Bond Mini Crash Uncovers Rising Risks

In my blog Don’t Fight The Fed, Fight The ECB, published last week, I said that investors face an epic opportunity to short bonds, as the risks of doing so are very narrow while the upside potential is huge.

Buying an asset just because you believe someone else will buy it from you at a greater price may work for some time, but not forever. Such a business model relies on the exact same assumptions on which the housing boom was based before the financial crisis. But prices just can’t rise forever without reflecting the intrinsic value of the underlying asset. As we have learned from the past, when prices diverge too much from intrinsic value, they become vulnerable to a crash.

At the beginning of this year, investors, seduced by the ECB bond purchasing programme, forgot about the fundamentals that drive bond prices in the long term and jumped into the market, in expectation that the ECB would purchase from them at higher prices. While the enthusiasm was high, investors were seeking higher risk debt with longer maturities and treating everything as if it was a whole single issue. The lower limit for a government yield issued by a high grade government like Germany was put at the deposit facility rate of -0.2%, as investors thought the huge purchase programme the ECB had in mind would lead the central bank to buy anything up to that limit, no matter how long the maturity was. But the ECB is not purchasing unlimited amounts, nor is it purchasing bonds forever, and sooner or later these bonds need to reflect inflation expectations. We should not forget that one of the aims of the bond purchase programme is precisely to generate inflation. So, with the pursuit of price stability being the sole mandate of the ECB, this would suggest an inflation target of 2%; at buying German 20-year bonds yielding 0.7%, one is either irrational or is simply assuming the ECB will fail miserably in driving inflation higher. In my view, while there is justification for a short-term yield to be lower than the 2% ECB target for inflation, it is not reasonable to assume the same for a 10-year or a 20-year bond.

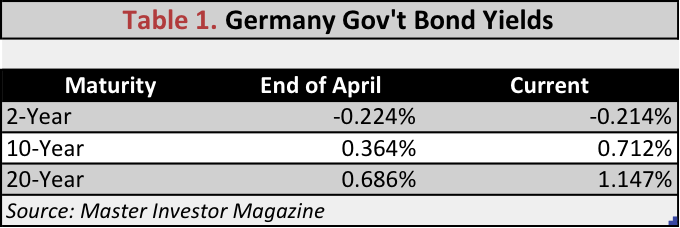

On 1st May, when the aforementioned article was published, the yields on 2-year, 10-year, and 20-year German Bonds were -0.224%, 0.364%, and 0.686% respectively. But in a matter of just a few days they rose dramatically, as you can see from table 1 below.

Rising oil prices and a quick drop in deflation fears sparked a bond sell-off, as investors realised that the rally had gone too far. Just to put this in perspective, $1.8 billion was liquidated from funds that track global corporate bonds in just five days, which is a record amount.

When yields are as low as they are, investors tend to seek longer maturities to get a decent return. The yield on shorter maturities in Europe has been negative, which means an investor is paying for the ‘privilege’ of lending money. Even though that could be rational if deflation were an issue and if an investor could not keep the money uninvested for free, investors start looking at longer maturities as substitutes while also expanding their investment horizons. Still, a 20-year German bond was offering just 0.686% at the end of April. In terms of fundamentals, to invest in such a bond you need to believe inflation will on average not surpass that level for the next 20 years in Germany, which is quite a belief!

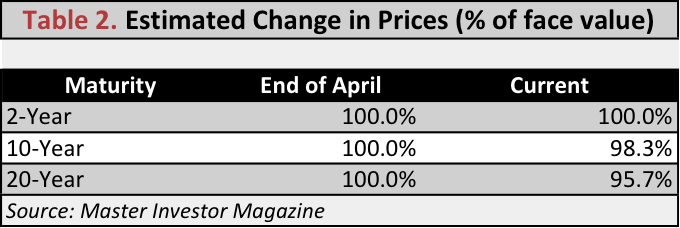

The biggest problem derived from investing in longer maturities is that these are the most sensitive to increases in the opportunity cost of holding bonds. If the ECB succeeds and inflation starts rising, the loss an investor can take on longer maturities is massive when compared with the shorter maturities. For example, let’s say you purchase a 2-year and a 20-year bond, with both paying semi-annual coupons, currently trading at par and yielding 0.5%. If inflation expectations suddenly rise to the ECB long-term 2% objective and the price of both bonds follows such a rise to reflect a 2% yield, then the shorter maturity would trade at 98.5% of face value while the longer-maturity would trade at 86.5%. The loss in the 20-year bond is huge when compared with the 2-year bond.

Table 2 above reflects the same reasoning of the given example but using the real data from table 1. The change in yields observed during the last few days resulted in significant losses for the 10-year and 20-year maturities. Investors were seeking a bond yielding around 0.7% per year but have lost almost 5% in a few days. This clearly exemplifies the risks of being long in the bond market. Those purchasing bonds now are likely to lose money over time, either buy selling them at a discount or by losing purchasing power at maturity.

Comments (0)