Mitie disappointment or Mitie dividend potential?

| First seen in Master Investor Magazine

Never miss an issue of Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

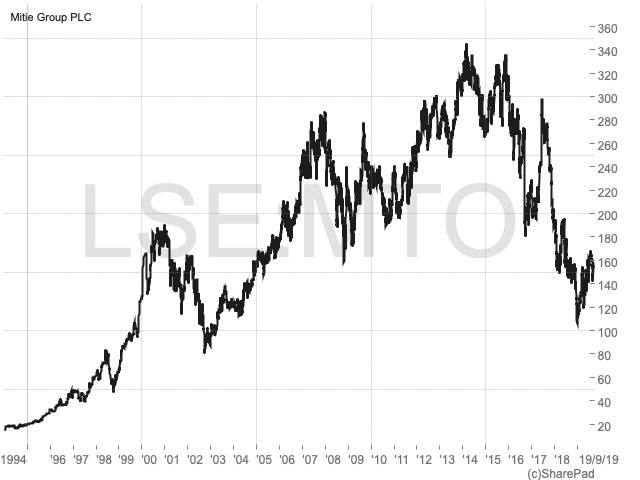

Mitie’s share-price performance has been disappointing of late. But with sensible management, the company could return to health in the coming years, argues John Kingham.

Mitie is the UK’s largest facilities-management (FM) company. In layman’s terms, that means it provides corporate and government clients with property-related services so they can focus more intently on their own core activities.

These services range from single-service offerings, such as security guards or cleaning, all the way to integrated FM (IFM). IFM means largely taking over all building-related operations. It goes beyond simple security, cleaning and engineering maintenance, and can include projects to improve the energy efficiency of a building; micromanaging an office’s temperature and humidity to optimise employee productivity (so that workers are, for example, less likely to fall asleep after lunch); or helping a company reduce its water, waste or carbon footprint.

After many years of outstandingly consistent and rapid growth, Mitie is now a turnaround story. In the last 10 years the company’s previous management made some serious mistakes, leaving Mitie unfocused, inefficient and over-indebted. In 2016 the dividend reached a high point of just over 12p before being cut to 4p in 2017, and that’s where it remains today.

With its share price currently close to 160p, Mitie has a dividend yield of just 2.5%. For an income investor that isn’t very interesting, and it shows that ‘Mr Market’ expects the dividend to head back upwards – sooner rather than later.

So, the investment case for Mitie hangs on whether that dividend can return to anything like the 12p it reached in 2016, or whether Mitie and its dividend have been damaged beyond repair. As usual, I’ll try to answer that by starting with a little history.

Management incentive through investment equity

Mitie was founded in 1987 and from the very beginning it was built around the idea that people could produce extraordinary results if the potential rewards were extraordinarily large. This idea was turned into reality through the Mitie Model, which gave entrepreneurs the opportunity to start, grow and eventually sell their own business, all with the help of Mitie.

Here’s how it worked: let’s say Bob, an employed heating engineer, wants to start his own boiler- maintenance business in Kent. Unfortunately for Bob, he doesn’t have sufficient start-up funding or a long-enough list of clients to make the business viable. Then he hears about Mitie, which is offering to help FM start-ups. Mitie will put up 51% of Bob’s start-up funds in exchange for 51% ownership of the new company. Mitie will also help with business management, accounting and other back-office needs, and will give Bob access to its existing clients. Finally, Mitie offers to buy Bob out of the new business in five years if Bob can grow its annual profits to £100k. Mitie will pay 10-times earnings, so Bob will make a cool million pounds in five years if he can keep up his end of the bargain.

How hard is Bob going to work under those conditions? Unbelievably hard. How effective is this as a way of scaling up a conglomerate of start-ups? Amazingly effective.

This, along with a string of bolt-on acquisitions, is how Mitie managed to grow revenues by a compound rate of 40% per year for more than 20 years.

Driving rapid growth by dangling enormous carrots in front of people is an obvious and effective way to grow a company. But the approach has several limitations, of which I’ll mention two.

Startups, scale and the lure of big acquisitions

The first problem is that the number of available plumber, painter or security-guard start-ups did not keep pace with Mitie’s growth. For example, let’s say Mitie can find 10 good entrepreneurs to back each year. At the end of year one Mitie consists of 10 start-ups. At the end of year two it has 20, double the number it had a year before. By the end of year five Mitie owns 50 start-ups, but adding 10 start-ups in year six will only increase their number by 20%. And every year bolting on 10 more start-ups will produce less and less growth in percentage terms.

After 20 years, the impact of a few more Mitie startups becomes inconsequential to a conglomerate with more than a billion pounds of revenue and almost £50 million pounds of profit. So, to keep the Mitie growth juggernaut thundering along, management turned to the obvious solution: large debt-fuelledacquisitions. Unfortunately, this is rarely a good idea.

| First seen in Master Investor Magazine

Never miss an issue of Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

In Mitie’s case, its debts went from virtually zero in 2005 to £200m in 2011. Much of this debt was used to fund almost £300 million of acquisitions, with the gap funded via rights issues (ie selling new shares to shareholders).

Mitie’s acquisitions during this period started out quite sensibly. For example, it spent £90m on security- guard companies in 2006, making Mitie the second-largest provider of security guards in the UK. It also spent £130m on an engineering-maintenance company with a focus on energy-efficiency technologies for offices and other buildings.

Later acquisitions, such as the £40 million spent acquiring a social-housing-maintenance business, were less obviously related to Mitie’s core business, which was to provide FM services to offices, shops, factories and government buildings.

By 2011 Mitie had borrowings of £200 million and 10-year average net profits of £38 million. That gave the company a debt to average profits ratio of 5.3, which is above my preferred maximum of 5.0. However, it wasn’t nearly enough for Mitie’s management, so in 2013 they took another risk and spent almost £120 million acquiring a business providing care at home to the elderly.

I have no idea what providing care to elderly people has to do with Mitie’s core business of cleaning, guarding and maintaining large office buildings, shops and factories, but Mitie’s management seemed to think it was a perfect fit.

This final big acquisition took Mitie’s total borrowings to a very worrying £290 million, giving the company a debt to average profit ratio in 2013 of 7.0. That’s way beyond anything I’d call prudent. However, even with that enormous debt pile I think Mitie may have been able to avoid the crisis of the last few years if its internal structure had been highly standardised, optimised, efficient and effective. But it wasn’t.

A big ball of mud

I said earlier that there are (at least) two problems with an acquisition-driven growth strategy (in Mitie’s case it effectively grew by acquiring start-ups). The first is that you eventually get too big to grow by bolting on start-ups and that often leads to the dark path of debt-fuelled acquisitions. The second problem is structural. In other words, if you grow a company by lumping together dozens or even hundreds of start-ups and other acquisitions, it’s very easy to end up with a ‘big ball of mud’.

A big ball of mud is a phrase from the world of computer programming, where badly structured systems are all too common. Here’s the original definition from Brian Foote and Joseph Yoder:

“A Big Ball of Mud is a haphazardly structured, sprawling, sloppy, duct-tape-and-baling-wire, spaghetti-code jungle. These systems show unmistakable signs of unregulated growth, and repeated, expedient repair. Information is shared promiscuously among distant elements of the system, often to the point where nearly all the important information becomes global or duplicated.”

This lack of organised structure started to show up in 2013 when the company began offloading its struggling contract-engineering businesses, which did engineering work on a one-off basis, rather than as part of a long-term FM contract. At one time these businesses had been a significant part of the company, but Mitie’s sprawling array of services made it incapable of competing in such a highly competitive, low-margin market against more focused competition. Exiting these businesses eventually cost Mitie more than £120 million.

Mitie’s haphazard, sprawling structure also made it hard to pin down exactly what its core business was. Was it security guards? Cleaners? Designing energy-efficient lighting systems or waste-to-heat power plants? Or was it project-management consulting? The lack of focus meant that the previous management team felt comfortable acquiring a homecare business and social-housing-maintenance businesses. Unfortunately for shareholders, these large and expensive acquisitions eventually proved to be too unrelated to Mitie’s core FM business, and both were eventually sold at a loss.

While the big ball of mud structure almost inevitably leads to a crisis, it isn’t necessarily a death sentence.For example, Compass Group (LON:CPG), the world’s largest catering company for corporate clients and a previous holding in my portfolio, grew by acquisition until it was bloated, unfocused and loaded with debt. The turnaround began in the mid-2000s. Compass sold off non-core businesses and used the proceeds to pay down debt while building a highly efficient, narrowly focused core catering business. After a multi-year turnaround effort, Compass has gone on to be very successful over the last decade, and I think Mitie could do the same.

Narrow focus, effective structure, strong foundations

With the old management team long gone, Mitie is now somewhere close to the middle of a multi-year turnaround effort.If Mitie is to replicate Compass Group’s successful transformation from a big ball of mud into a lean, focused growth machine, I think it needs three things:

1) More focus: instead of working with both government (local and central) and business (small, medium and large), across single or multiple sites, offering single, bundled or fully integrated FM services, Mitie needs to become much more focused in terms of the clients it goes after and the services it offers them.

| First seen in Master Investor Magazine

Never miss an issue of Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

Fortunately, this is exactly what the company is now trying to do. Gone are the short-term contracting businesses, along with care for the elderly and social housing, replaced with a greater focus on providing fully integrated FM services to large blue-chip clients. Although Mitie will still provide some clients with single services such as security or cleaning, this is a shrinking part of its business and in my opinion that’s a good thing. Unlike the complex business of optimising every aspect of a company’s buildings across multiple sites, single services such as cleaning or security are more of a commodity, with lots of competitors and low profit margins.

2) Better structure: growing by bolting together dozens of painting firms, cleaners, decorators, roofers, security companies, engineering contractors and consultants was always going to be problematic at some point. Now that Mitie has long since reached that point, a better internal structure should give the company a lower cost base through greater efficiency and better services, thanks to more consistent processes and the ability to quickly learn from its numerous successes and mistakes.

To be fair, Mitie has been working to integrate its companies since the 1980s, although it clearly didn’t do a good job (otherwise it probably would have avoided the current crisis). But at least it’s doing the hard work now. It has spent much of the last three years working through Project Helix, a £50 million effort to adapt Mitie’s DNA from that of a loose collection of companies to one more fitting of a single, fully integrated business, which is exactly what large blue-chip clients want to interact with.

3) Less debt: even the sturdiest building will crumble if its foundations are not strong enough to withstand the mildest of earthquakes. In the same way, a strong company will crumble at the next recession if its balance sheet is weak. And with total borrowings of almost £270 million (almost eight-times its 10-year average profits of £35 million), Mitie’s balance sheet is definitely still weak. In fact, if you factor in Mitie’s £75 million or so defined-benefit pension deficit then its debt mountain begins to look almost insurmountable.

For me, this is the most disappointing aspect of Mitie’s restructuring effort. Despite offloading numerous underperforming non-core businesses, the (meagre) proceeds from these sales have barely reduced the company’s debts at all. However, that may be about to change as Mitie recently announced the sale of its catering business for £85 million. That should help the company reduce its debts by a significant amount and focus more acutely on the areas where it does have the necessary economies of scale to compete (such as security, cleaning, engineering maintenance and the fully integrated and endlessly optimising ‘smart workplace’ of the future).

Future prospects and valuation

I think it’s likely (ie twice as likely to occur as not) that Mitie will make it through this restructuring phase successfully.Like Compass Group, I think it has strong core businesses in security, cleaning, engineering maintenance and integrated FM, and it has the market-leading positions and scale in these areas to compete with the best FM companies in the UK.

It has been working through this restructuring phase since 2013, with many non-core businesses already exited and many millions of pounds and years of effort put into upgrading the company’s operating system to something much more efficient and effective. This process continues with the recent sale of its catering business and the launch of Project Forte, a renewed effort to drive simplicity and efficiency in Mitie’s largest business (engineering maintenance).

In terms of the numbers, if you strip out the losses from exiting businesses and the cost of internal restructuring, then Mitie returned an average of 15% on capital employed over the last decade, which is comfortably above average. Its revenues have also been very steady over the years, showing that FM should be a relatively defensive activity. Another plus is that Mitie isn’t very capital intensive, which means if management can meaningfully reduce its debt pile it shouldn’t need to load up on debt to invest in growth assets (such as new buildings, factories, supertankers etc.).

On the downside, average profit margins are thin at 3.3% (again, adjusted to take out non-recurring costs), which may make profits more volatile, but that’s the nature of the FM industry; you either accept it or you don’t (and as a general rule I don’t). And then we have the company’s still weak balance sheet. However, hopefully that will become less of a problem if the proceeds from its catering business are primarily used to pay down debt. Also, if Mitie does show a sustained recovery over the next five years, I think it would be best if management kept the dividend at its current depressed level of 4p and used the excess cash to lower Mitie’s debts to no more than £100 million.

So, by 2025, I think it’s likely that Mitie will have a repaired balance sheet and a healthy core business generating earnings per share of around 15p, which is still less than it managed a decade ago. With earnings of 15p it would be able to easily afford a 10p dividend, which would be a yield of 6.3% on today’s share price of 160p. And if the dividend can return to steady growth after that, of perhaps 2% to 5% per year, then I think it’s likely that the share price would double from where it is today, perhaps reaching 300p or more and giving the company a reasonable yield of slightly more than 3%.

Obviously, that’s conjecture, and as a Mitie shareholder since 2011 I am more than used to being disappointed. But I still think Mitie is fundamentally a good company, and that with sensible management it’s likely to do well over the next five to 10 years.

Comments (0)