How to Diversify Your Dividends

As seen in the latest issue of Master Investor Magazine

As a dividend-focused investor I am of course looking to buy companies with a good yield and a sustainable and preferably growing dividend. However, I am also very much aware that dividend cuts and suspensions are a fact of life. I can try to avoid them by sticking with relatively defensive companies, but in the long-run it is inevitable that some of my holdings will reduce their dividend.

So what is a dividend investor to do? The first line of defence is to stick with companies that are more likely to sustain or even grow their dividend. In my case this means looking for companies that are well established, have little debt, good profitability and a good track record of dividend payments, among other things. But an equally powerful weapon in the war against dividend cuts is diversification.

Although diversification doesn’t reduce the risk of a single holding carrying out a dividend cut, it can seriously reduce the risk that a cut will occur in a portfolio’s overall dividend. After all, investors shouldn’t really care too much about what happens with the dividend of any one holding; instead they should be focused primarily on their portfolio’s total dividend income, and on that front diversification has much to offer.

In order to reduce a portfolio’s overall dividend risk, a portfolio’s diversification strategy needs to encompass more than just how many stocks it holds. The underlying companies should also be diverse in terms of what they do and where they do it, and in the rest of this article I’ll explain the rules I use to manage every aspect of my own portfolio’s diversity.

Diversify across lots of different companies

Having a relatively large number of holdings is probably the most obvious feature of a well-diversified portfolio. However, holding lots of different companies is simply a means to achieving the true end, which is to keep the size of each holding relatively small. For example, a portfolio with 30 holdings may sound diverse, but if one holding takes up 90% of the portfolio then in reality it isn’t diverse at all. So rather than focus on the number of holdings, I prefer to focus on the size of each holding and, more importantly, the maximum size that I’m comfortable with.

Many years ago I used to have just ten companies in my portfolio, with some positions taking up almost 20% of the total. I think that degree of concentration is fairly common among private investors, but having suffered significant losses with that approach I now think such large positions are extremely risky for most investors.

The risk of losing a lot of money from a single bad investment is much higher in a concentrated portfolio, but that isn’t the only risk. Perhaps a more important risk is the impact such a portfolio can have on investor behaviour. Highly concentrated portfolios can lead to elation or worry when a single holding’s share price goes up or down, because each holding makes up a significant part of the portfolio’s total value. For most people, if a large holding in their portfolio goes down in value their natural feeling is worry and pain and their natural reaction is to escape that pain by selling. This often leads investors to sell at low valuations, which is the opposite of the “buy low/sell high” principle.

In summary then, the first goal of diversification is to reduce not only the actual riskiness of the portfolio, but also the risk that movements in any one holding will cause the investor to make a bad knee-jerk decision.

There are no hard and fast rules for what is an appropriate maximum position size, but personally I start to feel uncomfortable if a holding gets much above 5% of the total. If it hits 6% I’ll reduce exposure to that one company by selling around half of the position and in most cases that means selling high rather than selling low. With 6% as my upper limit for each position I like to start each new investment off at around 3% to 4% of the portfolio, which gives them room to grow before they hit that 6% limit. That 3% to 4% starting position means that in practice my portfolio has around 30 holdings at any one time.

For me 30 holdings is about right and provides a nice balance between diversification on the one hand and the effort required to keep up to date with each investment on the other. You might prefer to hold more or less than 30 stocks, and if you hold some of your investments in funds rather than shares then you may not need anything like as many individual stocks, but it’s still a good idea to put an upper limit on the size of any one stock.

Diversify across lots of different sectors

Holding lots of different companies is the biggest step an investor can take towards diversifying their portfolio, but it is only the first step. Having decided on a maximum size for each holding and the approximate number of holdings in the overall portfolio, it’s a good idea to think about how many holdings should come from any one industry or sector.

Sector diversity is perhaps the biggest driver of inverse correlation among holdings – in other words that some will go up as others go down. This is because some sectors are affected in opposite ways by the same economic environment. For example, low oil prices may be bad for companies that extract oil because although demand for oil may go up it might cost more to extract each barrel of oil than it can be sold for on the open market. However, if demand for oil goes up as oil prices go down, companies that ship oil around the world may see their revenues and profits go up.

In the real world the impact of the economy on each industry or sector is incredibly complicated and complex, so rather than trying to work out exactly how each sector will behave under different economic conditions I simply focus on holdings stocks from a diverse range of sectors.

As with the number of companies in a portfolio, how many sectors you invest in is a personal matter. In my case I don’t like to have much more than about 10% in any one sector, so with a portfolio of 30 stocks that works out to no more than three per sector.

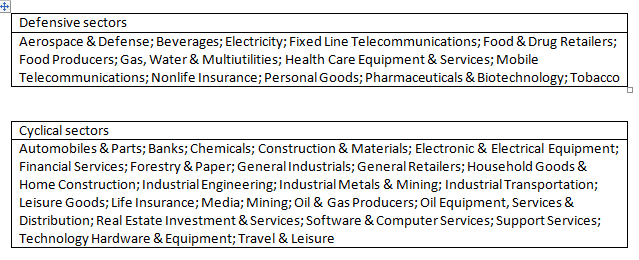

How you diversify across sectors will depend to some extent on which sector categorisations and definitions you use. I get mine from ShareScope, which uses the Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) definitions, as do many other data providers. You can see a list of all the defensive ICB sectors in Table 1 and all the cyclical sectors in Table 2. If your data provider uses different sector definitions (as MorningStar does, for example) then you’ll need to adapt your diversification rules to suit.

Diversify between cyclical and defensive sectors

As well as diversifying across many different sectors I think it’s also a good idea to control how your portfolio is split between cyclical and defensive sectors. If you’re obsessed with reducing income and capital risk then you may want to have your portfolio invested primarily in defensive sector stocks. On the other hand, if you’re willing to accept greater risk in pursuit of greater gains, then a focus on cyclical sector stocks would make sense.

I prefer the middle way and so I try to hold a more or less equal number of stocks in both cyclical and defensive sectors. In practice the exact split may not be 50/50, but generally I aim to have at least half of my portfolio in defensive sector stocks.

If you don’t use the ICB sector definitions then your data provider may categorise each of their sectors as cyclical or defensive, otherwise you’ll need to split them into cyclical and defensive using your own judgement.

Diversify across many different countries

The last aspect of diversification which I take into account is geographic diversity. I live and work in the UK and so I don’t want my investments to be overly impacted by this country’s economic ups and downs, or in fact the economic ups and downs of any one country. To avoid excessive exposure to a single country a truly diverse portfolio would generate its total revenues, profits and dividends as much from international sources as from the UK, and preferably from as many different countries as possible.

To work out the geographic spread of a portfolio you need to know the geographic spread of each individual holding, but finding that data can sometimes be a bit tricky if not downright impossible. In their annual reports, some companies will quite helpfully state what percentage of their revenues or profits came from various geographic regions, including the UK. For example, a company’s results might state that revenues are generated 35% from the UK, 50% from the USA and 15% from Germany. Other companies may simply state that 50% of revenues came from Europe and 50% from the USA, while other companies may be even more vague than that. If you look through a company’s annual report and there is no explicit mention of where its revenues or profits came from, then an educated guess is probably the best option.

One alternative to looking through annual reports is to use a data provider such as MorningStar Premium or SharePad, both of which show the geographic split of revenues and/or profits for many companies. However, their data is still based on data from annual reports and so vague information such as “50% of revenues from Western Europe” is still possible, as is the need for the occasional educated guess.

Once I have a number for the UK revenue percentage for each holding (I tend to focus on revenues, although you could focus on the geographic spread of profits if you prefer) I simply calculate the average of that value for the portfolio as a whole. That average UK revenue percentage gives me a ballpark figure for a portfolio’s exposure to the UK economy and – as a general rule of thumb – I like to keep that exposure below 50%. I invest primarily in FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 companies and for the most part they are relatively UK-focused indices, but so far I haven’t found it especially difficult to keep my portfolio’s UK exposure below 50%.

Much like any other aspect of diversification, if for some reason my portfolio finds itself with an average UK revenue percentage of more than 50%, then I’ll just make a small adjustment with my next buy or sell trade. If I was looking to sell one of the least attractive holdings (which I do on a regular basis) then I would look to sell one of the more UK-focused holdings rather than one with a more international business. Alternatively, if I was looking to buy something new then I would try to find a company where less than 50% of its revenues came from the UK in order to reduce the portfolio’s UK exposure.

None of this is rocket science, but by taking position size, industry, cyclicality and geography into account, a dividend portfolio can be made much more robust and much less risky, without necessarily reducing its potential returns.

Comments (0)