Inequality: Causes and Solutions

The latest data published by Oxfam show a worrying increase in income inequality during just the last few years. Many believe this to be the consequence of the free market, and in response raise arguments in favour of policy intervention. I myself believe public intervention to be the cause, not the solution, as the global economy currently takes its cue from central planning rather than from free markets.

The data presented by Oxfam show that the world’s 62 richest people hold as much wealth as the bottom 3.5 billion, whereas the ratio was 388:3.5 billion back in 2008. Put another way, 62 people have as much wealth as half of the world’s population. Additionally, Oxfam found that the top 1% controls more wealth than the other 99% of the population. Such numbers raise concerns about the route that wealth distribution is taking, and remind us that in addition to boosting total wealth, we also need to look at its distribution.

At first glance the data seem extreme. How is it possible that 62 people can account for half of the world’s wealth? Surely governments should have taken action to address such extreme inequality.

Through public intervention, governments could raise taxes on the richest and increase transfer payments to the poorest. They could even guarantee an income to every citizen! Why not simply blame free market forces for the unfairness of the final outcomes and allow government to take care of the problem through public policy?

However, after a second look, the inequality issue seems much more complicated than that. Do we really want to eradicate it? Would it be fair? Would the outcome be better? Let’s look at a very simple example. Louis and Sam are brothers who decide to take very different approaches to work. While Louis spends 10 hours per day working, Sam prefers spending just 4 hours. At the end of the day, Louis brings home £300, while Sam picks up just £120. Income inequality then arises. Is it unfair? Should the government do something?

Let’s say the government wants to eliminate the income inequality by taxing £90 from Louis’ income and giving it back to Sam. At the end of the day both would come home with £210. Inequality would have been eliminated… but so would fairness. The next day Louis finds that working 4 hours provides him with the same income as working 10 hours. All adjustments done, both would work 4 hours and bring home £120. The economy would shrink.

While being simplistic, the above example helps us to understand why inequality is sometimes the engine of economic growth. It is the free market reward to effort and risk that acts as an incentive for progress and innovation. When we remove the market reward, the incentive for people to stand out from the crowd ceases to exist, and no one sees any advantage in doing so. The economy would then shrink, as in the example above. Without the reward, people like Henry Ford, Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Alexander Fleming would have never existed and I would probably be dead by now or, if still alive, I would most likely be writing this article by hand to send it via Royal Mail for you to read it in a few days’ time. Some degree of inequality may be necessary for the world to be a fair place and for progress to occur.

But, inequality isn’t always the result of innovation. It sometimes comes as an undesirable and unfair redistribution of wealth and income. Under such circumstances, some kind of intervention could arguably be desirable in both economic and social terms, in order to redistribute the wealth more wisely. One example is when inequality is inherited. In that case inequality generates more inequality without being related to any kind of innovation. When that happens the government may see it as intolerable and may wish to act to reduce it.

Governments have in general attempted to close the inequality gap by taxing the richest and redistributing wealth to the poorest. At the international level, differences in wealth between developed countries and emerging or under-developed countries have always been in the spotlight. But recent studies have been showing that differences between countries are decreasing. What has been increasing is the wealth gap within developed countries, which points to shortcomings in public policy.

The fractional reserve system – under which banks must only retain a fraction of their deposits as reserves and have their reserves guaranteed by the central bank – just doesn’t work for the majority of the population. When the economy is growing and sentiment is buoyant, banks just relax their lending criteria and advance loans in excessive amounts. A good example of this is Iceland during the period that culminated with the 2008-2011 financial crisis. At the end of the second quarter of 2008, the three largest Icelandic banks had accumulated 14.437 trillion krónur in assets, equal to more than 11 times the country’s GDP. Of course, when leverage is that high it just takes a small deceleration in prices for a liquidity squeeze to occur. By then, the government would be faced with two possible solutions: (1) allow the banking system to collapse, making banks liable for the excessive risks taken in the past while at the same time allowing an economic contraction to unfold; or (2) bail out the banks to avoid an unorderly default and its consequences for the real economy, but in the process making the whole population liable for the bank’s past excesses.

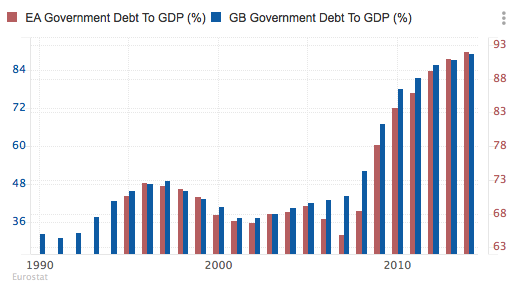

In Europe the preferred option has often been the second. In the process that followed Europe’s financial crisis, banks’ balance sheets were cleaned up while governments’ balance sheets turned sour. We could say that many peripheral governments already held large debts, but attributing the sovereign crisis to past excesses is naive. These governments had been forced to bail their banks and unload the losses on the entire population. The result was a quick accumulation of debts that rose to gigantic levels and which are still out of control. We could say that solution 1 would be much worse; but we could also argue that solution 2 is only better because of an ill-conceived system. If we allowed banks to operate in a free market from the very beginning, they would never have created as much credit as they did, because they would go bust well before they could do it. In the end we would not need to save banks at the expense of the whole population.

A severe problem with solution 2 is that it leads to inequality. The EU forced peripheral countries to bail out banks while imposing severe limitations on public finances thereafter. If we think of public finances as a redistribution tool, in limiting deficits we are limiting such redistribution. Governments cut transfers and any existing social programmes while they increased taxes on the middle classes. In the end, they created a policy that increased income inequality, for the sake of bailing out banks that took too much risk because they knew they would be bailed out from the very beginning. This entails a massive transfer of public money to private interests and benefits all those that once gambled with the whole population’s wealth by creating money out of thin air – a reward for failure.

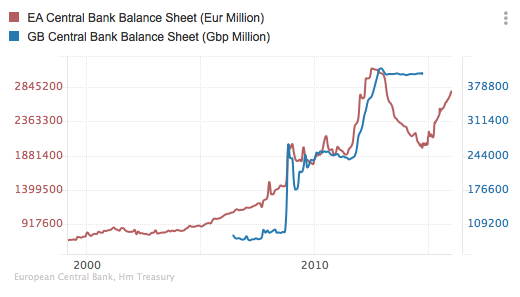

But the story doesn’t end here. Sitting astride the entire banking system are the central banks, which have been unable to keep the banking system under control and have arguably contributed to the boom-bust cycle. In fact, through keeping rates too low for too long while purchasing assets, the central bank has helped to increase the wealth of those holding the bulk of real assets (i.e. the wealthy). Of course, Ben Bernanke would claim that QE is good for the poor because it decreases unemployment, benefits debtors, and increases the price of houses. That may be true, but we should never forget that QE targets financial assets, which are a significant part of high income households’ wealth. At a conference in 2014, Yves Mersch, member of the executive board of the ECB, admitted:

“There is no clear evidence whether standard monetary policy has a dampening or intensifying effect on economic inequality. Non-conventional monetary policy however, in particular large scale asset purchases, seem to widen income inequality, although this is challenging to quantify.”

At the same time we should never forget that through driving asset prices above fundamentals, non-conventional monetary policy lays the foundations of the next financial crisis where jobs will be lost. Then comes Bernanke’s argument that QE improves the job market…

Central banks and governments are becoming ever larger…

Inequality is a sensitive matter that is hard to tackle – particularly when we have governments, who are purportedly in place to reduce it, helping to increase it. The first step lies in redefining the current banking system, which is highly susceptible to boom and bust. The next step is to limit central bank action. Instead of justifying central bank intervention as being a lesser evil, it is time to work on the causes that lead the economy towards that crossroads.

Comments (0)