A New Investment Paradigm? NIRPs & Equity Valuations

Are we entering a “new normal” in asset valuations? In an interesting recent piece in the Telegraph, Tom Stevenson, investment director at Fidelity Worldwide, suggested that the current trend for central bank negative interest rate policies (NIRP) that we are seeing across the globe – and their subsequent impact on rising equity values – could actually represent a “new investment paradigm”. He rightly added that such discourse could potentially be pernicious; after all, it is for good reason that the words “this time it’s different”, can be some of the most expensive in the English language. As in: “Boom and bust”, maybe? Pah! Nonetheless, as a practitioner and avid student of financial valuation, the concept certainly raises some interesting points and potentially challenges textbook corporate finance theory. So how did we get here?

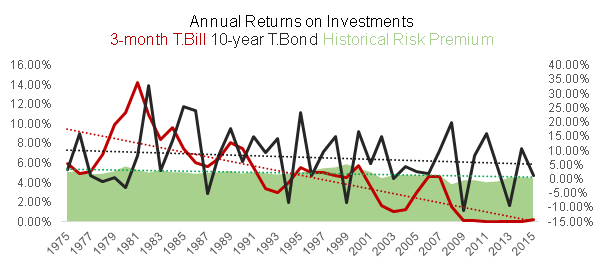

Over the last 40 years, yields have been on a downward trajectory. The Financial Crisis of 2007-09 accentuated this trend. In response to the crisis, central banks lowered interest rates to historically low levels. In 2009 and 2010, this was seen as merely a temporary solution: with the coming uptick rates would spring back to normal. However, the goalposts of monetary “normality” kept shifting. In 2011 and 2012, the conviction was that as central banks rolled back QE programmes, interest rates would naturally rise. In 2013 and 2014, various crises (such as the ongoing Greek tragedy) were blamed for continued depressed rates. By 2015, commodity price deflation and an anticipated Chinese slowdown were the key culprits. Rate rises were always just around the corner. Last year, short-term interest rates in the Danish Krone, Swiss Franc and the Euro dropped below zero. Sweden and Japan were the next dominoes to fall into negative territory. The US could be next.

Just to be clear, NIRPs mean that a bond holder is in effect paying a government to borrow money and that banks are charged for deposits held at some central banks (so far commercial banks have been reluctant to pass this on to customers) as central banks hope to increase the velocity of money for savers, investors and businesses.

Long-held assumptions of financial theory are being challenged. The time value of money – the fundamental basis for global asset valuation and investment – states that capital has an implicit opportunity cost involved. That is, a rational agent prefers to consume now rather in the future, due to inflation, default risk and expenditure preference. (Would you rather have an Aston Martin today or tomorrow?) To delay this consumption, the agent would need to be compensated, usually in the form of financial return (interest or capital gains). The greater the inflation or default risk, the greater the return demanded. This is essentially the building block of valuation: a bird in the hand is worth more than two in the bush.

That is why it is challenging to reconcile the fact that currently, there are $10 trillion in total negative-yielding sovereign bonds outstanding globally. Furthermore, over 25% of the total value of J.P. Morgan’s global government bond index has a below-zero interest rate. Corporate debt is also starting to be impacted.

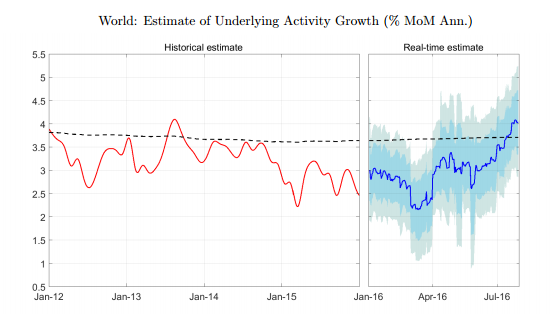

Now, such a dynamic would make sense if deflation is expected. But this doesn’t seem to be the case. Inflation-linked securities are flagging upside momentum. Moreover, Fulcrum Asset Management’s August “Nowcast” identified a broad pick-up in growth in both developed and emerging markets.

Henderson Global Investors’ proprietary six-month real M1 money measure also supports this view. Of course these data points could be ephemeral noise. However, with 48% of the positive-yielding sovereign debt not held by central banks being U.S. Treasuries, competition to buy U.S. debt could drive Treasury rates even lower.

Moreover, we are not just talking about a short-term dynamic. Swiss government bond yields all the way out to 50-year maturities have now all turned negative. The trend towards ZIRP (zero interest rate policies) and then NIRP represents a potential investment game changer, or as Tom argued, “equity investors are following their counterparts in the bond world in starting to think that maybe it really is different this time… as the ‘lower for longer’ interest rate outlook mutates into ‘lower forever’”.

An interesting lens to explore the impact of negative rates on equities is through the discounted cash flow model (DCF). Finance 101 tells us that the value of any asset can be expressed as the present value of it’s expected future cash flows. We calculate the present value through an appropriately fitted discount rate. One of the main approaches to calculate this opportunity cost is via the CAPM, which is a function of a risk-free rate, the systematic risk of a security and an equity risk premium. A sustainably lower risk-free rate would then, ceteris paribus, mechanically reduce average costs of capital (both equity and debt), adjusting stock valuations upwards.

Denmark and it’s stock market (^OMXC20) could provide a practical example. Since 2012 it’s been a place where you can get paid to borrow money and charged to save it. The index has more than doubled over this timeframe.

A new investment paradigm would then entail such an upside being applied to global markets as NIRPs increasingly become the “new normal” as costs of capital are reduced and – as the argument goes – valuations are automatically pushed upwards.

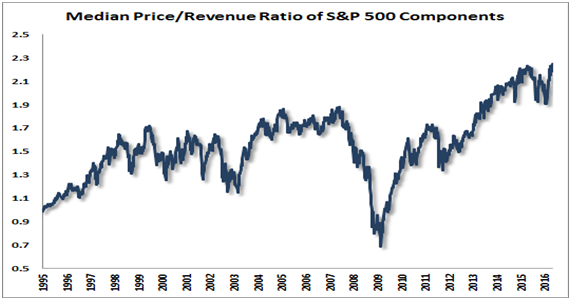

Recent insight from the Federal Reserve flags up a few interesting points. Forward price-to-earnings ratios for equities have increased to a level well above their median of the past three decades. That is above even 2000 and 2007 levels. Is this time different then? The Fed do add that stocks are indeed vulnerable to a term premium return to normal. However, the macro idea behind the “new investment paradigm” of NIRPs is that what is normal has shifted. Bank stocks are particularly vulnerable in this brave new world.

In previous crises we have seen short-term interest rates below zero, but this is the first time that long-term interest rates have turned negative. Of course, we need to be clear that in general we are talking about negative rates for base rates at central bank who, via discount rates and their open market operations, can only signal to the market the path they believe inflation and real growth will take in the future and hope the market listens to such “forward guidance”. The objective, in a nutshell, similar to QE, is to leverage negative rates to increase asset prices for financial assets and enhance investment via the aforementioned artificially lower hurdle rates (leaving aside potential beggar thy neighbour currency devaluation effects). It´s a compelling argument and as discussed, central to the new investment paradigm rationale. But is it that simple? Does it – indeed will it – work?

The author recently took part in an event in São Paulo with Professor Damodaran – the leading global authority on valuation – where he admitted that negative rates made him uncomfortable but that as valuation and corporate finance professionals we had not only to make sense of them but also to live with them.

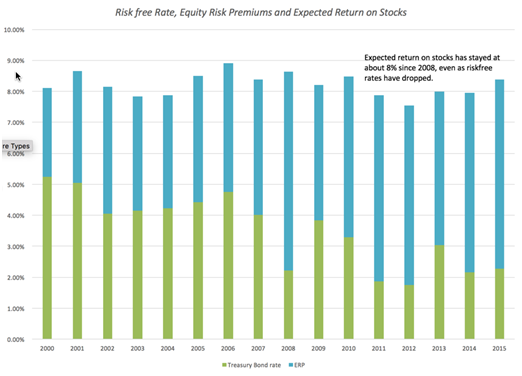

He argued that as interest rates in the occidental economies have hit new lows, real investment has not materially increased and that whilst stock prices have broadly seen upward pressure (S&P500 +94% over 5 years, 05/08/16), rising earnings and cash flows have also been key factors. Damoradan´s view was that central banks have potentially miscalculated in assuming that interest rates always follow the central bank lead (a case of the emperor’s clothes?) and that risk premiums on equity and debt could actually increase as rates go down, lowering financial asset prices and reducing real investment.

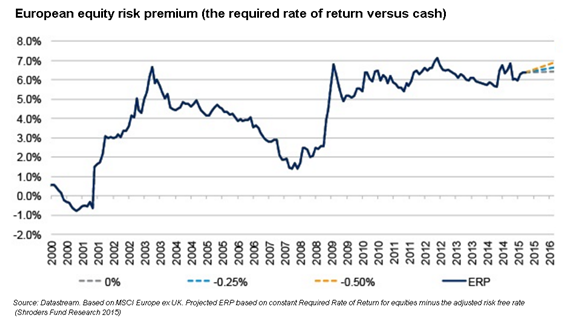

His data suggests that as the risk-free rate has dropped over the last few years the expected implied return for stocks has stayed around 8% during that period, leading to higher equity risk premiums. The impact on cost of equity discount rates could actually be net zero (see the graph below). There is no free lunch. As always then, over the long term, valuation is driven by the fundamental narrative.

We are seeing an unprecedented situation where nominal interest rates in a number of European countries are negative across a range of maturities. To the BIS the upshot is that, instead of paying interest, a number of governments in continental Europe are now being paid to borrow. For their part, investors are currently not compensated for taking interest rate risk. It is worth adding that such “investors” are also to a large extent the very central banks that are behind the NIRPs in the first place. The largest four central banks bought assets worth $1.2 trillion in 2015, similar to the amounts purchased post-Lehman and during the 2013 euro-area crisis, with only $400 billion of additional government debt sold to the private sector (BoE data).

What is clear though is that we are in uncharted territory, a new investment paradigm indeed, but not necessarily a positive one. There may certainly be some potential negative externalities and unintended consequences, but – to paraphrase Zhou Enlai on the French Revolution – it could be too early to tell what path they will take. What is interesting in a NIRP world is is the erosion of the concept of “risk-free” assets. Do not such “safe” assets become riskier by definition?

PIMCO argue that negative interest rates may act to increase risk aversion and uncertainties across the financial system. As yields are pushed into negative territory, holding these bonds represents a guaranteed loss of purchasing power if held to maturity. In essence, perceived risk-free and other high quality assets are being removed from the financial system and replaced with riskier, negative-expected-return assets. While that may encourage some investors to take more risk to compensate for loss of income, others will certainly be forced to reduce risk in response.

Perhaps then, not all NIRPs are created equal. We can juxtapose the Danish example with the curious case of Japan where the move into negative territory at the start of the year was broadly seen as a “risk off” signal. The Nikkei (NI225) has fallen 11% YTD (05/08/16) whilst the Yen unexpectedly strengthened as investors fled into traditional safe-havens. In both cases the stories behind NIRP were different. In Denmark the objective was to limit Krone appreciation whilst in Japan the aim was to stimulate growth. This takes us back to the fundamental valuation narrative.

Thus, if the underlying reasons for low and negative rates are lower growth and inflation expectations (which basically they are) then they are bound to impact future cash flows. Since the GFC, there has been an assumption that “all bad economic news is good news” because it brought renewed monetary stimulus. Well, we are perhaps arriving at the limits of central banks’ conventional unconventional tool kits. This could partly explain the rise in risk premiums and impaired business investment. As BoE Governor Mark Carney himself put it: “the effect of QE on the wealth channel cannot last forever. Monetary neutrality means real asset prices are not boosted indefinitely by such policies. Said differently, unless an improvement in fundamentals boosts the underlying cash flows of these assets, real valuations will fall back”.

Temporal issues here are key. Over the short term, the global hunt for yield in an ongoing NIRP milieu, asset prices being pushed upwards by potential new rounds of global QE (the BoE kicking things off with a monetary policy response to Brexit) and reduced costs of capital could all combine to positively impact equities. Moreover, if ZIRPs & NIRPs are here to stay over the medium term, would equities not rise as bonds remain less attractive? Reduced hurdle rates across the board could also mechanically push up broader asset valuations in the real economy. Nonetheless, lower debt costs do not necessarily mean lower WACCs (working average cost of capital). Likewise, if the macro picture does not improve, the other side of any new investment paradigm would be weaker fundamentals and thus weaker valuations as cash flows are marked down accordingly.

Or this time it’s different?

About the Author

Adam Patterson is an economist from the UK, currently living in Brazil where he is founder of a valuation fintech and partner in a corporate finance office. He has previously worked in the UK Parliament, various investment practices and HSBC Brazil. Adam’s research focus is on political economy, infrastructure investment, Brazilian financial markets and asset valuation. He read politics at Leeds and economics at the University of London as well as studying at the CISI. Adam also holds an MBA Finance from the Federal University of Paraná, Brazil.

Comments (0)