Japan Adopts Negative Interest Rates

When I woke up today I was shocked by the news that the BOJ had cut its benchmark rate to -0.1% overnight. At a time when the FED is fighting to normalise its policy and the ECB is entertaining investors to delay further QE, the BOJ decision comes as a major blow and a huge step back in a global attempt to normalise policy.

The BOJ decision to cut its benchmark rate to a negative value establishes a new record for monetary policy in Japan, as it is the first time ever that the central bank will charge high street banks to hold their reserves. The measure took the world by surprise and has been embraced by investors in Europe and the US, who took the opportunity to increase the purchase of equities during the morning, as many believe that the move will prevent the FED from hiking its key rate at its next meeting and push the ECB towards further easing.

One week ago, Haruhiko Kuroda (the BOJ governor) dismissed the possibility of cutting rates to a negative value. However, he had previously hinted that the central bank should be prepared to “act decisively” to get rid of the deflation mindset that has been haunting the country for fifteen years, thus reinforcing the central bank’s determination to push inflation to the 2% level in the near term, using all tools available. In fact, in terms of creativity and determination, central bankers rank high, as they appear unrestrained in their attempt to boost global asset prices.

After being elected in December 2012, Shinzo Abe adopted several measures to revive the Japanese economy and finally lift it from its two-decade stagnation. From day one of his premiership, Abe pressed the BOJ to adopt a bolder monetary policy that could help dismantle the entrenched low inflation expectations that had taken root in Japanese minds over the years. Only bold action could be disruptive, as past mild intervention serves as evidence that small increases in monetary easing aren’t enough, according to Abe. In April 2013, the BOJ decided to expand its asset purchase programme by 60-70 trillion yen a year. In October 2014, faced with weaker growth caused by an increase in consumption taxes, the BOJ further expanded its programme to 80 trillion yen a year.

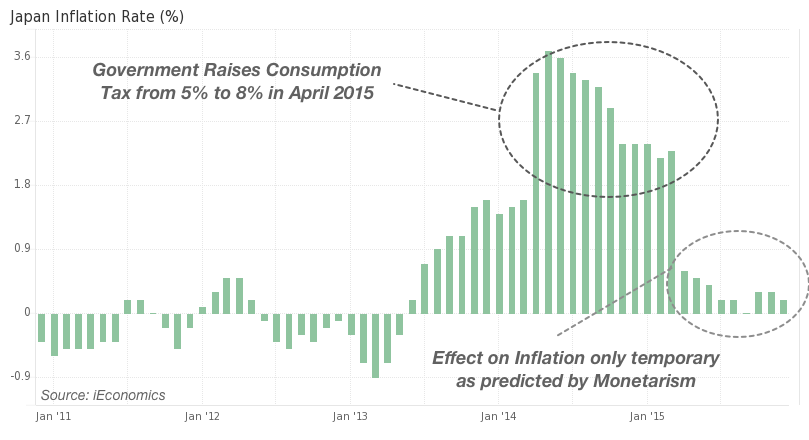

Just one year later, and at a time when the global monetary order was reverting to a new cycle, the BOJ further deepened its expansionary policy status, this time changing from a quantity target to a rate target. Three years into Abenomics and nothing seems to be working as desired. In fact, since Shinzo Abe took office the best period for the Japanese economy, in terms of inflation, was between April 2014 and March 2015, which coincides with the introduction of a hike in consumption taxes from 5% to 8% in April 2014. But such a revival of inflation wasn’t the result of higher inflation expectations but rather the result of an administrative hike in prices – one that would raise the price level permanently but only have a temporary effect on inflation, just as the monetarists predicted many decades ago.

Of course one could blame the monetarists for failing in their prediction of an increase in inflation as the result of quantitative easing – but the main problem is that the money is not flowing to consumer products but rather to equities and bonds. While consumer prices have been increasing at less than 2% per year, equity prices have been increasing at a pace of 22.3% per year (as measured by the Nikkei 225). In the period between 2013-2015 the Nikkei index rose 83%, mainly as a result of quantitative easing.

If equity prices were taken into consideration alongside consumer prices, the monetarist predictions would be completely validated. The problem is that central bankers act blindly in pursuit of their consumer inflation targets, using any means necessary, which is the main reason why they create so many imbalances. Recent research on monetary policy has begun to recognise that the key may be in asset prices and not in consumer prices. According to Borio and Lowe, “while low and stable inflation promotes financial stability, it also increases the likelihood that excess demand pressures show up first in credit aggregates and asset prices, rather than in goods and services prices.” If that is that true, why insist in inflation targets?

The decision taken overnight has several drawbacks. First of all, it was taken by a tiny 5-4 majority, while the pace of asset purchases was held unchanged by an 8-1 vote. This is a sign of weakness, meaning that Kuroda wasn’t able to persuade a significant majority inside the policy committee. Secondly, this move comes at a time when other central banks were already looking ahead to higher rates. Markets have been reacting positively, much because investors believe such measures would delay the FED in hiking again and push the ECB into further easing. While it may be easy to think of this as being positive, I believe this may further exacerbate financial imbalances instead of pushing prices higher. Thirdly, the moves may be seen as a solution of last resort taken by a central bank running out of firepower. In a country where the central bank owns government paper amounting to 80% of GDP, investors may believe the BOJ has reached the limits of its capacity and effectiveness with its asset purchase programme. Fourthly, I believe this move may further press prices down. While it may sound odd for many readers, the truth is that Japanese households hold a significant part of their wealth in bank deposits and government bonds. In cutting rates, the BOJ is helping to erode yields on bonds and may urge banks to cut deposit remunerations (or tax them). The final effect would be a decrease in the value of savings and then in financial wealth. I really can’t see how a “poorer” household is expected to increase consumption. This is likely to happen because, at this point, I believe the effect of monetary policy on savings is greater than it is on credit portfolios. Thus higher rates could be more beneficial for consumption than lower rates at this point. That’s why Japan will never go out of its current deflation stance. The currency wars are on… again!

Comments (0)