UK inflation and what it means for your portfolio

Opinion is divided over whether the recent increase in inflation is just a transitory response to the reopening of the economy or the start of a longer-lasting trend. It is probably the single most important question for investors and has significant implications for how you position your portfolio.

Andy Haldane, who was chief economist at the Bank of England and a member of its Monetary Policy Committee until the end of June, has some interesting views on the matter. He disclosed these in a speech just before he left to head up the Royal Society of Arts.

He said that the Bank’s policy of reducing interest rates to their effective lower bound and the ongoing programme of quantitative easing (QE) had put him in an ‘uncomfortable spot’ (by the end of the year the Bank will hold close to one trillion pounds of nominal government bonds − around half of the total issuance).

His main concern was whether the continuing monetary stimulus was consistent with central banks hitting their inflation targets on a sustainable basis. In the UK the additional QE and fiscal easing both currently stand at around 15-20% of GDP, which adds significant further momentum to an already rapidly bouncing-back economy.

He is worried that when you add this to the large pool of involuntary savings amassed as a result of the lockdown − over £200bn by UK households and around £100bn by UK companies − the pent-up demand could result in rising inflation expectations:

“By the end of this year, I expect UK inflation to be nearer four percent than three percent. This increases the chances of a high inflation narrative becoming the dominant one, a central expectation rather than a risk,” he said:

“If that happened, inflation expectations at all maturities would shift upwards, not only in financial markets but among households and businesses too. This would leave monetary policy needing to play catch-up to re-anchor inflation expectations through materially larger and/or faster interest rate rises than are currently expected.”

In this sort of scenario, the central bank would have to execute an economic handbrake turn, a manoeuvre in which everyone would lose. It would mean that businesses and households would face a higher cost of borrowing and living, while the government would have to pay more to service its debt.

He is not the only one who is concerned. Mervyn King, the former governor of the Bank of England and Nicholas Stern, former chief economic advisor to the Treasury, have both criticised the central bank’s attitude towards inflation and its continued use of QE, which they said was being used to finance the government.

Higher inflation is here to stay

Kevin Doran, managing director at AJ Bell Investments, says that inflation, is, was and always will be a monetary phenomenon, created by too much money chasing too few goods: “The advent of worldwide quantitative easing programmes makes the likelihood of higher inflation a racing certainty given the scale of the stimulus.”

He says that it is different from the last bout of QE that started in 2008/09 after the global financial crisis. That time around it didn’t result in shop-price inflation because of the situation in the banking system, where the bank’s balance sheets were undergoing a period of repair:

“The process is akin to running a car. The central bank actions act as the engine of the car, but the banking system is the gearbox. For much of the period from 2008-2019, banks failed to make enough capital to repair their own balance sheets and so they absorbed much of the original QE; £253bn according to our calculations.”

This time around, the QE is being directed towards large-scale infrastructure projects and so will be felt more in the real economy, rather than asset prices. Add in a shortage of skilled labour and the resulting wage growth will transform the ‘green shoots’ of inflation into something much longer lasting:

“It is essential that investors hold real assets in order to protect themselves against the effects of inflation. This means holding any asset which generates cash flows in the future that can adjust for higher inflation, such as equity investments in companies that have pricing power. If you don’t have pricing power, you’re in trouble,” explains Doran.

One option is a property fund where the owners have the ability to increase rents at least in line with the pace of inflation. These also benefit from leverage, with the inflation eroding the real value of the debt that has been used to finance part of the purchase cost of the premises.

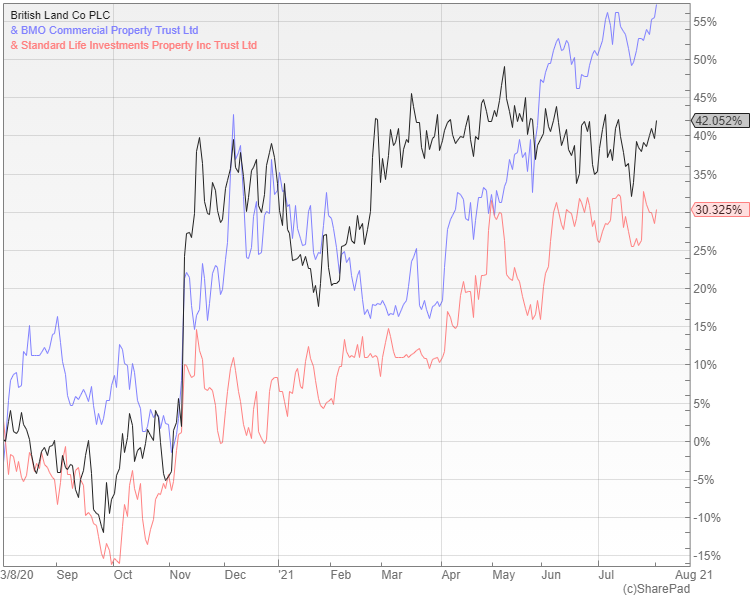

The best way to take advantage is to use one of the closed-ended real estate investment trusts (REITs) that are ideal for these sorts of illiquid holdings. Doran personally holds British Land (LON: BLND) where he says the discount to NAV is ‘bananas’, while the broker Winterflood currently recommends BMO Commercial Property (LON: BCPT) and Standard Life Investments Property Income (LON: SLI).

Too early to tell

Not everyone agrees though. Adrian Lowcock, an independent commentator, says that the current bout of inflation is being driven by short-term factors and is quite narrow. He thinks that the main drivers are temporary and unlikely to cause inflation longer term, with the current wave dissipating towards the end of the year:

“Longer term the outlook for inflation is much less clear. The disruption to global supply chains and additional precautions placed due to the pandemic could add costs now and longer term.”

There are question marks over whether the stimulus that governments have introduced is necessary and whether economies will overheat. This is more pronounced in the US, while in the UK a combination of the pandemic and Brexit is leading to staff shortages for employers, particularly in the hospitality industry, which could contribute to inflation:

“My expectation is that we could see higher inflation over the next few years once this initial spike is over, but investors need to prepare for both scenarios as it is too soon to know for sure,” explains Lowcock.

He says that fixed income assets are likely to suffer in an inflationary environment so bonds and cash look particularly unattractive. Equities are mixed, with growth stocks tending to be more at risk, whereas there is less of an impact on value stocks:

“Real assets, which can often raise prices in line with inflation, are an attractive route for investors as they offer diversification from equities and bonds as well as inflation protection,” suggests Lowcock.

He recommends Liontrust MA Diversified Real Assets, which invests in a broad range of real assets and infrastructure, either directly or through specialist investment trusts, to give a diversified exposure to the asset class.

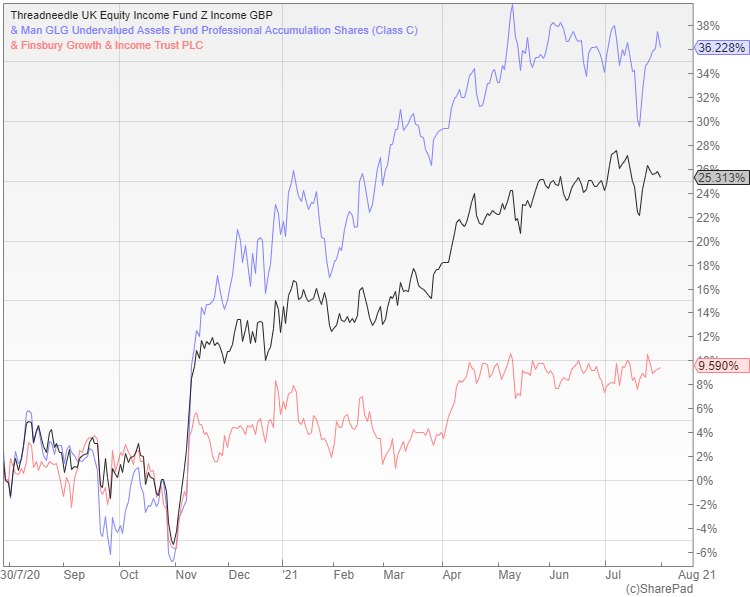

He also thinks that equity income could be a beneficiary, with a decent core option being Threadneedle UK Equity Income

The increase is only transitory

Ben Yearsley, a director at Shore Financial Planning, says that the inflation increases will be temporary, although inflation will go higher than many think, in the short term:

“I don’t see high inflation coming through that stays for more than a brief period. You might see a four to five percent figure at some point this year, but mainly due to the low base effects from last year.”

Rob Morgan, an investment analyst at Charles Stanley, agrees and points out that the shortages that have caused prices of some items to rise should iron themselves out in most cases as supply and demand come back into balance:

“There are also the longer-term structural trends working against inflation such as technological advancements that are making things cheaper and shrinking populations reducing overall demand. Because of this much of the anticipated spike in inflation should prove temporary and the market will continue to look past short-term overshoots in the inflation numbers.”

The key factor to watch is employment and wages. If there are signs of a tight market with staff shortages and widespread rising wages, then this could result in more embedded inflation.

In this sort of scenario central banks would be forced into acting sooner rather than later and markets could take fright. The problem is that it is difficult to call at the moment because of the distorting effects of furlough and support, which are making it hard to unpick the underlying structural trends.

Taking advantage of the uptick

Yearsley points out that even two percentsustained inflation would be bad for bonds as you don’t need high inflation when interest rates and yields are this low. Because of this he says that bonds would be his big underweight exposure, while he would have an overweight exposure to real assets and quality growth stocks:

“Nick Train will do fine, as long as rates don’t go up too much. His quality growth stocks should do well, so I would recommend that you buy the Finsbury Growth & Income Trust (LON: FGT).

FGT holds a concentrated portfolio of 25 stocks, with the 10 largest positions, that include Diageo, RELX, London Stock Exchange and Unilever, accounting for 80% of the assets. It is heavily weighted towards consumer staples, financials and consumer discretionary stocks and has a good long-term record, although the recent lag means that the shares are available at a small discount to NAV.

Yearsley says that this year may be slightly different as a huge number of companies will have pricing power, given that consumers are largely flush with cash, due to not being able to spend much over the last 18 months. Because of this he thinks that a recovery-style fund will do just as well and suggests that Man GLG Undervalued Assets would be a decent choice.

The undervalued assets fund is more about the reopening trade rather than the inflation trade, but it should still prosper under a sustained level of inflation. Manager Henry Dixon has put together a more diversified portfolio than Nick Train and the holdings are very different, with the largest allocations in names such as Royal Dutch Shell, BP, Anglo American, British American Tobacco and Redrow.

Balancing a growth-oriented portfolio

Morgan warns that there are good arguments on both sides of the inflation debate, so investors should have a balanced portfolio that insulates them as far as possible from the impact of different economic scenarios:

“The shift in expectations towards a slightly more inflationary environment might mean there are some decent opportunities in quality growth companies that have underperformed recently. However, it still makes sense to have some assets that stand to benefit from inflation, such as value stocks with the pricing power to pass on any cost increases.”

The vast majority of investors are positioned for a continuation of the low inflation/interest- rate environment where growth and quality continue to outperform. Anyone in this position would be well advised to consider rebalancing in case we see a change:

“What you need are short-duration assets where the cash flow is front-end loaded rather than much further away and where those cash flows can increase at around the level of inflation owing to pricing power,” explains Morgan: “Not many shares fit these criteria, but value or certain equity income funds would be the places to look.”

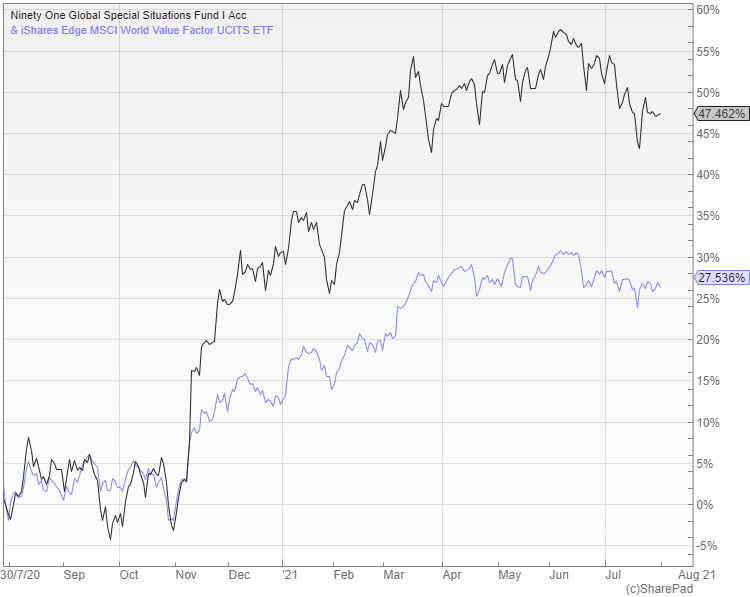

He says that if you are invested solely in conventional tracker funds you have both value and growth stocks already, but a passive option to offset a predominantly growth-style portfolio would be the iShares Edge MSCI World Value Factor UCITS ETF.

This is an unusual fund that attempts to provide exposure to a subset of MSCI World stocks that are undervalued relative to their fundamentals. Interestingly, the main country weightings are the US (41%), Japan (24%) and the UK (10%).

Morgan also highlights the Ninety One Global Special Situations fund for a more aggressive value tilt. It is a high-conviction, concentrated portfolio of global equities that represent the best contrarian ideas of the managers, so it is perhaps best used as a satellite position in a portfolio.

What role should a gold fund play?

The obvious way to profit from higher inflation is to invest in real assets such as commodities, with gold being the primary example. It is generally thought of as the ultimate inflation hedge, although the data isn’t as clear cut as you might imagine:

“It makes sense to have a bit invested in gold, but you must keep in mind that you have to play the long game to make it work,” explains Morgan: “Gold and gold equities have a lot of short-term cycles and significant volatility. However gold should retain its spending power over time whereas a fiat currency will not.”

Holding between five and 10 percent of your portfolio in a physical gold ETF or a fund of gold equities to hedge the risk of particularly high inflation seems sensible, although you would expect in most circumstances for it to underperform the rest of your investments. My colleague Simon Cawkwell has been advocating Golden Prospect Precious Metals (LON: GPM), an investment trust that invests in gold and silver miners.

Yearsley says that he would include a commodities fund, but probably a slightly wider one such as the new TB Amati Strategic Metals that looks at more than just gold. If we are moving to an electrified world, many metals and commodities would be in high demand and this fund would be well-placed to benefit.

At £25m it is very small and is only just getting going after the launch in March. It provides an interesting option with exposure to gold, silver and industrial commodities, as well as speciality metals such as lithium, graphite and rare earths.

Not everyone concurs, with Doran saying that gold is not an inflation hedge and pointing to the 10-year rolling annualised real returns that are often negative, to prove his point:

“Gold worked as a hedge during the Nixon shock, but that was at a time when central governments were seeking to rebuild their gold reserves as the assumptions behind Bretton Woods fell apart.”

The key question facing investors at the moment is whether we will see the return of inflation and although opinion is divided it makes sense to protect yourself against this scenario. Real assets such as commodities and REITs seem like a sensible option, as would a fund that invests in companies that have pricing power, as long as the inflation doesn’t get high enough to really spook the markets.

“the large pool of involuntary savings amassed as a result of the lockdown − over £200bn by UK households and around £100bn by UK companies”

In a higher interest environment this will result in increased income for £300bn of savings.