Iceland re-opens its door to capital flows

While Europe is recovering from the financial and sovereign crises at a very moderate pace, Iceland seems to have completely reversed one of the worst banking crises ever seen, where three banks with assets in excess of 10x the country’s GDP suddenly collapsed. Almost 10 years after the peak of the crisis, when the central bank had to impose capital controls to avoid a massive outflow of money, the country has now returned to free capital movements. While nine years ago capital outflows were a problem, today the central bank would be happy if some money exited the economy, which may be overheating.

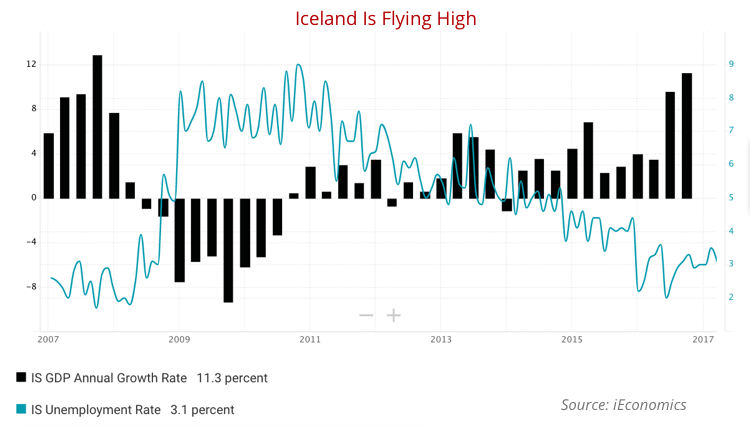

But, with interest rates at 5%, unemployment at 3.1%, and the economy growing at an annual pace of 11.3% (4Q 2016), why would investors want to take their money out of Iceland? While the central bank is imposing some restrictions to stem hot money flows, I doubt the Icelandic krona will decline over the year, in particular at a time when the Trump reflation trade is losing momentum and looks more like a mirage than like a real thing.

Many in the UK and the Netherlands have mixed feelings regarding Iceland because of the decisions taken in 2008-2009 by the government of Iceland to allow the country’s three main banks to collapse and at the same time create three new banks to save just the domestic assets. While the decision was certainly unwelcome outside Iceland, there was nothing the government could have done to save the banks in full, as they grew their assets to 10x the country’s GDP. With Europe and most of the developed world being very successful in fighting inflation, central banks kept interest rates at very low levels when their respective economies were growing. Investors were attracted by higher yields elsewhere, including the high interest rates offered by Kaupthing, Glitnir, and Landsbanki, the main Icelandic banks.

The large influx of money allowed the country to carry big current account deficits. No one cared about risk, as the notion had always been that banks are safe from bankruptcy. They’re too big to fail and central banks and governments always end up saving them! But that wasn’t the case in Iceland, as the government allowed them to collapse in the advent of the international financial crisis. The assets carried by these banks, as counterparts to clients’ deposits, were mostly illiquid and quickly fell in value, making the banks technically bankrupt. Any attempt to save them would lead to a massive increase in government debt and would drag the economy into decades of underperformance. Instead, three new banks were created – Arion, Landsbankinn, and Islandsbanki – to hold domestic assets, while interest rates were hiked to 18%, capital controls were implemented, and the country took loans from the IMF to try to stem the crisis.

As a result, Icelandic equities lost 95% of their value in a period of just a few months, the krona declined heavily against all majors, inflation rose above 12%, and the economy entered a recession in 3Q 2008, which lasted until 3Q 2010.

International investors with money in the country were infuriated by the decision to control flows of capital; but if such controls weren’t implemented at a time when banks’ assets were written down by 60% and when the current account showed a negative balance reaching 20% of GDP, the country would have experienced a balance of payments crisis. Chaos would have ensued.

During the last few years, the Icelandic economy has improved at a rapid pace and the devaluation of the currency has allowed tourism to flourish. In 2009, there were 464,000 tourists in the country. That number grew to 1.8 million last year and is expected to rise again this year to around 2 million, which corresponds to six times the country’s population. Tourism was worth 163 billion ISK (£1.2 billion) in 2010. By the end of 2015, it was worth 364.3 billion ISK (£2.6 billion). While exports of goods and services rose 31%, tourism rose 124% between 2010-2015. The share of tourism in exports of goods and services rose from 18.8% to 31.0% in the period, to put the sector on top of fisheries industries and aluminium production. The lower krona boosted tourism and turned a huge current account deficit into a surplus. The risk of a balance of payments crisis is today nonexistent. In practice, the risks now seem to lie at the other extreme.

Because of capital controls, institutional investors had no other option than to invest in domestic assets, which may have contributed to raise their prices and lead to some overheat. The rise in tourism led to a rise in house and land prices, in particular in the capital. On March 14, all remaining restrictions on capital flows were lifted and the krona suffered a huge loss of around 4% during a single day.

It is certainly necessary to open the flood-gates in order to allow institutional investors like pension funds to look for opportunities abroad and alleviate domestic pressures. But I really don’t know if it will play out as expected. Key interest rates in Iceland are at 5%; at the same time they are at zero in the Eurozone and at 0.25% in the UK. With the Icelandic economy looking as robust as it does, in particular when compared with its developed-world alternatives, I wonder whether capital is going to flow out or in. With growth in 2016 reportedly above 7% (for the full year) and with no signs of any significant slowing in 2017, the Central Bank of Iceland isn’t willing to reduce interest rates.

The economic asymmetry with the rest of Europe may attract money into the country. Even though the central bank has adopted some measures to reduce the country’s attractiveness to foreign capital, speculators may find a way in, while European investors may be seduced by the high-flying tourism sector. Because of this I expect the krona to appreciate from its current level of 119.3 against the euro (EUR/ISK) and 109.6 against the dollar (USD/ISK). I would only revise these prospects if the central bank cut rates or if there were a massive change in the monetary policy followed by the ECB. Until then, I believe the krona will do better than Icelandic authorities may desire. We already have confirmation of this: Goldman Sachs and other hedge funds have jumped into Arion Bank, purchasing a stake of 30% from the government.

The economic recovery in Iceland proved that its model was much more effective than the Eurozone’s alternative. In just a few years the business cycle turned positive and Iceland put the crisis behind it, in contrast to Europe where the crisis has perpetuated. But there is another important lesson. Monetary policy divergence and free capital flows are an explosive recipe. Low interest rates in Europe led to the hot money flows that ruined Iceland. While measures have been adopted to prevent that from happening again, Iceland may already be experiencing another bubble. Our monetary system allows for explosive money creation without controlling where the money flows, which seems to be dragging us from crisis to crisis. Only time will tell what happens, but for now, I believe the krona will do very well, in particular against the dollar, as Trump’s reflation trade is faltering.

Comments (0)