Are Bonds Now Way Too Risky?

The traditional perception is that bonds are a safer investment than equities. But is this a fallacy? Over the short term equities incur in a huge price risk; but over the long term bonds may very well struggle to perform as expected. In times of extreme central bank intervention, this issue regains life and needs to be considered, in particular by those trying to save for retirement. Bonds may be much riskier than believed…

If you haven’t had the opportunity to do so already, I invite you to take a look at the latest edition of Master Investor Magazine, where we discuss the greatest challenges we (and in particular the Millennials) currently face in terms of retirement. With the world submerging into a state of low returns, it is becoming increasingly difficult to save enough to retire comfortably, if to retire at all. To fight an epic recession, central banks have pushed interest rates to record lows and haven’t been able to revert their policy to a more normal state as yet.

Central banks are struggling to find ways to reflate the world economy. While low inflation (or even deflation) should not hurt your retirement savings (it should allow you to purchase the same for less), low interest rates do hurt your savings, as they force you to either save more or accept a later and/or less affluent retirement. Some would say that in a deflationary world a low interest rate still translates into a positive real return. While that may be true in the short term, it would most likely not be the case in the long term. Central banks are trying to force real interest rates into negative territory and they have been so committed in pursuit of that goal that inflation will pick up at some point and erode the real rate of return. This may not sound worrying to those speculating in bonds, but it is frightening for all those trying to achieve a comfortable retirement through their lifetime savings. It is common for savers to allocate a large proportion of their savings to bonds; but under current economic conditions, that may be the equivalent to shooting oneself in the foot. Investing in bonds is the riskiest business one can engage in at this time. Over the long term it is a bet against central banks: one that challenges the ability of the central bank to boost inflation towards, at least, their statutory goals.

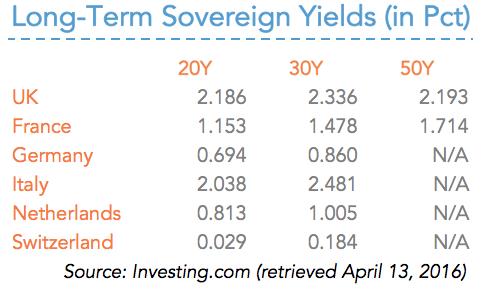

Because everything else has failed so far, the ECB is now not only pushing its deposit rate into negative territory but also purchasing assets on a large scale. Last year, Mario Draghi announced a promising asset purchase plan amounting to €60 billion per month, which included government bonds. One year later, he expanded the programme to €80 billion per month while also adding corporate bonds to the target purchases. At a time when new issues of bonds by EU governments are limited due to the fiscal tightness imposed by Brussels – and at a time when the demand for corporate bonds is limited due to the lack of banks’ demand (thanks to BASEL III) – the effects of European QE are extreme. The presence of a price insensitive entity like the ECB in a sluggish market can only end up pushing bond prices much higher. The result is a massive flattening of the yield curve, where investors are lucky to get a yield of 0.029% from a 20-year Swiss government bond issue. The situation for German and French debt isn’t much better, as 30-year government bonds are currently yielding just 0.860% and 1.478% respectively. While lower yields are in part the result of lousy economic conditions, they currently fail to correctly discount the future.

One should never forget that the ECB is mandated to pursue one single goal: to achieve price stability. Such price stability has been defined by the ECB’s Governing Council very precisely. One can read:

“Price stability is defined as a year-on-year increase in the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) for the euro area of below 2%.”

At the ECB website it is further stated that

“By referring to “an increase in the HICP of below 2%” the definition makes clear that not only inflation above 2% but also deflation (i.e. price level declines) is inconsistent with price stability.”

What does that mean to an investor? It just means that, when purchasing a long-term bond yielding less than 2%, the investor is either betting against the central bank or happy with losing purchasing power over time. I wish said investor good luck in fighting the central bank in the first case, and even better luck in keeping the same standard of living in retirement, in the second.

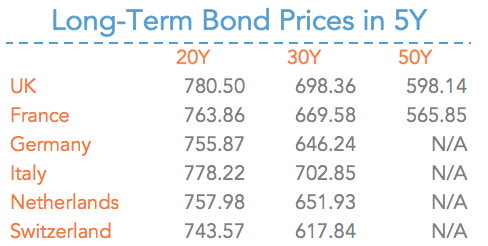

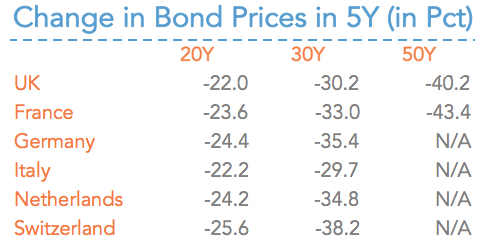

Because many short-term bonds now show a negative yield, pension funds are targeting longer-maturity bonds. But those bonds are exposed to extreme risk. When these funds purchase a 30-year French bond, they can achieve a 1.478% yield; but if inflation rises just a little bit, they will incur a heavy loss because they will be miss out on the higher yield they could, by then, attain elsewhere. A simple example helps us to understand the impact an increase in the inflation rate (and consequently in interest rates) would have on bond prices. Let’s say someone purchases one of the bonds depicted in the table above and that in five years’ time there is an upward drift in bond yields of 2%. That may seem unlikely to happen next year, but with central banks desperately trying to reflate their economies I wouldn’t dismiss that scenario in five years’ time. If that were the case, the new bond prices would look like this:

If you had purchased any of the available bonds at par, you would experience a massive loss, as depicted in the table above. The losses are worryingly high. Take the 30-year German bond for example – its price declined by 35%!

Of course you can keep the bond until maturity, but you would still lose the 2% yield you could get elsewhere for the next 25 years. That would certainly turn your retirement goals upside down.

The current bond yields don’t really reflect the future but just the fact that speculators are front-running the ECB, rushing into what the ECB promises to purchase in the expectation of then selling at even higher prices to the central bank. But what happens when the music stops? What happens to investors seeking to protect principal and to get a positive real return?

Forget what textbooks say. The price of a bond is currently given by the maximum of two components:

- A Rational Component – the present value of the discounted cash flows the bond offers, which include coupon payments and its face value at maturity;

- A Policy Component – the price the central bank is willing to pay for it, which seems to be completely independent of any rational value determined in (1).

In summary: bond price = max (rational component, policy component).

It’s not difficult to see that what determines the current price is the policy component, not the rational one. Unless you believe the ECB will keep doing this indefinitely, such policy is expected to revert during the life of a long-term bond. When that happens, valuations will revert to their rational component and the market will crash. The only way to fight against this is by keeping any of the above bonds out of your retirement portfolio and through purchasing real assets instead. Unlike bonds, those will be affected by inflation in a positive way.

Comments (0)