The BoE Is Walking A Thin Line

With the British economy now growing at an unspectacular but still decent pace, it is time to finally let it stand on its own. The support given by the Bank of England with near zero interest rates and asset purchases totalling £375 billion should be near an end, as the central bank is walking an ever-thinner line. More than six years after cutting its key policy rate to the current record low of 0.5%, it is time for the central bank to move on. Mark Carney is finally heading towards some action as BoE governor. While the market foresees the first rate hike occurring in one year’s time, academic research pinpoints accelerated action, as there is no longer support for the current level of (in)action.

The Taylor Rule…Once Again

In my recent articles I have often mentioned the Taylor Rule, as I tried to find some justification for current central bank policy, in particular regarding the US Federal Reserve. Allow me to revisit it once again, but this time with regard to the UK.

First of all, let me just briefly describe what the Taylor Rule is, in case you missed my past articles related to the topic. Monetary policy can either be rules-based or discretionary. When it is rules-based, there is not much scope for subjective treatment of data and policy action is relatively predictable. However, when it is discretionary we rely on the monetary policy committee’s will, as almost anything goes as long as it respects the primary goals set for the central bank. Much has been said against a rules-based monetary policy and in favour of a discretionary policy. After the Stanford economist John Taylor wrote a paper in which he describes the central bank policy rate as a function of an output gap and an inflation deviation, many arguments have been made in opposition to such a simplification of monetary policy. In fact, if what later became known as the Taylor Rule was applied blindly, we could replace Mark Carney and Mario Draghi by a set of computers which would collect the necessary economic data every month, plug it into a pre-defined mathematical relation and set the bank’s policy rate accordingly.

But when Taylor wrote the paper, he wasn’t thinking about central banks following the rule in a mechanical and automatic way but rather using it as objective guidance against which central banks should check their subjective decisions about the policy rate. That means that any deviations from the rule should be justified. This would allow for some degree of discretion in policy setting to accommodate to a varying sensibility regarding the observed reality while still keeping that discretion within some boundaries. Rules-based policy setting prevents political pressures and makes central banks more accountable for their actions. Even though no central bank explicitly assumes the use of any rule, the truth is that in explicitly pursuing some long-term inflation target while attempting to stabilise the economy in the short term, they’re implicitly acknowledging the logic of the Taylor rule.

In the original Taylor (1993) work, the policy rate is expressed as follows:

i = r + p* + 1.5 X (p – p*) + 0.5 X (y – y*)

What that means is that, in the long term when the economy is at full employment (y = y*) and inflation is equal to its target rate (p = p*), the policy rate should be equal to the long-term real interest rate (assumed to be 2% by Taylor) plus the target inflation rate (equal to 2% for most central banks). In the UK, for example, the formula results in a policy rate that should average 4% in the long-run.

While there is generalised agreement regarding the fact that the sensitivity of the policy rate to inflation needs to be higher than one (otherwise inflation or deflation would spiral into a worse problem), there is no agreement regarding the real rate of interest and the sensitivity attributed to the output gap. Taylor estimates the first at 2% and the second at 0.5; but when we use these parameters with real data we often find that the effective policy rate set by a central bank deviates from it.

There are several estimations of the Taylor rule for the US economy. But what about the UK economy? How does the real policy setting compare with Taylor’s prescriptions?

The Taylor Rule in the UK

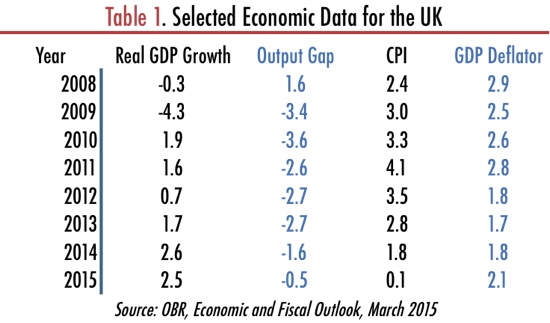

I collected some data from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) Economic and Fiscal Outlook report released in March 2015. The OBR reports an estimate for the output gap that can be used directly in the Taylor rule without any need to collect separate data for output growth and potential output. In terms of inflation, Taylor uses the GDP deflator, even though many are those who are a little more creative in that respect and use inflation measures that in the end understate the price level.

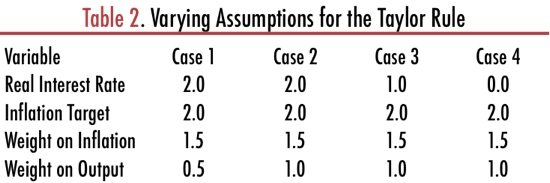

To accommodate different weights for the output gap and a lower real rate of interest than initially set by Taylor, I depict four scenarios, as described in table 2 below.

The real rate of interest for the UK has often been estimated near 2%, but given that Ben Bernanke has been claiming that the developed world may be facing a lower rate, let’s allow it to be just 1.0 (case 3) and 0.0 (case 4). In terms of weight allocated to the output gap, let’s starts with 0.5, as in the original paper (case 1), and then allow it to increase to 1.0 (cases 2, 3 and 4).

Table 3 shows the results from applying the Taylor rule to the UK economic data reported in table 1 using the output gap and GDP deflator for the varying assumptions of table 2.

The official rate set by the BoE at the beginning of 2008 was 5.5%. In light of the financial turmoil experienced in that year, the BoE cut its key rate five times in 2008, to a level of 2.0%. Further cuts were prescribed in 2009 and in March of that year the official rate was set at the current 0.5%.

If we look at the estimates from table 3 and match them with the BoE policy rate of 0.5% that came in in early 2009, we can clearly understand that it is difficult to justify the policy followed if we stick with a 0.5 weight on the output gap and with a 2% real interest rate (case 1). For such a case, the rule prescribed a massive cut in 2009 from 6.2% to 3.1%, mostly due to the deterioration in the output gap, but never to as low as 0.5%.

While having a justification to react to the crisis by cutting its key rate and keeping it at a lower level for quite a long time, the data don’t justify the cut to a 0.5% rate – at least, not in cases 1 and 2. Only when we go the extra mile of cutting the estimate for the real rate of interest can we justify a zero interest rate policy and the use of unconventional measures. In case 4, for example, the advised policy rate was 5.0% in 2008 and turned negative over the next year when the financial crisis was at its peak. With the exception of 2011, this rate was negative in every year up to 2014 when it reverted to a tiny positive number. In case 3, the rate was positive but below 0.5% in four of the five years between 2009 and 2013, which also supports the policy followed by the BoE. But in both case scenarios there is an improvement in conditions starting in 2014, paving the way for rate increases. Using the OBR forecast for 2015, no scenario still supports a near zero rate. Even under the unrealistic assumptions of a zero real rate, the Taylor rule points to a 1.7% policy rate, as the British economy approaches full employment.

The above exercise allows us to understand how extreme central bank action has been during the financial crisis. As I mentioned before, whether explicitly assumed or not, a central bank pursuing inflation targets and output stability goals is implicitly following some kind of Taylor rule. But, in the case of the BoE, the Bank may have relaxed its assumptions a little too much – something that may have nefarious consequences in the future, as investment decisions have for too long been based on a lower than natural interest rate. Nonetheless, there is no engineering left to let the numbers fit the Taylor equation. At best, the official interest rate should now be at 1.7%. The central bank is walking a very thin line and needs to move quickly, before the rope breaks. The market is overly optimistic about the time left for the first rate hike but I expect Carney to take some real action sooner rather than later.

Comments (0)