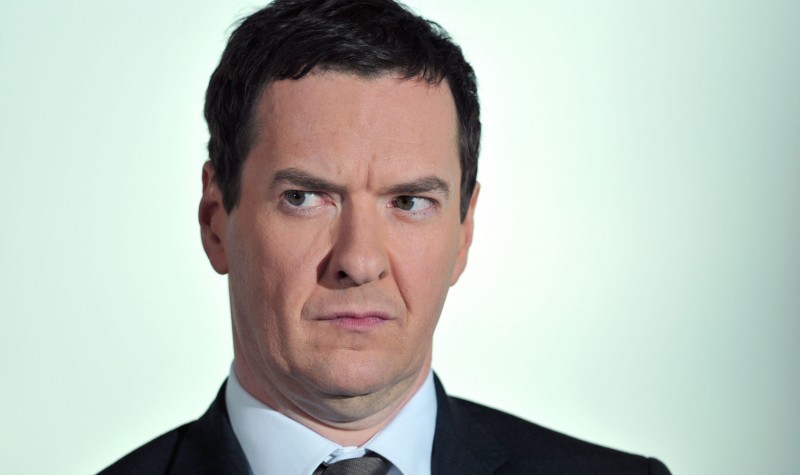

Winners and losers in Mr Osborne’s Brave New World

O brave new world,

That has such people in ’t!

– Miranda, The Tempest Act 5, Scene 1 by William Shakespeare

On 08 July George Osborne delivered the first budget from a Conservative government since Ken Clark stood at the House of Commons despatch box in March 1997. Although many of Mr Osborne’s measures had been well trailed, the final coup de grâce – the introduction of a mandatory Living Wage – came as a surprise. This will have important implications on both government finances and corporate profitability in the UK which I would like to unpack here.

The overriding economic theme of the new government is now clear: that Britain should move from a low-wage, high-tax, high-benefits economy to a high-wage, low-tax, low-benefits one. This amounts to nothing less than the dismantling of the legacy, not just of Gordon Brown, but all of those who have believed that the welfare state is the only cure for social deprivation.

If he succeeds, then this may turn out to be the most radical government since the Labour government of 1945-51 which established the National Health Service and the welfare state. When I say “radical” I mean the word in its original sense of changing direction from the course previously travelled. Make no mistake; these policies could take us somewhere very different from where we are now. We could be heading for a country with sustainable public finances and a dynamic economy.

What about Mrs Thatcher’s government of 1979-90, you ask? Although at the time it seemed that she turned the country upside down with privatisation, de-regulation and a more business-friendly tax regime, she did little to halt the inexorable rise of the welfare state. (Nor did the Iron Lady stand in the way of Ever Closer Union in Europe –but that is another conversation).

Gordon Brown introduced in-work benefits in their present form in April 2003. Despite five years of the Coalition, a full-time worker on the Minimum Wage (£6.50 per hour now, but rising to £6.70 this October) still pays income tax and NICs and then claims Working Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit, Housing Benefit and the rest.

True, the personal allowance (the amount each individual can earn without paying income tax) was raised by the Coalition from around £6,500 under Labour to £10,600 in the current tax year, meaning big tax cuts for the low-paid. Mr Osbourne expressed in his budget speech the “aspiration” that the personal allowance be raised to £12,500 before the end of this parliament. This would mean that a full time worker on the minimum wage earning (37.5 x 52 x £6.70) £13,065 would still pay income tax, not to mention NICs.

By the way, the increase in the personal allowance announced by Mr Osbourne to £11,000 next year was as planned in the March budget; though the threshold for higher rate (40%) income tax was higher than expected.

The main argument against in-work benefits is two-fold. Firstly, they distort incentives by favouring part-time workers over full-time workers and they skew marginal tax rates for those making the journey from unemployment to work. Secondly, they incentivise employers to pay low wages (but above the Minimum Wage), knowing that the employee’s income will be topped up by the government. Further, employers have little incentive to train their workers and thereby raise skills and consequently productivity.

Even Labour’s Frank Field, the Chair of the Select Committee on Work and Pensions, has argued that reform of the welfare system will be critical in addressing the country’s yawning productivity gap.

Critically, though, in-work benefits have proven an extremely costly element of a burgeoning welfare bill. As Mr Osbourne observed during his budget speech, it is rather odd that the UK, with 1% of the world’s population and which generates 4% of global GDP, pays 7% of all welfare benefits paid on the planet. According to Mr Osbourne last Wednesday, in 1980 working age welfare accounted for 8% of all public spending; today it is 13%.

The solution Mr Osborne is offering is to move to a compulsory Living Wage (estimated at £9.15 per hour in London today, according to the Evening Standard) and to freeze Gordon Brown’s expensive Working Tax Credit altogether for at least four years. This Living Wage will be introduced in April next year at a rate of £7.20 per hour for all workers over the age of 25. The Low Pay Commission will then be asked to determine further rises over the next five years such that workers receive at least 60% of median earnings by 2020. That will prospectively be £9.35 per hour by then.

Many employers will have to put up wages which will go some way to compensate workers for the loss of benefits over the course of this parliament. To reward employers for their new-found generosity, corporation tax will be reduced from 20% today to 18% by 2020.

But during the transitional period from the low-wage, high-tax, high-benefits economy to a high-wage, low-tax, low-benefits economy, some people are going to lose out. Paul Johnson of the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimates that about three million households are going to be £1,000 per year worse off[1] next year. The IFS later suggested that up to thirteen million people will lose about £260 per year.

Reduction of in-work benefits will also no doubt discourage supposedly benefit-motivated European immigrants – but not the hard-workers that immigrants overwhelmingly are.

In total, £12 billion of benefits cuts will be phased in over three four years, longer than expected, with in-work benefits and housing benefit at the forefront. Mr Osborne’s quest for a budget surplus by 2019-20 is credible; and is supported by more optimistic OBR forecasts. But just consider that even in 2020-21 our Debt to GDP ratio will still stand at an eye-watering 68.5%.

Now it is ironic that the Tories, who opposed the introduction of the Minimum Wage in the 1990s, have now championed the Living Wage. Back then, they applied market principles to the labour market where, just like in the goods market, supply and demand should determine prices (wages), thus minimising unemployment. Small businesses, they said should be allowed to pay what they could afford. Of course, sensible Tories always believed that there should be a safety net for the disadvantaged, but that the best way to help families was to get parents into work.

Mr Osborne has understood that in fact the labour market has been distorted by two exogenous factors. (Excuse the economists’ terminology).

The first is the effect of immigration. Naturally, more motivated workers in Europe’s periphery will gravitate to countries where labour rates are higher. But, if you are going to have large-scale migrations of predominantly low-skilled workers, don’t be surprised if wages fall, and rates of productivity too. Apparently, the Blair-Brown government never even considered this possibility. Everybody seems to agree that the super-rich have pushed up house prices in London; and yet it is still politically incorrect in some circles to say that mass migration has stymied wages.

The second is that the very existence of a welfare state automatically imposes a kind of floor on people’s wages since even unemployed people receive income (benefits) and state-funded social goods (housing, healthcare, education etc.). Most people would say that is as it should be. But, correspondingly, the post-tax economic advantage (marginal gains, in economist-speak) of work should be appropriately higher than the minimal lifestyle offered to those who are out of work, or who cannot work, by the state.

I have already identified three main arguments against Mr Osborne’s new paradigm.

The first is that “Living Wage” is just a euphemism for a souped-up “Minimum Wage” and isn’t a new idea at all. Whatever. It’s pointless to engage in arguments about language.

The second is that Mr Osborne is artfully passing the burden of alleviating the condition of the less well-off in our society from the public to the private sector. He would no doubt counter this by saying that business has been unfairly profiting from the tax-funded generosity of the state. A Marxist would say that business has been generating “supra-normal” profits by paying workers lower wages than they would accept in the absence of state-funded inducements. Both of these arguments amount to the same thing.

The third is that big business might be able to cough up, but micro businesses could be wiped out. And I agree that if the state systematically enforces the Living Wage in low-wage industries there may be some unintended consequences. Most of our high street takeaways – which are often family businesses run by people from ethnic minorities – will struggle to comply.

And consider that a substantial proportion of Britain’s army of nearly five million self-employed people earn less than a full time worker on the current Minimum Wage, so will fall behind even further when the Living Wage is rolled out.

But let’s proceed from where we are. For the first time in the modern era a British government has set us on course to contract the welfare state. That’s momentous. But, with our investment hats on, who will be the winners and losers?

Losers first. Companies that employ large numbers of people at or just above the minimum wage will incur big rises in their salary bills – prospectively by up to 44% (that’s the difference between £6.50 and £9.35). So, that includes retailers in general and supermarkets in particular.

Browsing through Tesco’s (LON:TSCO) report and accounts for last year, I notice that they have nearly 316,000 employees in the UK alone. Assuming that about half of those people are on the minimum wage (or near it) and assuming that half are full-time and half are part-time, I estimate that Tesco’s wage bill will increase by about £650 million between now and 2019-20[2]. For a company that lost £2 billion last year and made £4 billion this year, that’s significant.

And the winners? What about companies which employ high-value added employees and which run high-quality apprenticeship schemes for young professionals? In fact, Mr Osbourne visited BAE Systems (LON:BA) in Lancashire on Thursday morning (09 July) – just such a company. But they are not happy either, because they will have to pay into a levy to finance apprenticeships for smaller employers.

I’m sorry to say that, short-term, there are no obvious corporate winners, though the cut in corporation tax will be welcome. But, medium-term, if the UK can get its finances in order and halt the inexorable advance of the welfare state that has wrought havoc amongst our European neighbours, then we can start to cut taxes further and become a nation with prosperity for all.

So the final winner is: UK PLC, in a dangerous and uncertain world.

[1] Interview on R4 The World at One, Thursday, 09 July 2015.

[2] My calculation sheet is available.

Comments (0)