How to be a contrarian investor – and why!

Successful investing is not meant to be easy. Human beings are not evolutionarily well adapted to be good at investing. But after allowing for the psychological challenges involved, and not least the patience required, there are some basic principles that will stack the odds firmly in your favour.

The most terrifying and important test for a human being is to be in complete isolation. A human being is a very social creature, and ninety percent of what he does is only done because other people are watching. Alone, with no witnesses, he starts to learn about himself – who is he really? Sometimes, this brings staggering discoveries.

Because nobody’s watching, you can easily become an animal: it is not necessary to shave, or to wash, or to keep your winter quarters clean – you can live in shit and no one will see you. You can shoot tigers, or choose not to shoot. You can run in fear and nobody will know. You have to have something – some force, which allows and helps you to survive without witnesses.

Once you have passed the solitude test you have absolute confidence in yourself, and there is nothing that can break you afterward.

– John Vaillant, The Tiger

John Vaillant’s The Tigeris a gripping read. It is set in far eastern Russia, in a wilderness that the Chinese call the “forest sea”. It tells the true-life story of a trapper and poacher, Markov, who is killed by a tiger. It goes on to tell the story of a unit called Inspection Tiger, which is brought in to investigate Markov’s death. To a certain extent, it is a “murder mystery written in snow”. It is also a study in human psychology.

| First seen in Master Investor Magazine

Never miss an issue of Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

Being alone is nothing new for contrarian investors. Contrarian investing requires that the practitioner stands alone from the crowd. The fundamental problem with contrarian investing is that human beings are hardwired to be social animals. Being alone is not an evolutionarily developed skill. We would not be here if our ancestors had lived in isolation, because they would have quickly died out.

But then we are not evolutionarily prepared for the stock market, either, or for financial markets more generally. Stock markets have only been with us for a few hundred years. Homo sapiens, on the other hand, has been around for roughly 300,000 years. So our brains are struggling to catch-up with this sudden innovation in investment.

Nevertheless, contrarian investing requires that we consciously live ‘alone’ for much of the time, at least as far as our portfolios are concerned. Nobody ever got rich following the herd, except as a result of wild good fortune. But being ‘alone’ is psychologically uncomfortable. Nothing about successful investing is particularly easy – or we would all be rich. Contrarian investing requires that we live in a domain well outside our natural comfort zone. It is difficult – but then so much of what is valuable in life is meant to be difficult. Challenge creates value. As the American writer and mythologist Joseph Campbell puts it, “The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek.”

The notion that successful investing is difficult is only reinforced by the extraordinary performance of last year’s markets. As far as I can tell, the only stock market that gave investors a positive return in 2018 was that of Qatar. And their economy was being blockaded by Saudi Arabia. Go figure.

So contrarianism (or value investing, which is practically the same thing) is not easy to practise. Another thing which is notoriously difficult for most investors – whether private or professional – is patience. The famed Canadian value investor Peter Cundill archly observed that:

The most important attribute for success in value investing is patience, patience and more patience. THE MAJORITY OF INVESTORS DO NOT POSSESS THIS CHARACTERISTIC.

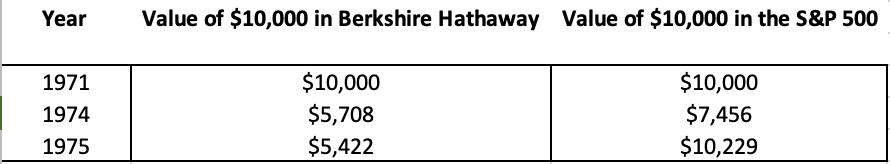

A case in point. The US investor and blogger Morgan Housel suggests that the best preparation for the next bear market is not to hypothesize your response, but rather to recall how you actually reacted to the last one. So here’s a trial run. The table below shows how an investor in Warren Buffett’s holding company, Berkshire Hathaway, would have fared during the 1970s. Imagine you are a shareholder. You have followed Buffett since he established his first investment partnership in 1956. In 1971, you invest $10,000 in Berkshire Hathaway stock. The table shows the value of your shareholding versus an investment in the S&P 500 stock index.

So a simple question: Would you have sold?

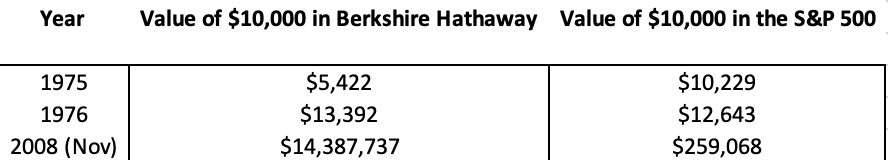

Now that you’ve had a chance to consider honestly, let’s unfurl the calendar a little further. Here’s how history played out.

Be honest. Would you have sold?

In a fabulously ironic twist of fate, by 1975, not only had our putative Berkshire Hathaway investor incurred a loss of nearly 50 percent on his shareholding, but the stock market as a whole was comfortably back in the black. I think many shareholders would have bailed on Buffett back then. And they would, of course, have missed out on quite extraordinary gains had they done so. Successful investing simply isn’t easy.

Berkshire Hathaway, of course, is a completely different animal today versus what it was in the 1970s. As Buffett himself has well observed, the tree doesn’t grow to the sky. When Buffett purchased the company, its share price was around $19. The stock has never split. As at early January 2019, Berkshire stock was trading at $294,000.

| First seen in Master Investor Magazine

Never miss an issue of Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

There are clearly two ways of going about successful value investing. One is to put in the hard yards yourself. The other is to delegate that task to a professional fund manager. And it is, of course, possible and probably desirable to combine the two. I enjoy the intellectual pursuit of stock picking, but I also enjoy hunting out like-minded managers, especially in parts of the world where I have nothing to bring to the table by way of market knowledge or affinity.

Per Berkshire Hathaway, however, it is also critical to discriminate between asset managers and asset gatherers. With no disrespect towards Warren Buffett, his best days as an investor are behind him. This is not a judgment call but simply mathematics. As Buffett himself has acknowledged, it is far easier to generate high returns when you manage a small fund than when you manage a colossal fund. As he says:

Size is the anchor of performance. There is no question about it. It doesn’t mean you can’t do better than average when you get larger, but the margin shrinks. And if you ever get so you’re managing two trillion dollars, and that happens to be the amount of the total equity valuation in the economy, don’t think that you’ll do better than average!

(The asset ‘manager’ BlackRock, by way of example, currently has over $6 trillion under its ‘management’.)

From the generic to the specific. Here are the criteria that my own firm uses in its search for compelling value opportunities from the world’s stock markets. On the (non-casual) presumption that we have identified company managers who are principled, shareholder-friendly people and who are also adept at capital allocation, we then seek the following quantitative characteristics from that company’s shares. We require that the price-to-book ratio is no higher than 1.5 times, and ideally below 1. I acknowledge that price-to-book is an imperfect metric in a world in which so much value is attributed to intangibles (as in the world of information technology and software, for example) but we have to start somewhere.

We also require that the price-to-earnings ratio is no higher than 15 times. We seek a cash flow from operations yield of more than 10 percent per annum (this is calculated by assessing the cash a company generates versus the total value of its debt and equity). We require that cash from operations has grown over the prior five years. (We focus on cash generation because it is more difficult to ‘abuse’ by creative accounting than either earnings or profits.) We also require that return on equity has been above 8 percent, on average, per annum.

In light of last year’s uniformly poor performance from stock markets, we derive some comfort from investing in companies where the underlying cash flow generation is doing splendidly. Whatever happens to the stock price in the short term is frankly for other people to worry about. As long as the companies themselves are performing well, we lose no sleep at night.

Welcome to the cave.

Comments (0)