You Got (Almost) Everything Wrong About Our Economy, Mr Krugman

I wish our economy could be illustrated in a simple mathematical model where the increase in GDP would be a linear and precise function of the increase in something else under our control. I wish the central bank could print money for us to keep our spending habits without having to work. I wish Paul Krugman were right in his economic diagnosis and recommended treatments. But, unfortunately, there’s no simple and clear solution to our problems and I believe that Krugman got it all wrong about the functioning of our economy.

“The past 7 years have been a very good time for old-fashioned macroeconomics,” claims Krugman. Europe engaged in austerity policies as if it were the best way of creating sustainable growth, which guided many southern economies like Greece, Italy and Portugal towards disgrace. Not only were these countries unable to reduce their stock of debt; they also saw unemployment spike and GDP shrink. But, as Krugman puts it, traditional, old-fashioned macroeconomics, should have guided us in a different direction, as it long ago predicted a negative correlation between austerity and growth.

The apparent success of the US case – where the coordination between the Obama administration and the Bernanke-led Federal Reserve in adopting expansionary policies led the economy out of the crisis – is a greater source of inspiration for Krugman, who believes we should have learnt the Keynesian lesson and do the same in Europe. Just increase government spending as much as possible and GDP would start increasing again, through a multiplying effect. In the distant future we may then start thinking about paying debt back, but it is not yet the time to do it.

Despite their beauty and simplicity, the Keynesian models fail to explain why we’re heading from crisis to crisis and why these crises are ever deeper.

For Krugman it is all about saving and spending. Markets are irrational. They sometimes go up at full throttle, while some other times they go downhill and crash. This happens for unclear reasons. But when that happens spending also declines, even if for unclear reasons. Government, unlike the market, is a rational entity and should therefore do something to soften the blow. As the argument goes, we badly need households to keep their previous spending habits and should do whatever it takes to prevent them from saving. The government should then increase its spending as much as possible while the central bank should lower interest rates and eventually print some money. No matter how large the government deficit is or how low the interest rate is, one should proclaim such policies. With time, the economy would grow and by then we can think about picking up the tab for past excesses. It has always been thus and it has always worked just fine. Hasn’t it?

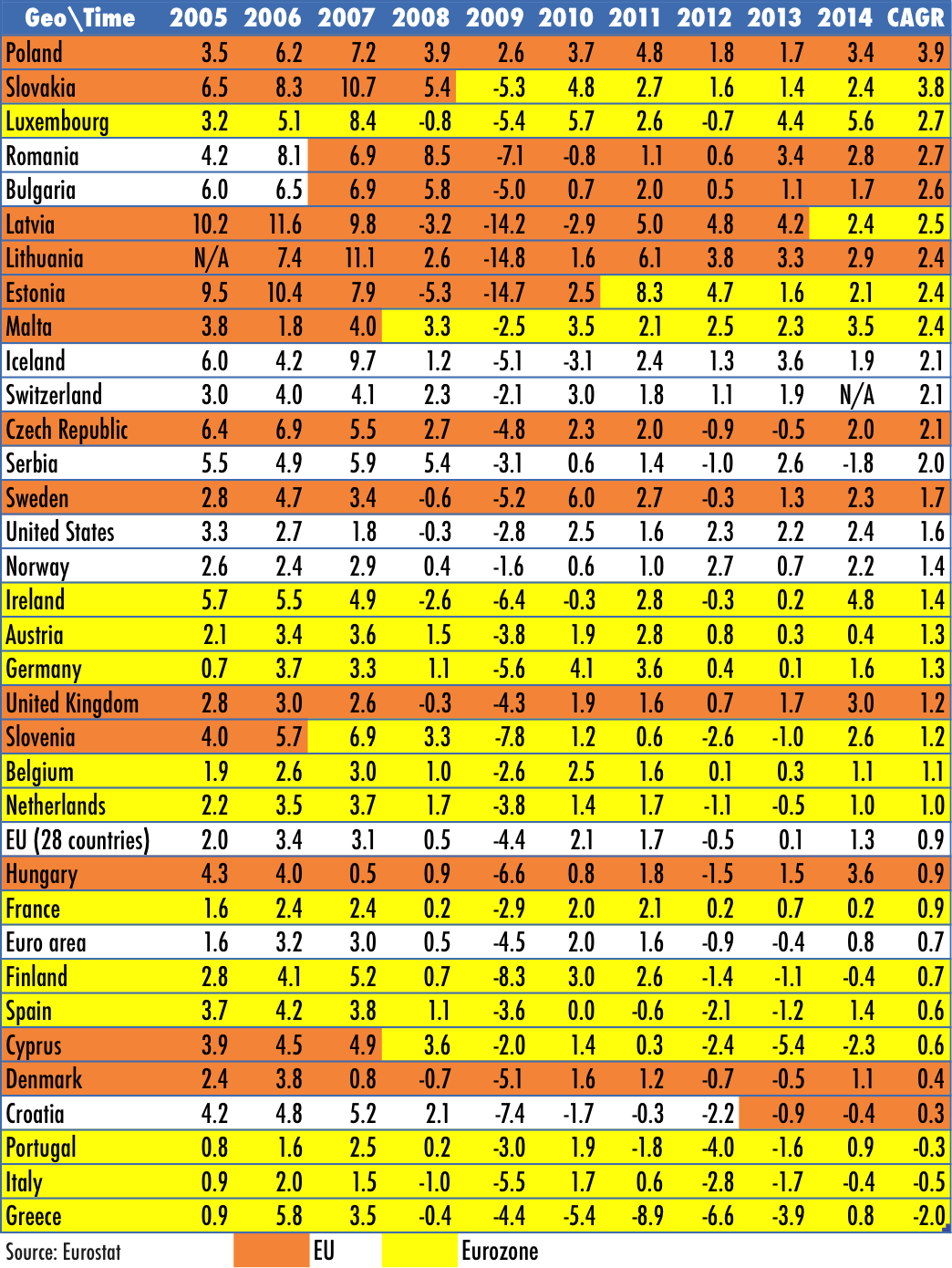

There is no risk. As Krugman points out, despite the larger deficits and huge increases in the monetary base, the yields on government bonds (and other interest rates) are still very low while inflation is subdued. That means that government spending and monetary expansion may be an old-fashioned policy, but it is the solution that we should transplant from the US and prescribe around the world. But, inspired by a few hard-nosed countries, Europe instead prescribed austerity policies, which created an army of unemployed people in Spain, Greece and Portugal, while sending most European economies into muddy waters. The situation is even worse when considering just the Eurozone countries, where GDP grew at a pace of 0.7% for the last 10 years, and there are wide differences between individual countries.

“It wasn’t at all hard to see, right from the beginning, that currency union without political union was a very dubious project” claims Krugman. He is definitely right about that. Draghi has many times pointed out that the union should not rely on the central bank to solve all of its problems. While structural reforms are needed to give the member states more flexibility in order to adjust to economic shocks, some of these shocks are so asymmetric that they require an extra adjustment tool. Had the drachma still existed, Greece would by now have allowed devaluation against the euro, as a way of restoring equilibrium. Relying solely on the adjustment of prices and wages is sometimes not enough and may lead to serious social consequences and undesired transfers of wealth. If the member states were by now politically unified, a central budget could allow for transfers of money to the most affected areas in the Union and overcome at least part of the difficulties created by the loss of the exchange rate as an adjustment tool to asymmetric shocks. I am not in favour of competitive devaluations. But, after 6 years of misery, I would say Greece is a strong candidate for a harmless devaluation.

The idea behind a central budget is that within a currency union there must be a risk sharing mechanism that allows for redistribution of money to the regions that are adversely impacted by a shock. These transfers should be rules-based and automatic. Each member state should recognise that the Union brings them some advantages and some disadvantages. In deciding whether they want to be part of it or not, they cannot decide on the basis of reaping all the benefits without giving up anything in return. Even countries that are usually net contributors to the Union, like Germany, must recognise that they benefit the most from a common market and a stable common currency, as trade represents a large share of their GDP. But of course, when such a system is in its infancy, it is not difficult to understand that, upon suffering an asymmetric shock, those who are better-off are reluctant to give up part of their revenues. That is the main reason why every rescue comes with a string of attached conditions that have no economic justification. And that is the main reason why the Eurozone is faltering. At this junction, those who are worse-off start rethinking the real advantages of being part of the Union and the only reason left for them to stay is the fear of what they could face upon leaving. That is the point at which the monetary union starts to crack. And that is the point at which the Eurozone is at.

Krugman is right in pointing out the deficiencies in integration at the EU level, which were long ago studied by Mundell (1961) in what became known as the Theory of Optimum Currency Areas. Mundell’s work served as the basis for the creation of the Euro, but was also partially scrapped by politicians pursuing their own agendas.

A common budget is needed to replace the loss of monetary policy at the country level and to ensure that there is a way of dealing with asymmetric shocks. No matter how flexible markets are and how deep the mobility across regions is, there are still asymmetric shocks waiting to occur, which need to be taken care of with a selective tool. But while the theory advises in the direction of creating a common budget, it doesn’t say anything about allowing government debt to grow forever. Austerity is a bad policy choice at this point, because it has a negative short-term impact on growth at a time when European economies are depressed.

But one cannot completely disregard the effects of fiscal expansion and rising debts on the future economic soundness of a country. Consumer spending boosted by debt is not coincident with wealth creation. Engaging in more debt doesn’t necessarily have to lead to wealth creation, and when it doesn’t it just masks the problems in the present at the cost of making them even worse in the future. The increased debt must be repaid and if no new wealth was generated with that debt, the financial soundness of the country would just deteriorate. If used like a bazooka (like Krugman often seems to advise), government spending and household debt increases may lead to a long-term deterioration in living conditions. It is possible that the financial crisis was a consequence of the Keynesian medicine meted out to past crises, which may have created a snowball effect.

But, the point where Krugman really fails to convince me is on his view on monetary policy. He believes that “the really big losers from low interest rates are the truly wealthy — not even the 1 percent, but the 0.1 percent or even the 0.01 percent”. But that seems just plain wrong to me. For that to be true, then those truly wealthy would need to park their money on bank deposits, keep their wealth as cash, and/or invest it in riskless assets like government bonds. While the richest struggle to maintain their living conditions with near zero interest rates, he argues, the middle class is investing in equities and enjoying three-fold gains… Really?

The wealthiest don’t have their money parked in safe assets. They invest in risky financial assets and real estate. These are exactly the assets that experienced a lot of inflation over the last few years, which on the one hand explains why they are richer than before, and on the other why Krugman (and the central bank) fails to see any inflation coming as a result of monetary policy. Krugman fails to see what has been an epic redistribution of wealth from the poor to the rich.

Our problem in Europe, and in the Eurozone in particular, is certainly one of lack of integration. We need a common budget and some additional transfer of sovereignty to a truly mandated European Parliament, if we are to keep the Euro alive. But we should also keep an eye on the current monetary system and understand its functioning. Money currently comes out of debt. When the stock of money is enlarged, debt is also enlarged, and the economy gains leverage. Banks are never able to repay their depositors, which means that governments need to give banks a guarantee on those deposits. But this assurance leads banks to engage in too much risk. For some unclear reasons, there is a time when consumer spending decreases. Because a fractional reserve system is a highly leveraged system by nature, when that happens, debt isn’t repaid and banks become insolvent. Then governments need to bailout their banks. It’s the same story over and over again. Expanding government spending and easing credit conditions is not the solution. It is the problem. In attempting to prop up a slowing economy, the Krugman-like models just create boom and bust cycles that massively redistribute wealth and destroy long-term growth. The austerity solution doesn’t work. The anti-austerity one doesn’t work either. First we need to stop and rethink our economy.

Real GDP growth in Europe

Comments (0)