Is now the time to buy European equities?

The ECB has kept its key rates and asset purchasing programme unchanged while Mario Draghi promised investors there’s more to come in the near future. A dovish Draghi is keeping investors entertained while buying him some time to convince the other committee members to extend the current asset purchase programme. If he doesn’t deliver there will be massive disappointment. But, nevertheless, the economic and market fundamentals are currently good, providing a safety net for investors who want to enter at discount prices.

The Eurozone at the end of 2014

Let us rewind to January 22 of 2015. After so much pressure on the ECB to act in the same way as the FED, BoJ and BoE, Draghi finally convinced other policymakers and announced the European version of quantitative easing. The programme expanded the existing asset purchase programme to include bonds issued by Eurozone central governments, agencies and European institutions. It was expected to start in March and to be carried out until September of 2016, targeting combined purchases of €60 billion per month. The total amount of assets to be purchased would be €1.1 trillion. The programme was far smaller than its US counterpart (which totalled around $3.7 trillion) but was still of a considerable dimension.

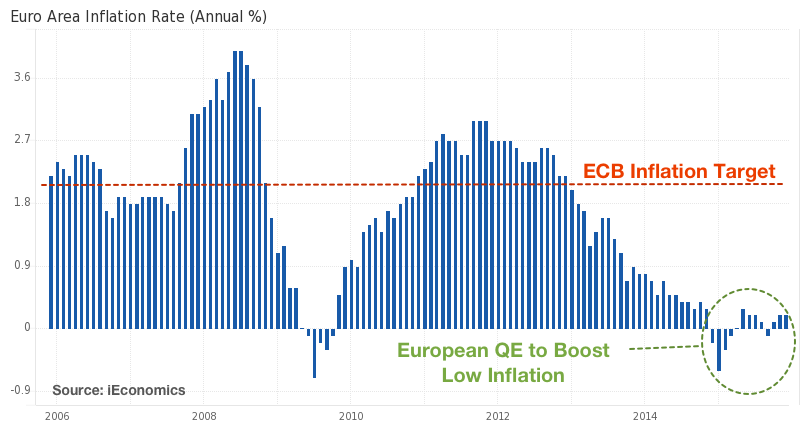

By January last year, the Eurozone economy was treading water and the central bank’s long-term inflation goal was turning into a mirage far from reach. With most European governments tied up with austerity programmes, the pressure on the ECB to do something was immense. By then, the Eurozone was facing its worst period in terms of price developments, as inflation readings for November, December and January were +0.3%, -0.2% and -0.6% respectively (YoY changes).

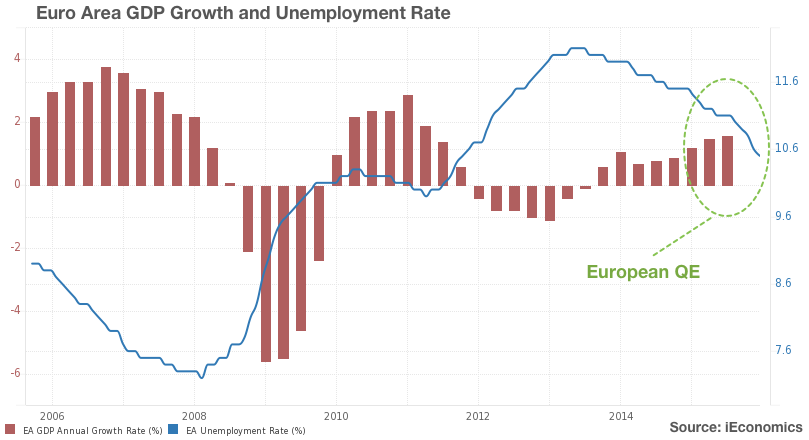

The ECB was able to drive inflation higher in the aftermath of the financial crisis imported from the US; but with all European governments tightening at the same time, the unemployment rate started climbing, which dented consumer spending and pushed prices lower again. The huge austerity experiment led the Eurozone into a double dip and pressed the ECB to act. In fact, from the very beginning of the crisis, the central bank adopted several measures that were aimed at enhancing credit support in the Eurozone and at reducing speculation on sovereigns (and helping governments improve their finances through reduced interest payments). But those measures weren’t enough to spur growth, lower unemployment, or boost prices. Just before announcing the extended asset purchase programme, the ECB was reading sluggish GDP numbers – 0.7% in Q2 2014, 0.8% in Q3 and 0.9% in Q4. While not pointing to recession, the numbers were still pointing to very weak economic conditions. The numbers coming from the jobs market weren’t much better either, with the unemployment rate sitting at 11.4% in December 2014, down from a peak at 12.1% in May 2013 – a tiny improvement.

While I am not an advocate of asset purchases, I recognise that something needed to be done at the end of 2014 because the Eurozone’s economy was stagnating at high unemployment levels.

The Eurozone one year later

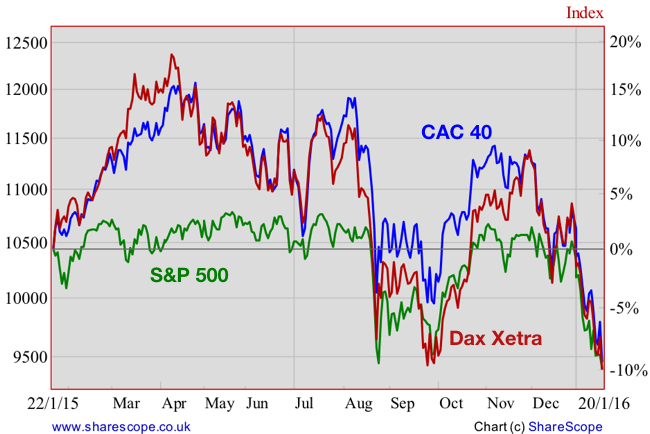

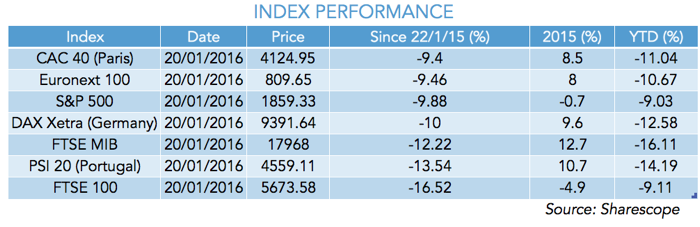

One year later, things have changed somewhat. First of all, the equity market has not really benefited from QE. Interestingly, and unlike what happened in the US, European markets are currently down near 10% since QE was announced one year ago. With a central bank purchasing massive amounts of sovereign debt, one would expect a significant rise in prices and a decline in yields. The effect should filter through to the equities market and push prices higher. In relation to the QE announcement date, the German DAX was up 19% in April 2015. At the beginning of the programme equities were flying high in Europe, but then the shortfall with the S&P 500 was filled during the rest of the year. In August, when bad news came from China, volatility increased and European markets were hit hard. Then in December a new story started. This time it was the ECB (first) and the FED (second) that produced the incentive for an equity collapse. Investors were waiting for an extension on European QE and an expansion in monthly purchases, but the ECB under-delivered at announcing just an extension of six months (to March 2017) without touching monthly purchases. With the FED hiking its key rate later that month, everything was conspiring against equities. Investors turned bearish and losses accumulated fast.

What about fundamentals?

A key question arising is: Do fundamentals justify the current downtrend?

It’s undeniable that the lack of an expansion in the QE programme was a major blow for investors. Still, more than €600 billion has been injected into the market over the last 10 months, but the Euronext 100 is down 9.5%. With Draghi pointing to a potential QE extension in March, European equities seem to be at a good entry level, as they have yet to benefit from QE and have always enjoyed much more conservative valuations than their US counterparts.

But let me push some fundamentals to the table before getting too excited. The global economy is not at its best. China has just posted GDP growth of ‘just’ 6.9%. Some emerging markets are in deep trouble – particularly those that used to make a living from oil (and other commodities as well). But, nevertheless, the European economy is not that bad. The latest GDP figures point to an annual growth of 1.6% – double what it was 1 year ago – the unemployment rate has improved to 10.5%, and inflation now sits at a tiny but positive 0.2% level. There’s certainly much left to do, but when comparing with last year, the Eurozone economy has improved significantly while the equity market has run in the opposite direction. Something doesn’t add up.

A changing picture

The need to bail out a rotten banking system and, at the same time, to sustain fiscal deficits drove Europe into chaos. With the ECB operating at the zero lower bound while sluggish growth was threatening to push inflation further below the ECB target, there were not many solutions left to the central bank besides unconventional policy tools to accomplish its inflation goal.

Frankly, I’m not a QE advocate, because I believe that it may drive asset prices above fundamentals and create a bubble that often ends in a crash. Too much QE is like an intertemporal exchange between present and future growth. By the same token, I’m also not a spend-today-and-pay-tomorrow advocate regarding fiscal policy. I believe that extreme policy leverages the economy to unsustainable levels, which is the root of the boom-bust cycle that we have been experiencing over recent decades. But I’m also wary of repairing government finances in times of crisis. Austerity measures applied in a depressed economy don’t work well.

The European experience serves as evidence that austerity measures in times of crisis can only create more economic trouble and lead the economy towards a deflation spiral. Government finances have not been repaired. No one can save when everybody wants to save at the same time. The scenario started improving only after the ECB stepped in to sustain sovereign bond yields. In 2012, 10-year government bonds were yielding around 7.3%, 14.6% and 3.7% for Spain, Portugal and France respectively. The figures are currently 1.8%, 3.2% and 0.9%. The savings in interest payments allow governments to reduce expenses and to implement more accommodative policy to spur growth again.

One year after the announcement of QE, the European political landscape has changed dramatically: in Portugal a new government has emerged and elevated growth and employment to the top of its priorities; in Spain a new government is still to be formed but a break with past austerity is also likely; France shows an increasing tolerance towards government spending; Italy has just approved a defiant expansionary budget where stimulus measures amount to €30 billion; and Angela Merkel is becoming ever more unpopular while losing influence at the European level. All this is leading to higher consumer spending and to a continuing improvement in the Eurozone economy. While everyone is waiting for Draghi to deliver over the next ECB meeting, I’m happy with the big picture: the Eurozone shows improved fundamentals and is benefiting from ever lower oil prices. I believe that European equities will fill this gap, as they seem undervalued.

Comments (0)