Where now for oil and the fracking revolution?

One year ago I reported for this magazine that the global oil and gas industry was experiencing one of the severest downturns in 30 years. A perfect storm of overproduction, geopolitical tensions and the long-term move towards alternative energy sources (renewables) had caused oil prices to fall to levels that were often below the long-term break-even cost of production. As I explained, this had impelled the oil majors to diversify into renewables.

The long-awaited rebound in the oil price has now materialised along with synchronised global economic growth. From the low point of below $30 per barrel seen in January 2016, oil reached $70 in mid-January 2018 and is trading as I write at around the $65 mark. Some analysts foresee an oil price of above $70 by the end of the year. As a result, many exploration projects that were on hold are now back on track.

This month I want to look at key new developments in the oil sector, including oil exploration and the service providers that they contract. New technologies in the oil exploration sector could reduce drilling costs exponentially. Meanwhile, the efficacy of hydraulic fracturing – fracking – which last year looked like the future of the oil and gas sector is increasingly coming into question – with potentially dramatic results.

Oil output and demand are set to rise during 2018

According to the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA) the US is poised to become the world’s largest oil producer in 2019, with rising output from shale fields offsetting robust demand growth and supply cuts by conventional oil producers. US crude output, which is up 1.3 million barrels a day compared to last year, will soon pass Saudi Arabia’s output and could even overtake Russia’s by the end of this year[i].

The oil price crash forced US oil producers to cut costs dramatically and to become more efficient. As oil prices have rebounded, they are drilling more wells and production is rising again. The IEA reckons that the growth in US output this year could equal the growth in global demand. It has raised its forecast for 2018 global oil demand growth to 1.4 million barrels per day, given a stronger global economy. It expects total consumption to reach 99.2 million barrels per day this year. Production from outside the OPEC cartel is likely to rise to 59.9 million barrels per day.

The first wave of the US shale boom was propelled by higher prices which spurred global producers from OPEC and Russia to battle for market share through over-production. The shift in policy came in 2017 as lower oil prices impacted the economies of producer nations. They joined forces collectively to reduce output by 1.8 million barrels per day, forcing consumer countries to draw down on global stockpiles. In fact OECD oil stockpiles fell by 55.6 million barrels in December 2017 – the steepest drop since February 2011.

OPEC’s crude oil production in January this year held up at around 32 million barrels per day, though disruption of production in one of OPEC’s largest producers, Venezuela, remains a cause for concern.

The cuts in production initially propelled international Brent crude to above $70 a barrel, although the oil price has retreated further due to the stock market turmoil during the week of 05 February and higher estimates for US crude production. For OPEC and its main collaborator, Russia, revenue maximisation is now the name of the game rather than output maximisation.

The impact of automotive electrification

Oil companies have finally grasped the implications of the rise of electric cars. They are planning for a day when there will be few, if any, petrol stations in city centres – even if they are converted into charging stations. Motorists with off-street parking will generally charge their electric vehicles at home while others will use communal charge points provided by their employers at their place of work.

The number of petrol stations is already declining as cars become more fuel efficient. In the UK, the number of stations has fallen by 80 per cent since 1970, even though consumption of petrol and diesel has risen massively.

Oil companies have finally grasped the implications of the rise of electric cars.

Privately owned Chargepoint has raised investments from Mercedes-Benz owner Daimler AG (ETR:DAI) and German industrial group Siemens AG (ETR:SIE) and is in the process of building a network of electric vehicle charging points across Europe. Oil majors that own petrol stations, such as Royal Dutch Shell (LON:RDS) and BP (LON:BP), have committed to installing electric vehicle charging points at their existing petrol stations. Shell will launch high-speed charging points at retail sites across 10 European countries this year. Last year the oil giant bought electric charging group NewMotion. In February this year BP invested $5 million in FreeWire Technologies with the objective of offering charging points at strategic locations.

Many players in this space see more potential for retail sites which sell food and drink to consumers while they wait for their vehicles to charge, since charging an electric car takes considerably longer than filling an internal combustion engine car with petrol. Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla Inc. (NASDAQ:TSLA), has proposed the company may open restaurants at its network of superchargers.

Doubts about fracking

The recent surge in US oil output has been largely driven by the impact of hydraulic fracturing – fracking – which has been rolled out on a huge scale in many US states, notably Texas, since about 2012 onwards. Fracking has always been controversial and even demonised by certain environmentalists, though the oil majors have maintained that the risks of poisoning the water table are well understood. Recently, doubts about the efficacy and safety of fracking have been voiced even within the oil industry.

Hydraulic fracturing was first used to release shale gas in Kansas by Standard Oil and Gas Corporation in 1947. But the modern hydraulic fracturing technique, called horizontal slick-water fracturing, was first used only in 1998 on the Barnett shale bed in Texas.

How fracking works

Fracking is a means of recovering natural gas from porous rock deep beneath the Earth’s surface. The porous rock is fractured by means of water, sand and chemicals until such point as the rock releases the natural gas contained within it which is then piped to the surface. The fracking boom in the USA over the last ten years has occurred because most conventional natural gas fields have been exhausted. As natural gas prices have risen so fracking, which is complex and relatively expensive, has become economically viable. Fracking has now been used over one million times in the USA alone. Sixty percent of all new oil and gas wells in the USA are drilled using fracking.

Don’t miss Victor’s next piece in the next edition of Master Investor Magazine – Sign-up HERE for FREE

First, a vertical shaft is drilled several hundred metres into the Earth. A horizontal hole is then bored into the gas-bearing rock. Next, fracking fluid is pumped into the ground using immensely powerful pumps. Typically, the fluid consists of eight million litres of water – enough to satisfy the consumption of a typical American town of 65,000 inhabitants for a day – plus several thousand tonnes of sand and about 2,000 litres of chemicals. This mixture penetrates the layer of porous rock and creates innumerable tiny cracks. The sand prevents the cracks from closing again. The chemicals act to compress the water and to dissolve minerals.

Then, most of the fracking fluid is pumped back out of the shaft to the surface whereupon the natural gas can be recovered. When the gas released is exhausted the drill hole can be sealed. Generally, the fracking fluid is pumped back into deep underground layers beneath the water table and sealed there, supposedly for evermore.

Risks of fracking

The main risk is that the water table contained in underground aquifers can be contaminated by the fracking chemicals. If these chemicals interact with a subterranean water source then such water can become highly toxic. The contamination, if it occurs, is so severe that it cannot even be treated. Although this risk has been recognised from the outset, in the USA numerous water sources have been contaminated due to negligence. Moreover, nobody seems to know how long it takes for fracking fluids to contaminate the water table since this is still a relatively new technology.

Some of the chemicals used in fracking are known to be carcinogenic such as benzole, formic acid, methanol and hydrochloric acid. Some environmentalists are concerned that the oil companies that use fracking have not been transparent about the exact composition of these fracking fluids.

A second risk is the release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Most of the natural gas recovered from fracking is methane, which is twenty-five times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide (CO2). The fracking process requires a very large consumption of energy. Sites are quickly exhausted and therefore a much larger number of drill holes are required than for conventional gas recovery. About three percent of the recovered gas is lost in the extraction process which escapes into the atmosphere.

A third risk is that of seismicity – that is causing earthquakes. Environmental campaigners blamed seismic activity in Lancashire on fracking. In 2011, two earth tremors were detected following Cuadrilla Resources’ hydraulic fracturing operations at Preese Hall Farm. The first took place on 01 April 2011 and measured 2.3 on the Richter scale. To determine whether this was due to hydraulic fracturing, Cuadrilla worked with Keele University and the British Geological Survey (BGS) to monitor ground movements around the active well sites.

A second tremor was recorded during the fourth fracture operation at Preese Hall measuring Richter 1.5 on 27 May 2011. Following this and after discussions with the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC), Cuadrilla “voluntarily” halted hydraulic fracturing operations while a report was cmmissioned to discover if there was a link between seismicity and fracturing. The UK Government then imposed a moratorium on fracking.

But a report published in April 2012 by DECC concluded that it was safe to resume hydraulic fracturing, subject to appropriate safeguards and stringent monitoring. Cuadrilla subsequently issued a statement citing “an unusual combination of geological factors” which would be unlikely to recur.

Doubts about the efficacy and safety of fracking have been voiced even within the oil industry.

To put this into perspective, in geological terms, such events are classed as micro-earthquakes and are happening all the time, even in the UK. Most do not cause any material damage. By comparison a “naturally occurring” earthquake in Lincolnshire in 2008 was more than 22,000 times more powerful than the tremor which hit Blackpool on 01 April 2011.

Conventional oil and gas drilling has also been blamed for induced seismicity. According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) only a very small fraction of roughly 40,000 waste fluid disposal wells for oil and gas operations have induced earthquakes large enough to be of concern.

Fracking has proven, over the short-term at least, an effective way to meet our insatiable demand for low-cost energy. But the long-term consequences of fracking are worrying given the risk to drinking water.

Another worry: where does the sand come from?

In the week of 12 February, analyst Lucy Acton at HSBC Global Research released a research note warning that the extraction rate of sand – the second most-used raw material in the world – is running at unsustainable levels. She writes: “Sand mining presents devastating environmental and social issues such as damage to ecosystems, water scarcity and illegal trade. Additionally, transportation of sand and gravel is a significant part of the supply process, both in terms of costs and environmental impact.”[ii]

Fear of aquifer contamination in America

Imaging technology currently under development can accurately trace the source of aquifer contamination along migration pathways to fresh water aquifers. Both environmentalists and some oil companies engaged in conventional oil and gas production would like to see a permanent ban on fracking. They argue that the public perception in the USA of the advantages of fracking shale is far from reality. Moreover, shale drilling may be more expensive than thought – especially if exponents of fracking have to indemnify victims of aquifer contamination.

Don’t miss Victor’s next piece in the next edition of Master Investor Magazine – Sign-up HERE for FREE

From late 2014, when oil and gas prices began to fall, the industry responded by drilling longer laterals with much bigger fracks. Laterals are now commonly more than 3,000 metres long and fracks have expanded from 1 million pounds of sand to as much as 14 million pounds. Shale is naturally prone to aquifer contamination because of numerous undetected near vertical faults that can become conduits when fracked. Some analysts believe that contamination in the Eagle Ford shale field (Texas) is already occurring on a large scale.

If widespread aquifer contamination could be definitively demonstrated by research agencies and by the academic community, that could put the share prices of oil companies which are heavily reliant on fracking under downward pressure.

Three US shale oil producers under pressure

In last year’s article I identified three US shale oil and gas producers which were then riding high. These were considered bellwethers for the sector. How did they do? Let’s just say the US shale revolution has not created shareholder value for some of its leading advocates…

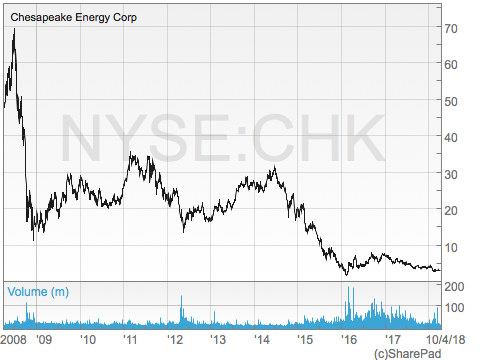

Chesapeake Energy (NYSE:CHK) operates in Louisiana, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wyoming. In February last year Chesapeake announced that average 2016 production amounted to 635,400 barrels per day – in line with 2015 levels. Total oil and natural gas proven reserves stood at 1.7 billion barrels of oil equivalent, a 14 percent increase compared to 2015. The company had succeeded in reducing production expenses by about 28 percent as compared with 2015. What happened to their share price? Between February 21 2017 and February 16 2018 the share price declined fairly steadily from $6.08 to $2.73! So the share price more than halved essentially because it has still not fulfilled its objective of breaking even this year.

2016 was a “transformational year” for Oklahoma based Devon Energy (NYSE:DVN) according to its CEO. The company decided to focus on its top two franchise assets, the STACK field (located in the Anadarko Basin of Oklahoma) and Delaware Basin field. The company’s drilling programmes generated the best well productivity in its 45-year history. At the time of writing one year ago DVN’s share price was trading at $45 – as I write in the third week of February 2018 it is at around $34.

Whiting Petroleum (NYSE:WLL) is a crude oil producer in North Dakota where output is 130,000 barrels of oil per day. It also operates substantial assets in northern Colorado. Headquartered in Denver, Colorado, Whiting’s share price rose by over 160 percent from February 2016 to February 2017 when it reached $46. In late February 2018 it is trading at about $23. Once again – a share which has halved in value.

The UK: the fracking boom that didn’t happen?

Here in the UK we are sitting on a huge subterranean belt of shale. This is rock which was laid down in the Palaeozoic Era some 250-500 million years ago. In September 2011, a leading player in UK shale gas, Cuadrilla Resources, announced that it estimated that there could be 200 trillion cubic feet of gas under the Bowland shale bed in Lancashire alone.

During the week of 05 February a hitherto secret government report was revealed to the UK media after Greenpeace uncovered it via a Freedom of Information request. The 2016 report suggested that the promise of a shale gas fracking bonanza in the UK has been greatly exaggerated. The Sunday Telegraph reported[iii] that “the Government has known for almost two years that the number of wells likely to flow [sic] shale gas from fractures deep beneath the Earth will be just a fraction of the 4,000 wells quoted publicly by ministers…”

In fact the total number of viable shale wells in the UK is likely to be in the order of 155 as compared with the 400 per year envisaged in a previous report from Ernst & Young (EY). This report fuelled claims that a shale revolution could drive £33 billion of new investment and create over 64,000 jobs.

This will be music to the ears of environmentalists but represents a blow to tacit government policy. In Chancellor George Osborne’s Autumn Statement on 05 December 2012, almost unnoticed by the media, he set up a new body called the Office for Unconventional Gas and Oil. And in the small print to the Statement, the Chancellor outlined tax breaks for fracking companies – even though at that time fracking was technically still outlawed in the UK. A week later, on 13 December 2012, the moratorium on fracking in England (though not in Scotland) was removed by statutory order.

The UK was a significant offshore gas producer for many years but production peaked in 2000 and has since been in rapid decline. The country has gone from being a net gas exporter in 2003 to being dependent on imports of gas today. By 2020 the UK may only be able to meet about one quarter of its natural gas demand from domestic production.

The shortfall has been made up by imports of piped gas mainly from Norway, the Netherlands and Russia, supplemented by imports of Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) by ship from Qatar, the latter amounting to about 40 percent of total consumption. The appeal of domestically produced shale gas is that it would reduce Britain’s dependence on potentially vulnerable overseas suppliers – and thus improve our energy security. Opponents of fracking argue that the debate has moved on as the price of renewable energy continues to fall. Even energy executives consider that it would be difficult to replicate the US shale gas boom in the UK given the difficulties of drilling in a much more densely populated country.

Halliburton (NYSE:HAL) – the canary in the coal mine?

Halliburton’s shares wobbled on 15 February after the giant American oilfield services group revealed that it expects to take a hit on its next quarterly earnings because of delays in sand deliveries to oil firms active in fracking. These delivery backlogs are expected to cost 10 cents to its EPS in Q1 2018. Halliburton is a major provider of inputs and services to the US shale industry including the pumps and fluids used in fracking. At time of writing the shares are trading at $47.50 yielding a top-heavy P/E ratio of 127.

Four fracking companies active in the UK

There are just a small posse of unconventional oil and gas producers which are already generating gas and oil here in the UK.

Cuadrilla Resources is owned by the quoted Australian mining services company AJ Lucas (ASX:AJL) (45%), Riverstone Holdings (45%) and company management (10%). Cuadrilla announced on 12 January that it was “very encouraged” by the results obtained from a pilot well stretching 2.7 kilometres into the ground at its site near Blackpool. Completion of the well signals a resumption of hydraulic fracturing for the first time since fracking was halted in 2011 after supposedly causing earth tremors. Cuadrilla’s latest drill site at Preston New Road was allowed to proceed in 2016 after Sajid Javid, Communities Secretary, overturned a decision by Lancashire county council to block the plans. However, Cuadrilla will require final approval from the new Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Greg Clark, before it can resume fracking.

Third Energy, another shale gas company, is awaiting consent from Mr Clark to start fracking a vertical well at Kirby Misperton in North Yorkshire.

Even energy executives consider that it would be difficult to replicate the US shale gas boom in the UK given the difficulties of drilling in a much more densely populated country.

IGas Energy PLC (LON:IGAS) bought out the UK operations of Dart Energy Ltd. (headquartered in Singapore but managed from Brisbane, Australia) in May 2014. Dart Energy emerged from the de-merger of Arrow International’s unconventional oil and gas assets in 2010. It was said to command specialist expertise in the field of unconventional gas exploration and with a portfolio of 52 licensed sites across eight countries. IGas’s share price has fallen from over 200 pence in February last year to 77 pence at time of writing.

In March 2017 Swiss-based Ineos increased its exposure to UK shale gas by acquiring a portfolio of onshore exploration and production licences from Engie SA (EPA:ENGI), the French energy group, in an effort to bring US-style fracking to Britain. For Engie the withdrawal was part of its strategic re-positioning away from production to consumer-facing businesses. Ineos Group, privately controlled by its founder and chairman Jim Ratcliffe, is already the biggest owner of shale licences in the UK and last year’s deal increased its land holdings by 10 percent to more than 1.2 million acres.

Advances in oil exploration technology

Conventionally, oil exploration companies start with detailed geological surveys, satellite photography, airborne reconnaissance and seismic samples and begin to drill in promising locations. Unfortunately, most wells drilled are wildcat wells which disappoint. Often the confirmation of the existence of an economically viable oil field requires numerous drilling operations. This is an expensive and time-consuming process – even more so when conducted offshore. Any technology that would permit oil explorers to strike oil first time would reduce costs dramatically.

On a recent trip to the USA I was privately briefed about an embryonic Texas-based start-up which has developed a proprietary technology which could revolutionise oil exploration. The technology in question uses sensitive instruments to monitor natural radiation being emitted from the Earth’s core. It detects changes in the frequency of naturally occurring gamma radiation to pin-point the location of hydrocarbon deposits deep below the surface. As the Earth’s natural gamma radiation passes through hydrocarbon bearing rock structures it minutely but detectably changes frequency. The changes of frequency can also indicate the extent of the oil and gas reserves.

Don’t miss Victor’s next piece in the next edition of Master Investor Magazine – Sign-up HERE for FREE

In principle such technology would permit operators not only to find high concentrations of commercial oil deposits, but also potentially to find precious metals (silver, rare earth minerals) and accurately map these deposits within their fracture systems. Reliable mapping of such deposits would allow for efficient extraction methods which would be more environmentally responsible.

It could also be used also to find faults that can become conduits for oil and gas migration. Visualizing the movement of oil and gas from source rock to reservoir rock would give oil explorers an extraordinary level of detail previously unavailable. One oil major that is rumoured to be investigating the use of this revolutionary new technology is Saudi Aramco – which is likely to be listed on either the New York or London markets later this year.

Outlook

The medium to long-term outlook has not changed over the last year. World GDP will nearly double between now and 2035 driven by fast-growing emerging economies where more than two billion people will be lifted out of poverty. Yet efficiency gains and electrification will greatly reduce oil consumption per person. While global GDP will increase by over 90 percent between now and 2035, energy demand will increase by only around 30 percent.

The share of hydrocarbons in the fuel mix will continue to decline, although oil and gas, together with coal, will remain the dominant sources of energy. Renewables, along with nuclear and hydroelectric power, will provide half of the additional energy required out to 2035.

Action

My recommendation last year that investors’ exposure to the oil sector should be biased towards those oil majors which are diversifying into renewables still stands. I cited Total SA (EPA:FP) as a benchmark. I am no longer so bullish, however, on those oil majors which have very large investments in the shale oil and gas sector such as Statoil (SWX:STL) and the second-tier US oil majors such as the three discussed above. If an incoming Democratic President were to arrive in the White House in January 2021 with a mandate to ban fracking – which is quite conceivable – the cat really would be set amongst the pigeons…

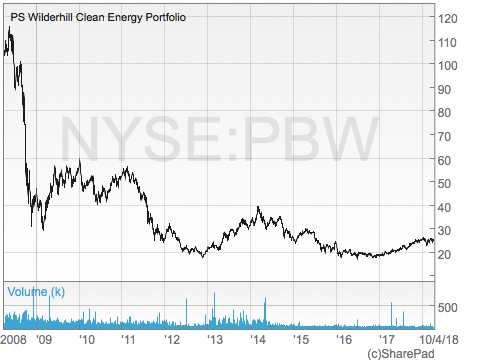

I’ll be having much more to say about investment in renewables this year. Meanwhile, check out the Power Shares Wilder Hill Clean Energy ETF (NYSEARCA:PBW). It’s going places.

[i] See The Financial Times 13 February 2018, available at: https://www.ft.com/content/1904fd3c-109a-11e8-8cb6-b9ccc4c4dbbb

[ii] Reported in the Financial Times, 15 February 2018. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/372fe44e-1265-11e8-940e-08320fc2a277

[iii] Ministers exaggerated fracking boom, Sunday, 11 February 2018, page B1.

If you auntie had a moustache, then she would be your uncle and the cat could well eat the canary. On the other hand…