How to Invest Like… Benjamin Graham

As seen in the April issue of Master Investor Magaizine

“People who invest make money for themselves; people who speculate make money for their brokers.”

― Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor

Are You an Investor?

Investment, speculation and gambling reflect three different approaches towards the equity market that often end with a similar outcome: the enrichment of the broker that makes all the trading involved possible. No matter how a trader positions himself in the market, he often ends up placing random trades, following the crowd, being too concerned with short-term price volatility, trading on others’ advice, failing to diversify sufficiently, knowing nothing about the real businesses behind his paper trades, being passive regarding his ownership, and getting seduced by others’ optimism and scared away by others’ pessimism.

But, according to Benjamin Graham, “an investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return”.

Most activity fails to meet these simple criteria and is in fact just speculative. Additionally, Benjamin Graham believes that investing is a solitary activity that involves profound research and deep patience; one that involves buying from pessimists and selling to optimists; one that involves disregarding the trend-following market consensus and replacing it with realistic historical value and real capability. In this inaugural instalment of our new feature, “How to Invest Like…”, we are going to travel back in time to meet the father of value investing, Benjamin Graham.

The Father of Value Investing

When the concept of value investing comes to mind, the first name that pops up is Warren Buffett and his immortal buy-and-hold strategy. But, while Buffett should be praised for his own investment success that led him to a personal net worth near £50 billion, the chief credit should be attributed to the most influential man in his investment career, Benjamin Graham. The British-born economist, professional investor and academic was so influential in Buffett’s life that Buffett named one of his sons Howard Graham Buffett in honour of his mentor.

Born in London, Benjamin Graham moved to New York City when he was just one year old. He graduated from Columbia University with distinction at the age of 20 and landed a job on Wall Street. In 1928 he began teaching at the Columbia Business School, during which time he came to be known, along with David Dodd, as one of the most influential figures in value investing.

At the time when Graham started out, trading was mainly speculative and/or based on insider information. But Graham believed that true value could be unlocked through deep research and analysis of a company’s statements. Over the years he set about improving his knowledge and taught many Wall Street professionals and Columbia students on the subject of value investing.

Examples of Graham’s disciples are Warren Buffett, John Templeton and Irving Kahn. In 1934, Graham and Dodd wrote one of the most influential books (and the first) about value investing, “Security Analysis”. Together with “The Intelligent Investor”, published in 1949, these books laid the foundations for the concept of value investing. Many today still follow the original ideas advanced at that time. A good example is David Dreman (MI Magazine, issue 8, November 2015, p. 90-93) and the activist investor David Einhorn.

“The Northern Pipeline Affair”

One of the central features of Graham’s investment attitude was the way that he viewed stock ownership. He believed that, more than anything, a share represents an ownership stake in a real business, which entitles the shareholder to receive part of the accumulated profits in the form of dividends. Because of this, he always gave priority to equities with a history of uninterrupted dividend payments. If a company is making money, why not increase cash disbursements to shareholders? This is particularly sensitive in cases where a company is accumulating profits and retaining them as cash and short-term investments, rather than using them in operating activities to expand its profitability. While Graham’s reasoning about cash disbursements makes sense, the observation of the real world shows that management often prefers to retain the extra earnings, instead of paying them out to investors. This behaviour resembles an episode in Graham’s investment life that became known as “The Northern Pipeline Affair”.

Northern Pipeline was a company that resulted from a split of Standard Oil (owned by John D. Rockefeller) into several smaller companies. After digging into Northern Pipeline’s financial statements, Graham found that the company held $95 per share in liquid assets (including railroad bonds), while its stock was trading at just $65. If the company opted to disburse all its cash and cash equivalents to shareholders, its shares would at least be valued at $95 – a value that wouldn’t include the rest of the company’s assets, let alone its business as a going concern. Such a massive undervaluation convinced Graham to amass a significant position in the company’s stock, expecting that sooner or later management would pay out the cash in the form of a huge dividend.

As the money was not invested in the company’s core business there was a good reason for management to disburse it to shareholders. But for that to happen, Graham had to put a lot of effort into persuading them to do so. He then learned an important lesson: persuasion is often not enough to stir management to action.

It sometimes requires a more activist stance, which includes convincing other shareholders to support the cause, accumulating enough voting proxies to be elected to the board, and finally putting management between a rock and a hard place. That was exactly what Graham did in 1927: he convinced other shareholders to back him; he was then elected to the board, and finally forced management to distribute an amount of $70 per share.

The episode became know as “The Northern Pipeline Affair” and has been one of the most important investment lessons, which even led to the creation of a special category of hedge funds known as activists. The main idea backing the concept of activism is the fact that a paper ownership also represents a real ownership that entitles its owner to voting rights and to participate in corporate decisions. Investors may use their rights to force companies into taking action, in particular when management action seems unreasonable. David Einhorn’s Green Capital is an example of an activist investor/hedge fund. Einhorn and his hedge fund have often accomplished corporate changes through proxy votes they managed to secure. Recently they have been trying to force Apple to distribute part of its accumulated cash pile to shareholders. They managed to achieve a partial success, as Apple has been gradually increasing its disbursements. Einhorn’s actions are rooted in those taken by Graham almost one century ago.

Investment Style

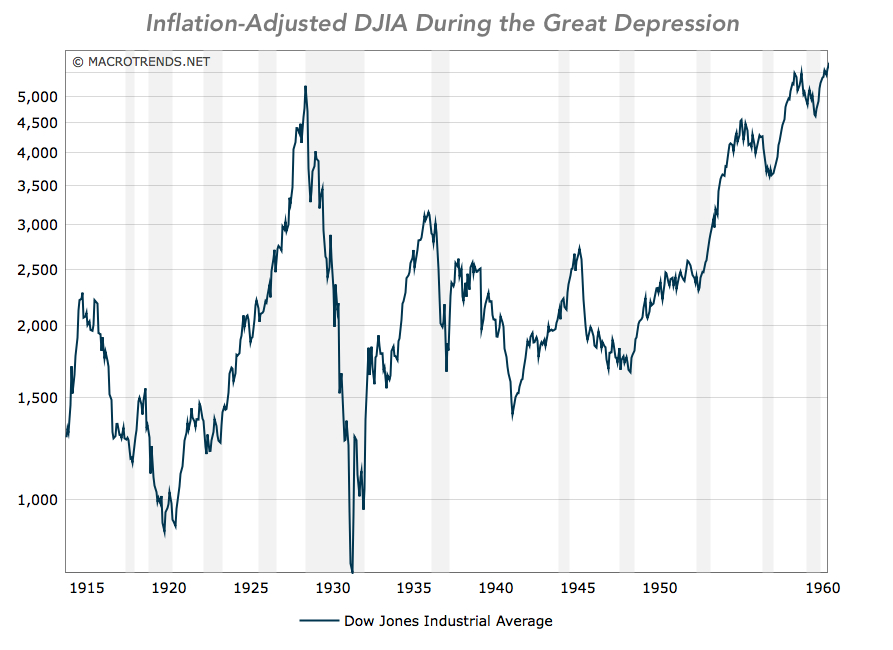

In the book Graham wrote together with Dodd – “Security Analysis” – they laid the foundations for what later became known as value investing. Published in 1934, the book benefited from the observation of what happened during the Great Depression. On September 3, 1929 the Dow peaked at 381.17 after increasing in value tenfold. On October 29 of the same year, less than two months later, the industrial average closed at 230.07, or 40% below its peak. Later, on July 8, 1932, it had accumulated a peak-to-trough loss of around 89%.

Such massive volatility taught Graham two important lessons that he incorporated into his investment strategies: 1) the market is not always rational; and 2) any value investment should focus on the long term.

The short-term irrationality was so important for Graham that he created an allegory with the personification of the stock market into Mr. Market, an individual that one day is willing to buy his partner’s share of the business for much more than his partner believes his share to be worth, while the next day being so pessimistic that he is willing to sell his stake for much less than fair value. The allegory resembles the irrational short-term behaviour that drives equity prices, often boosted by optimism and depressed by pessimism. This led to an additional lesson that Graham incorporated into his investment style: 3) psychology plays an important role in the market, as investors will tend to overreact to any kind of news, exacerbating short-term movements and leading to what today is known as positive feedback loops. In his later book, “The Intelligent Investor”, Graham’s sensitivity to market psychology is well perceived when he claims “the Intelligent Investor is a realist who sells to optimists and buys from pessimists.”

If there is something really different in Graham’s investment attitude relative to his contemporaries it is his scientific roots. He turned value investing into an academic discipline because he believed an investor could beat the market by digging deeply into a company’s financial statements.

According to Graham, if there is value to be unlocked it is in finding undervalued companies which others ignore. Investors should focus on company statements and reality and not on what they hear from others. “The stock investor is neither right nor wrong because others agreed or disagreed with him; he is right because his facts and analysis are right.” From this, another key commandment was born: 4) look at fundamentals… nothing more. And speaking of what others do, what they do as a group gives rise to what is known as the market consensus, which is already incorporated into prices, reflecting what is known. What drives price changes is what is not known. In this vein, the Intelligent Investor should buy something others won’t, without fearing the unknown, as nobody can tell the future. The intelligent investor (5) shall not move with the herd.

The herd is a victim of market psychology, which overreacts to information. Companies with exceptional profits are often backed by investors, while companies with lower profitability are sold on. But Graham argues that exceptionally high profits cannot last forever, as these profits would attract other companies into the industry and eventually drive profits lower. The same reasoning could be applied to below-average profits. This leads to one important market feature: 6) share prices suffer from mean reversion. In general, analysts fail miserably to predict future profits as they focus too much on the latest earnings release. In the long term a company is constrained by its real capability, and therefore looking at its historical values and significant present developments is a better focus for investors than just looking at the latest numbers. When these numbers are way above or below historical numbers, they usually lead to huge movements in price that just represent a good long-term opportunity in a contrarian direction.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, for Graham, the distinction between an investor and a speculator is very important and relies substantially in the protection of principal. As Warren Buffett puts it: just “don’t lose money”. Investors should seek out a margin of safety that acts as a defensive buffer in case things go the wrong way. An investor should look at companies with a few characteristics that help mitigate risk and improve returns. One important step for Graham was to 7) step away from companies with debt. The higher the leverage, the higher the profits during economic expansion, but the faster a company would deplete its assets during recession. A company without debt can’t go bankrupt, which allows an investor to retain his ownership and wait for better times. Investors must research the market and (8) invest in companies that offer a significant earnings yield. The lower the price relative to historical earnings, the higher the safety given to investors. But, as we already know, a high earnings yield may sometimes not translate into high returns, in particular if management waste the money by retaining it or investing in unprofitable operations. In such cases it becomes possible to invest and 9) become an activist, to force the company into an efficient direction. Ultimately, an investor should never forget that statistics may also help mitigate risks and protect principal, through the power of (10) diversification.

The NCAV Strategy

One of the main strategies espoused by Benjamin Graham is the Net Current Asset Value (NCAV) strategy. The NCAV measures current assets minus total liabilities (both current and long-term). Graham calculated this value on a per-share basis and picked stocks for which their market price was below 2/3 of their NCAV. The reasoning behind this is straightforward. When NCAV is positive, a company is able to pay all its liabilities with just its most liquid current assets. If this value per share is below the share price, an investor is paying substantially less than the company’s liquidation value. If things go wrong, the company could be liquidated and still provide a profit to the shareholder. In a rational market, the explanation for this is that investors are expecting management to employ company resources in a wasteful manner. But Graham argues that market forces would soon reverse the process through two main mechanisms: 1) shareholders would press management (or even replace them) to pay out retained earnings in the form of increased dividends; and 2) the company would very likely be a takeover target, as other companies would certainly be happy to pay at least the liquidation value.

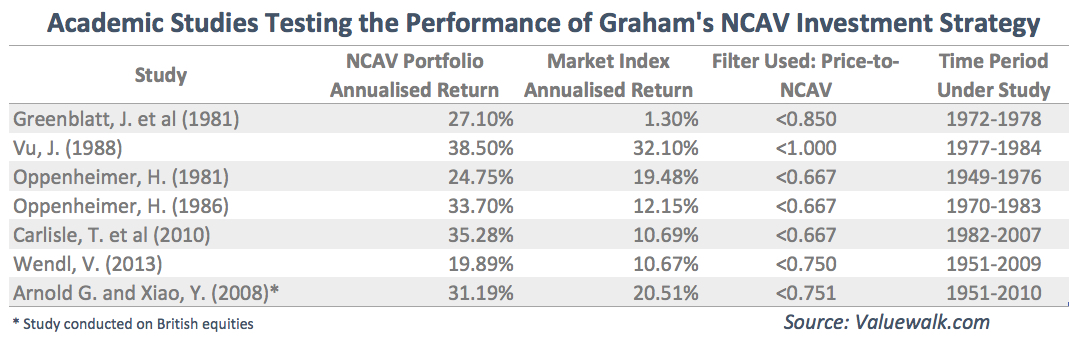

As there is no reliable track record of Graham’s strategies, a few academic studies have attempted to replicate the NCAV strategy to evaluate its performance. The central principle is to build a portfolio of shares with a price-to-NCAV value below a certain threshold and compare its performance with a market index. The following table summarises the results obtained in seven different studies:

In all cases the performance of the NCAV study has greatly exceeded the performance of the market index. In the case of the British market, performance for the NCAV portfolio has been 1.5x greater.

While the results seem great and are often lauded by online businesses providing share tips for a fee, I challenge the reader to find stocks priced at two-thirds of their NCAV value in today’s market. In fact, times have changed and it is extremely difficult to find stocks with that kind of undervaluation. Most of the above studies rely on data from decades ago. If undertaken today, they would lack significance.

Final Remarks

While some of the main strategies followed by Graham in his time are no longer readily available today, his main commandments should still form the basis for any long-term investment strategy executed today. Investors should focus on fundamentals and ignore others’ advise; they should think outside of the box and act against the herd; and they benefit from investing in assets carrying more cash, paying higher dividends, carrying less debt, and trading on low price ratios (price-to-book, price-to-earnings, price-to-cash), as a way of retaining a layer of protection against a potential drop in price. While doing this, investors should be patient, as “in the short run, the market is a voting machine” and sit it out for the long run, when the market “is a weighing machine.” But in doing that, they should never forget that “they are owners of a business and not merely owners of a quotation on the stock ticker”. It is up to them to change that business.

Comments (0)