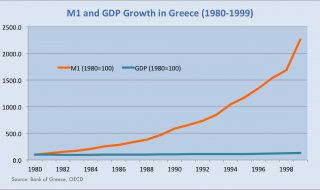

The chart bellow shows the expansion of both M1 (notes in circulation plus demand deposits) and GDP for Greece in the period pre-Euro between 1980 and 1999. As you can easily spot, the growth of the money stock has largely surpassed the growth in the country’s wealth.

M1 grew at an annual pace of 17.8% in that period while GDP only a modest 1.4%. Given the current monetary system, under which deposits are created after credit is awarded to someone, the rise in the country’s debt could only be disastrous. The main reason is the power given to high street banks to create money at will, while failing to align their interest with society’s.

Even after entering the monetary union, M1 continued growing at 6.6% between 2000 and 2009 while GDP grew at 2.6% per year. Only after 2009 did financial disaster lead to a reduction in M1, which resulted in a severe crisis in the country without allowing it to reduce debt.

Towards a New System

The old view that banks need some people to save money in order to be able to lend is plain wrong. Our fractional system just doesn’t need any savings to be able to lend.

In a speech at Southampton University in 2011, Adair Turner, head of the Financial Services Authority at that time, said the following:

“Banks it is often said take deposits from savers (for instance households) and lend it to borrowers (for instance businesses) with the quality of this credit allocation process a key driver of allocative efficiency within the economy. But in fact they don’t just allocate pre-existing savings, collectively they create both credit and the deposit money, which appears to finance that credit. Banks create credit and money.”

So, it seems possible to create future wealth without saving any part of present wealth. That doesn’t sound right. But let’s say it is possible. Then banks would lend the money for capacity creation. As a result GDP would grow with M1. But look at our economies. Productivity has been growing at less than 1% per year. The largest part of the credit extended by banks is not for investment activities but rather to buy pre-existing assets, including real estate, and for speculative activities like buying financial assets. Our legislation, under Basel rules, makes this even worse as it favours collateralised loans, which is never conducive to investment.

As you can guess, banks expand credit when they are more confident. The largest part of it goes toward real estate and the equity market. GDP doesn’t grow much because these activities don’t generate wealth, but asset prices rise, which in turn generates more demand for credit and further price rises. This creates a disconnection of asset prices from fundamental values. At some point, a crash occurs and we return to the same. High street banks enhance the boom-bust cycle and it is not possible to grow without debt creation.

The alternative is to separate money creation from the lending activities of banks. That is to say, let the central bank regain the power to create money while allowing banks to allocate savings at their will but without generating the current boom-bust. The idea is not new, having been first developed soon after the Great Depression in the 1930s and known at that time as The Chicago Plan. More recently the plan has been revisited by the likes of Ben Dyson and Andrew Jackson in “Modernising Money: Why Our Monetary System Is Broken And How It Can Be Fixed” and by F. Sigurjonsson in a report commissioned by the Prime Minister of Iceland and entitled “Monetary Reform: A Better Monetary System For Iceland”.

The idea is to limit the action of commercial banks by creating two account types: (1) Transaction Accounts, which are held at the central bank and are risk-free and thus pay no interest at all; and (2) Investment Accounts, which are held at commercial banks and have some varying risk and thus pay interest. Banks can no longer create money. They still have the clients that deposit their money in risk-free accounts (Transaction Accounts), but these accounts are effectively held at the central bank, even if managed by the commercial bank. This means that in case of a bank default this money is fully protected. But banks can still offer time deposits with varying maturities and risk. Clients may opt to transfer their money from the risk-free demand deposits (Transaction Accounts) to these time deposits (Investment Accounts).

Under such settings there are two significant changes relative to the current system. Firstly, before using the money from clients to invest, the bank must capture the savings from clients. Secondly, the client needs to monitor bank activities to some degree as these investment accounts do have risk. In such a system, there is no risk of too much credit creation.

But, there’s still a missing link – the money creation process. The central bank must create money in a sound way. A committee needs to be created in order to decide on how much base money is going to be created. Eventually, money creation can be tied to GDP growth but there are other options as well. The exact configuration must be debated. In any case money is now a central bank asset that still needs to be allocated. The proposal made by Sigurjonsson and Dyson & Jackson goes in the direction of this money being given to the government, which in a democratised way would then decide what exactly to do with it. It could be used to reduce taxes or to invest in some infrastructure investment projects, for example. As a result, money creation would be under control and much more democratic.

Nevertheless, the incentives to create more money than needed to keep the economy oiled are too strong and inflation could be generated. The system would have to be very tight to avoid being exposed to the political cycle. But in any case, the problem of attributing too much credit would be completely solved.

Unlike the Icelandic case, Greece has an excellent opportunity to get rid of a system that is keeping it zombified for decades. The Eurozone would never agree to cut Greek debt by the necessary amounts for Greece to have a new start, and even if it does, as long as banks keep credit creation under their umbrella, they will move towards the exact same problem in just a matter of years. Allowing a default now is their best chance at starting over from scratch. They can implement a new sovereign based drachma, fully controlled by the central bank. Even if the exchange rate fell at first, it would be a one time, temporary effect. With tight rules regarding money expansion, there’s no reason for the currency to revalue over time, in particular when all other banks are using money printing extensively and well above their respective countries’ growth rates. The beauty of this is that the central bank would lose control of interest rates, which finally would be determined in the market and thus become an efficient allocation price leading to correct investment decisions.

Comments (0)