Meet the European bank bucking the trend

Banco Santader buys Banco Popular

It’s always intriguing to read in the news that one big European bank just purchased another, in particular at a time the clouds hanging over European banks are dark and wide. But perhaps those clouds are not as large as many perceive, or maybe they don’t cover the whole European sky. The prolonged financial crisis that hit sovereigns and banks also created big opportunities for some entities. One of those seems to be Banco Santander (BME:SAN), which has been shopping at wholesale prices, while taking the opportunity to gain market share in key markets. At a time when few European banks seem to have the firepower for acquisitions, Santander purchased Portuguese bank Banif (at the end of 2015) and Spanish lender Banco Popular (6th June 2017).

The news of the acquisition outlines three important points relating to European banking: (1) Banco Santander has been building a strong financial position, which will likely translate into an increased market share at a time when the economy is turning more positive; (2) the new EU bank resolution framework is a success, as it has proven able to deal quickly with a bank failure before it translates into market instability and without creating a burden on the taxpayer; (3) banks’ shareholders and junior bondholders do incur financial risks (as should have always been the case).

Always save for a rainy day

The greatest value investors of all times – Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett, John Templeton, Peter Lynch, among others – always worried about purchasing good companies with promising businesses, at reasonable (if not largely depressed) prices, to weather out any unfavourable short-term price movements. In a certain way that means that leverage may be a problem because it amplifies losses. From the perspective of an investor, too much leverage means having to sell sooner to comply with margin requirements. From the perspective of a company, too much leverage means being out of business in case economic conditions (not under the control of the company) turn unfavourable.

During the 1990s and 2000s, banks took the opportunity presented by central banks to raise money out of thin air, to completely overturn the savings system. Banks were creating deposits out of credit, instead of deposits being used to lend money. The fractional reserve system allowed banks to boost leverage through the roof while securitisation further increased that leverage. All this pushed banks into taking an active role in the economy, boosting the construction sector at first, and then everything else due to knock-on effects. They failed to realise that the correlation between banks’ loan portfolios was too high, such that any slowdown in the economy would significantly increase the number of non-performing loans and eat up banks’ provisions for bad loans. With leverage being too high, a small rise in the rate of non-performing loans would be enough to eat up a bank’s liquidity and lead it into bankruptcy. Everyone knows what happened next…

So, being able to evaluate the true risk during times when everyone is euphoric is difficult, but a key ingredient of long-term success. A company sometimes needs to pass on promising projects just to stay clear of problems further down the line. As a Spanish bank, Santander was highly exposed to the euphoric mortgage lending market that culminated in disaster in Spain. But the bank has always been more conservative than others, which helped it survive the crisis and strengthen its future position.

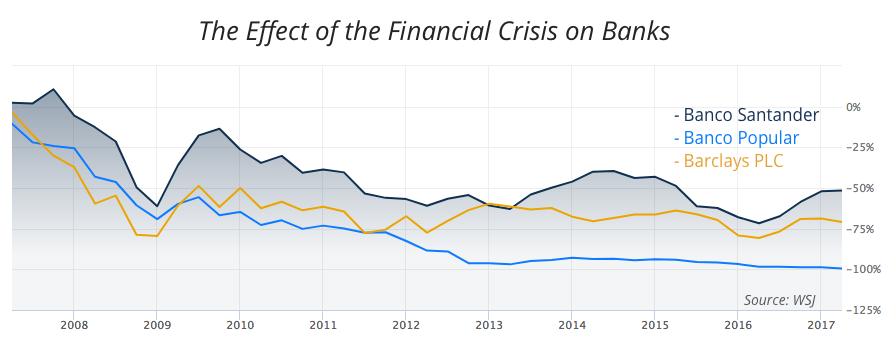

No one escaped the financial crisis that hit Europe. The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 and its aftermath battered down shares of Santander from above €13 at the beginning of 2007 to €4.65 at the beginning of 2009. With the broad market then recovering from the burst bubble, Santander’s shares recovered to €10 in October 2009, but were battered down again during the second round of the crisis that hit European sovereigns and banks. Shares experienced a descent that lasted until mid 2013, when they were priced at €4.45. After a small recovery, the shares continued the descent to €3.40. While the loss for Santander shareholders reached 74%, the loss in many other European banks was much worse. Santander’s shares now trade at €5.80, and are recovering at a very fast pace from their lows in 2016.

While Santander couldn’t avoid the negative impact of the crisis, its more prudent risk management allowed the bank to manage through the crisis without putting its continuity at stake. A conservative use of balance sheet resources allowed the bank to be in a position to buy competitors’ assets at a time when no other could. That was the case with the purchase of the reatil network of Banif in 2015, when Banif was nearing insolvency. Santander was able to purchase only the good assets from the bank, at depressed prices, due to the emergency nature of the situation and the Portuguese economic conditions at the time. At a time when other Portuguese banks like BES, CGD and Millennium were struggling to survive, Santander had no serious competition to its bid. The bank consolidated its position in the Portuguese market, becoming the second largest and the most profitable.

The case of Banco Popular is another example of how it may be worth keeping some cash to hand. The troubled bank had never recovered from the burst of the Spanish housing market bubble, as it still carries €37 billion in toxic real estate loans on its balance sheet, after losing €3.5 billion last year. Management has been working hard to find a buyer for the bank’s assets over the last few weeks but failed to find one. Banco Popular shares have lost 50% in just the four initial trading sessions of June. Raising new capital was practically impossible. Santander waited for the recently created EU Single Resolution Board (SRB) to step in and declare the bank as “failing or likely to fail” and then made a deal to purchase the bank for €1.

The new EU framework

The sale of Banco Popular marks a new way of dealing with bank failures in the EU, under which bail-in replaces the bail-out model that hit governments’ finances, and ultimately the taxpayer, in the recent past. The Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) establishes the framework to deal with bank failure in a way that minimises the cost to taxpayers, while still preventing financial instability. The Single Resolution Mechanism Regulation (SRMR) sets out specific provisions for member states participating in the banking union for the cases where banks encounter difficulties. In conjunction, the BRRD and SRMR set the new framework of action, which provides competent authorities the power to deal with bank failures in a way that preserves the continuity of the banks’ critical functions while avoiding the use of public (taxpayer) money.

The main idea behind this creation is to have an entity – the Single Resolution Board (SRB) – that is able to identify a potential bank failure soon enough to preserve the main operations at the cost of the banks’ shareholders and junior bondholders without having to inject any money in order to solve the problem. In general, three conditions should be met before the SRB determines a bank should undergo resolution: (1) the bank is failing or likely to fail; (2) there are no alternative private solutions or supervisory actions that would prevent the bank failure; and (3) a resolution action is necessary in the public interest. When these conditions are met, the SRB has the powers and tools to restructure a failing bank by selling all or part of its assets and liabilities to any third parties, and to allocate any losses to shareholders and creditors.

In the case of Banco Popular, it was clear that the bank couldn’t raise any money alone and the SRB decided to assign all losses to shareholders and junior bond holders and sell the remainder of the bank to Santander for €1, in a deal that was just approved by the European Commission.

Well prepared for the future

The acquisition of Banco Popular by Banco Santander will still require an injection of €7 billion from the acquirer, but the new bail-in model gives a good cushion by having wiped out previous creditors and shareholders. This model should have long since been adopted by the EU in order to allocate losses to all those who risk their money for an above risk-free return instead of allocating losses to depositors and taxpayers. In Italy, this model seems to have found some setbacks, but the result with Banco Popular is inspiring for the future because the SRB was able to solve the issue in a swift way without creating any discontinuity in banking operations. In the future, banks’ shareholders and unprotected bondholders should be aware of their real risks. A few banks in Italy and Portugal may already be in the queue.

As for Santander, I believe the bank is a good long-term investment. The deal will give it access to the small- and medium-sized business lending market in Spain, where Banco Popular used to excel with an 18% market share. It will additionally help consolidate Santander’s market share in both Spain and Portugal. The bank is currently positioned as the 20th largest bank in the world by assets and 19th by market capitalisation. With a carefully designed acquisition policy, the Botìn family has been pushing Santander to the top of the rankings. While I’m bullish on the banking sector, I’m particularly bullish on Banco Santander, as I believe the bank to be well positioned for the future and to have benefited from the crisis.

Comments (0)