Who will be the next Carillion?

For many dividend investors, the demise of Carillion was a disaster. Not only did their portfolios lose an important source of income, they also saw a permanent loss of capital. It’s easy to see what went wrong with hindsight, and in the August 2017 issue of Master Investor I wrote about some of the key lessons from Carillion’s collapse. Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but the problems with Carillion were not exactly hard to spot, even several years before its eventual demise. So rather than do yet another Carillion post-mortem, I thought it would be more useful to apply a little foresight and look for companies with similar “red flags” which investors might want to avoid or get out of.

There were four key lessons from Carillion, so I’ll be looking for four red flags: 1) Large contracts; 2) Weak profitability; 3) Big acquisitions; 4) High debts.

Interserve PLC

- Share price: 123p

- Index: FTSE 250

- Market cap: £170 million

Interserve is perhaps the most obvious “next Carillion”, having been in the media spotlight shortly after Carillion’s liquidation.

Like Carillion, Interserve operates in the cyclical Support Services sector. It mostly provides facilities management and construction services to both public and private clients, so the similarities with Carillion are clear. The company has also had its problems, resulting in a recently suspended dividend and a share price which has gone from over 700p a few years ago to around 100p today.

With results like that, many dividend investors will have already sold out. However, I still think it’s worth looking at Interserve because it’s a good example of how these four risk factors can bring previously successful companies to their knees.

Large contracts? YES

As a provider of cleaning, security, construction and other services, Interserve needs to win large long-term contracts to generate profits.

One problem with this business model is that these contracts are typically for a fixed period of several years, and when the contract ends, the associated revenues and profits disappear as well. This can make large contract-based businesses riskier than other businesses with smaller and more frequent sales “wins” (such as companies selling soap or toothpaste).

Another problem is that these contracts can be very costly if they go wrong. A good example of this is Interserve’s Glasgow “energy from waste” contract. In May 2016 the company announced that problems with the design, procurement and installation of a gasification plant, plus challenges with the supply chain, would lead to overruns and delays with an expected cost of £70 million. In February 2017 that expected cost was increased to £160 million and today it stands closer to £200 million. To put that in context, Interserve’s average net profit over the past decade has been £40 million to £50 million per year.

Weak profitability? YES

Yet another problem with large contracts is that they tend to attract “suicide bidders” – i.e. companies who will bid for a contract at a price which is almost certain to produce a loss, just so that their staff have something to do. This may seem daft, but it’s usually better than having skilled staff sitting around doing nothing. It’s also better than laying them off only to have to re-hire them at a later date (assuming they haven’t found a better job with a competitor).

Industry-wide suicide bidding leaves many support services companies with barely acceptable levels of profitability. Interserve fits that description, with post-tax return on capital employed averaging just 7.7% over the last decade. With the FTSE All-Share returning about 7% per year over the long-term, Interserve’s rate of return is not exactly impressive, although it did just about meet my profitability rule:

PROFITABILITY RULE: Only invest in a company if its ten-year average return on capital employed is above 7%

In terms of Interserve being the next Carillion, weak profitability is a sign of weak or non-existent competitive advantages. Companies with weak competitive advantages are vulnerable to industry downturns because they have little or no pricing power. They must undercut the suicide bidders and hope that somehow they can still eke out a profit. That is not a good position to be in.

Big acquisitions? YES

When a company wants to grow but cannot grow its core business, one easy way to boost short-term growth is to acquire other companies, and that’s exactly what Interserve set out to do in 2010.

In that year’s annual results, the company announced its intention to double earnings per share, from 40p to 80p, by 2015. The results also stated that the company’s then-reasonable borrowings of £121 million gave it “the financial strength to supplement organic growth with acquisitions”. So with the goal of doubling earnings in mind, management went on a massive debt-fuelled acquisition spree.

Between 2010 and 2014, the company spent about £430 million in cash acquiring other businesses, including £250 million (in cash and shares) for Initial Facilities, the facilities management business of Rentokil Initial PLC. Over the same period the company generated post-tax profits of about £210 million, or less than half the amount it spent on acquisitions. That was a serious red flag according to my acquisition rule:

ACQUISITION RULE: Only invest in a company if it spent less on acquisitions over the last ten years than it made in adjusted post-tax profits

Why might this make Interserve the next Carillion? Because a) companies being acquired don’t exactly shout about their problems from the rooftop; b) acquisitions add complexity and can distract the acquirer from their own (often weak) core business; and c) acquirers often overpay because of overoptimistic beliefs about synergies, cost savings and other potential benefits.

High debts? YES

With £430 million spent on acquisitions between 2010 and 2014 and total profits in that time of £210 million, it was always going to be hard for Interserve to pay for that lot using spare cash thrown off from its existing business. The answer, of course, was to borrow the money instead.

The bulk of those borrowings came in 2013 and 2014, when the company’s total borrowings went from £50 million to £370 million. That debt expansion took the company’s borrowings from just over one-times its then-average profits of about £40 million to almost ten-times. That was another red flag according to my debt rule:

DEBT RULE: Only invest in a cyclical company if its total borrowings are less than four-times its five-year average adjusted post-tax profits

By that standard, Interserve had gone from prudent to reckless in just a couple of years. In fact, things have become considerably worse since 2014, with the company’s debts ballooning to more than £460 million (and potentially much more in the soon to be released 2017 results), which is more than ten-times its latest average profits. Exactly why institutional investors signed off on all this is beyond me (I guess they get paid either way).

And it gets worse. On top of that £460 million (or more) debt-pile, Interserve has a pension obligation of more than £1,000 million. That is a literally unbelievable financial obligation for a company that makes barely £50 million or so each year. It’s also yet another red flag according to my pension rule:

PENSION RULE: Only invest in a company if its total pension obligation is less than ten-times its five-year average adjusted post-tax profit

Of course, the pension fund has assets, but the fund still has a deficit of more than £50 million, and given the £1,000 million size of the fund it’s possible the deficit could get a lot worse. This deficit is nowhere near as bad as Carillion’s astonishing near-£600 million pension deficit, but it does take Interserve’s combined debt plus pension deficit “borrowings” to more than £500 million, which is way too high in my opinion for a £50 million per year company.

Is Interserve the next Carillion?

Obviously, I have no idea whether Interserve will go into liquidation like Carillion. Its situation is bad, but not as bad as the jaw-droppingly bad state of affairs at that other company. However, I think the situation is bad and a rights issue of several hundred million pounds could be the best option, assuming shareholders are willing, which they may not be.

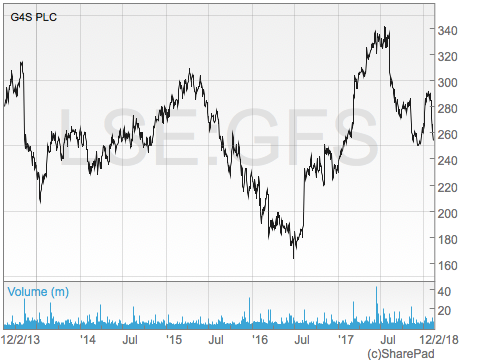

G4S PLC

- Share price: 291p

- Index: FTSE 250

- Market cap: £170 million

G4S is another company operating in the Support Services sector. It’s the world’s leading security services company, born from the merger of Securicor and Group 4 in 2004. It’s a company that only seems to make the headlines when things go wrong, such as Group 4’s problems with escaping prisoners in the 1990s or G4S’s failure to provide enough security personnel during the 2012 Olympics.

Large contracts? YES

G4S earns its profits by providing security services (such as security personnel or security systems and technology) to clients through sometimes large and long-term contracts. I’ve already outlined the potential problems with this business model, so rather than go over them again let’s have a look at what happens when things go wrong.

Remember the London Olympics in 2012? As official security services provider for the games, G4S was in a good position to use this high-profile contract to increase its profits and its reputation around the world. Sadly, it didn’t quite work out that way. Rather than increasing its profits or reputation, G4S lost money and reputation at the 2012 Olympics. It failed to provide enough security personnel and, at the last minute, thousands of troops had to be brought in to make up the numbers. As a result, the CEO and other senior management lost their jobs and the company lost around £90 million on the contract.

This is precisely why large contract-based businesses are risky and why they should be treated with care. G4S makes around £200 million per year in post-tax profits and it lost around £90 million from a single contract. And of course, the long-term damage to its reputation may be far more serious than the short-term damage to its bottom line.

Weak profitability? YES

The average post-tax return on capital employed across all 220 companies on my stock screen is 11% and, as I’ve already mentioned, the long-term expected return of the FTSE All-Share is about 7% per year.

How does G4S compare to those benchmarks? Not too well. Over the last decade its return on capital employed has averaged just 5%, which is very unimpressive. It’s return on shareholder equity is better, with an average of about 18%. However, that higher return on equity is only possible because returns have been boosted with large amounts of borrowed money (which I’ll cover in a moment), and that increases risk as well as returns.

Big acquisitions? NO

In recent years, and especially following the 2012 Olympic disaster, G4S has shied away from large acquisitions. The last really big acquisition was in 2008, when it purchased Global Solutions Limited for £355 million. That acquisition cost more than an entire year’s profit (of about £200 million at the time) so it was big, but 2008 is ancient history now so this acquisition doesn’t bother me.

High debts? YES

G4S’s return on capital employed is very weak, so it uses large amounts of debt to boost shareholder returns. This is a legitimate strategy, but also a risky one if the debt burden becomes too large.

As I’ve already mentioned, I prefer cyclical sector companies to keep their total borrowings below four-times their recent average profits. For G4S, which has average post-tax profits of about £185 million (there has been little or no profit growth over the last decade) that would mean a debt-ceiling of about £740 million. In fact, the company announced total borrowings of more than £2,500 million in its latest annual report.

But is this enough to make G4S the next Carillion? It’s possible, especially given that G4S has almost three times as much debt as Carillion on a debt-to-profit basis. And the fact that its debt interest payments are equal to about 50% of its post-tax profits is not exactly a good sign either.

For more insight and analysis like this, CLICK HERE to read Master Investor Magazine for FREE.

This massive debt burden is more than enough to make G4S a very risky proposition in my opinion, but it gets worse. The company also has a massive pension obligation totalling some £2,700 million. That gives the company a pension obligation to profit ratio of 15, well above my preferred maximum of ten.

This huge pension also comes with a huge deficit of £341 million, taking G4S’s combined debt plus pension deficit liabilities to almost £3,000 million, which is a vast amount for a company generating less than £200 million in profits. And don’t think this is just an accounting anomaly with no impact on cash flows, because it isn’t. G4S is currently obliged to pay around £40 million per year into the scheme to close the funding gap, with that amount increasing by 3% per year.

Is G4S the next Carillion?

G4S’s debt and pension obligations relative to its profits are in the same ballpark as Carillion’s were just before it collapsed, so the company certainly seems to have the right characteristics to be the next Carillion. However, G4S has put out positive trading statements recently and has so far maintained its dividend, unlike Interserve which has already suspended its dividend.

A maintained dividend might reassure investors, but it’s exactly what I would expect to see. Long experience has taught me that CEOs will almost always paint a positive picture and, more importantly, maintain the dividend. They’ll do this even when it seems obvious that the sensible thing to do is to suspend the dividend and use the cash to reduce debt and pension obligations (and perhaps even raise a little extra cash through a rights issue).

But what is sensible and what keeps a CEO in their job is not always the same thing, as Carillion’s shareholders know all too well.

Of course, I’m not saying that G4S or Interserve are going to go bust or that their management are incompetent, but both companies have a lot of characteristics which make them look very similar to Carillion. That’s why I won’t be buying either company, no matter how low their share prices go. And just as importantly, I’ll be looking to avoid any other companies with a similarly risky combination of large contracts, weak profitability, big acquisitions and high debt and pension obligations.

Good article; the large debt levels of these companies highlights the dangers in linking executive compensation too highly to EPS growth (driven by return on equity), which can be temporarily inflated through large borrowings but leave the company vulnerable to collapse when things go south.

Management intent on inflating short-term earnings at the expense of the company’s long-term financial health, coupled with a board of directors who fail to hold them to account, is a very dangerous combination.