Central banks: Another fine mess you’ve gotten us into

The world of central banking continues to delight. This particular niche has delivered the greatest advances in economic knowledge, outputting refined new tools to improve the way our economy works. They redefined the zero lower bound, making it possible for borrowers to get a return on their debts; they turned the time preference upside down; and they created their own yield curve. In the process, central banks have been able to target prices (interest rates), then to target quantities (quantitative easing), and now to target both at the same time. Anything is possible today and investors won’t find the solution for the current puzzles in textbook economics, as central banking is now a complex mix of magic and wisdom. This week we witnessed two central bank meetings by the BOJ and the FED. Let’s take a look at the market consequences as a result of those two meetings.

The FED

The central bank kept its policy unchanged yesterday even though Janet Yellen offered an upbeat assessment of the US economy, opening the gate for a few rate hikes. Investors reacted enthusiastically to the fact they will continue to keep enjoying the same rate. But, in sticking with the status quo, it became clear the FED would most likely raise its target funds rate by at least 25bps by December. The CME FedWatch Tool shows probabilities of 51.9% for a 25bps hike and 6.5% for a 50bps hike. These numbers seem to understate the real odds, particularly given the upbeat assessment Yellen made and the current dissent at the FOMC.

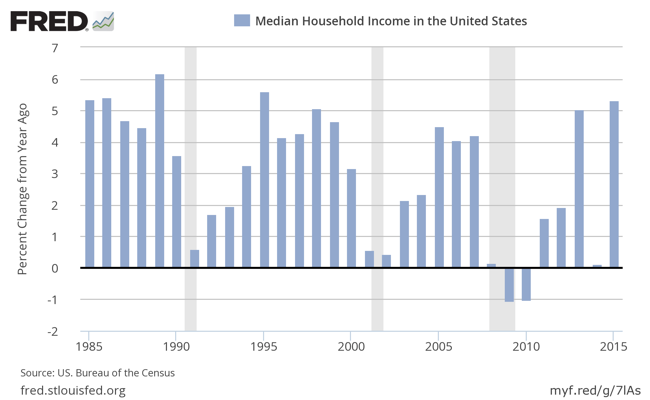

Growth has been sluggish in the first half of 2015, but Yellen stated that it is picking up in the second half. Consumption will likely pick up; as household income is increasing. The U.S. Census Bureau recently issued the Income and Poverty in the United States report which revealed mean household income rose 5.2% in 2015 while the percentage of households in poverty dropped by 1.2%.

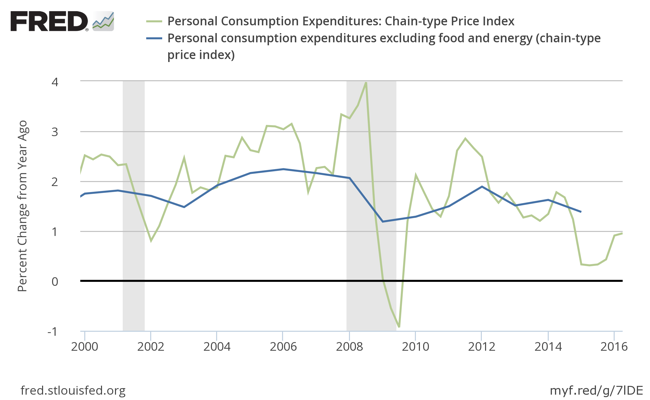

The job market has also been improving steadily with the current unemployment rate now below 5%. However, Yellen is not in a hurry to raise rates because she believes there still remains market slack. Many abandoned the job market after 2008 because they were unable to find a job, but these people are now returning. Alternative measures of inflation, taking into account not only the unemployed but those who are somewhat marginally attached or employed part-time for economic reasons, still point to a 10% unemployment rate, giving some margin for employers to hire without facing significant wage pressure. At the same time, inflation remains subdued. The PCE index, which the FED usually tracks to assess price risks, is rising at a pace below 1% and its core version, which excludes food and energy, has always remained below 2% since the beginning of the financial crisis between 2007-2008.

In general terms, the U.S. economy is doing better than OK but inflation risks are not yet mounting in a way that could make policy makers worried. Some believe that the time to start hiking rates has already arrived. On this occasion, 3 of the 17 FOMC members dissented from the committee announcement. Esther George (Kansas City), Loretta Mester (Cleveland) and Eric Rosengreen (Boston) urged for a rate hike. Likewise, 14 out of 17 policymakers now believe there will be at least one rate hike this year, making the prospect almost a certainty. As for the medium term, expectations were downgraded and policymakers now expect the future pace of rate hikes to be slower than predicted at previous meetings.

The market reaction has been positive, with the S&P 500 closing the day rising more than 1%. Gold, oil, emerging market currencies, all gained, while the dollar declined. Policy makers at the ECB and the BOJ certainly had a headache, as the economic divergences between Europe and Japan at one side and the US at the other would seem to point to the direction of rate hikes in the US.

I believe the FED is running out of time and will need to hike its key rate this year by at least 25bps. As noted from one FOMC dissenting member, there’s a risk that, at delaying rate hikes, the FED may be pressed to hike faster than desired in case inflation pressures surge. With unemployment at such low levels and consumer incomes rising, that scenario shouldn’t be discarded. I believe this may be a good time to buy the USD. I’m getting rid of any short positions on the USD.

The BOJ

Let’s move over to the eccentric, and somewhat desperate, Bank of Japan. The central bank tweaked its policy to now target the yield curve directly while keeping its target purchases under its QQE programme. I have to admit that I learned a few lessons here. I used to teach my students that central banks must choose between targeting quantities or prices, but the BOJ may have a new tool allowing them to control both at the same time, as they keep a target for asset purchases whilst pledging to keep the 10-year yield near zero. I’m really not sure how that works. On one hand, they commit to keeping a certain price and then be prepared to purchase or sell whatever is necessary to keep that price level. On the other hand, they also commit to purchase a certain level of assets…Watch this space for developments!

The worst part of all is the inconsistency between tools and objectives in policy announcements. I used to teach my students about the yield curve, explaining how its particular shape may reflect future economic conditions, and then the expected future path of short-term interest rates, plus some term premia. The BOJ set its short-term rate at -0.10% and the 10-year yield target at 0%. With a non-negative term premia, this means that the BOJ expects the short-term rate to remain near 0% for the next 10 years. At the same time, it expects to overshoot the 2% inflation goal. How is that even possible? I can’t come to a calculation where a 2% inflation target fits inside a 0% short-term rate, unless the new long-term natural rate of return is -2%. But, that being the case, we would have a major distortion in time preference, which would be well described by:

I’m willing to exchange 100 units of present consumption by 90 units of future consumption, or put another way; I’m willing to exchange a certain amount of something today by an uncertain inferior amount of that same thing tomorrow.

It seems odd to me, but again, I could be wrong. In a world where central banks set the short-term interest rates while additionally committing themselves to target long-term interest rates, they become the owners of the yield curve and, as such, they can do whatever they want with it. In the end, the yield curve reflects their will, which may completely differ from economic conditions.

In my view it would be much better for central banks to start thinking in raising its 10-year yield target to something between to 2% — 2.5%. It would certainly mean selling assets but at the same time would be more consistent with price growth. It would benefit the savings of an ageing society and free up money for present consumption.

The BOJ new target is aimed at protecting banks from further erosion of profits due to short-term negative yields but no longer seems credible. Nevertheless, I’m keeping my long position in USD/JPY and in Japanese equities, with the reason being the increasing need to hike rates in the US, more than the eccentric actions taken by the BOJ.

Comments (0)