It Still Pays to Invest in Europe

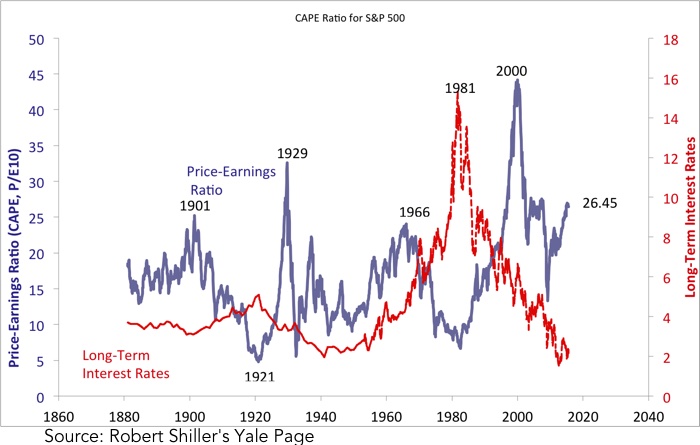

At a time when the S&P 500 is celebrating a six-year rally, which has seen it clock up gains of more than 180% since its 2009 low, it is understandable that investors should start to ask when this bull run will run out of steam. While economic improvement has been substantial since the financial crisis, there are still a few drawbacks that may play against this market. One is obviously growth, which has not been as strong as one would expect during a recovery phase; and the other is the end of monetary easing. When mixing rapid price appreciation with parsimonious economic growth, we usually end with a disconnect between share prices and real value. If we look at the Cyclically-Adjusted Price-Earnings (CAPE) ratio for the S&P 500, that is exactly what we find. The ratio currently shows a reading of 26.5x, which is 60% above its historical average of 16.5x. If more than 100 years of history are worth something, then it is time for investors to look for value elsewhere because there is none in the U.S. stock market.

In the long run, the only strategy that pays is to buy under-valued stocks and sell over-valued ones. Investors should not pay too much for the expected profits of a company. A good way of finding value is too look at price-earnings ratios and check how much an investor is paying for future earnings. But these ratios suffer from cyclical variations and are frequently negative during recessions, making it difficult to interpret. At the same time, expected future earnings are not realised values but just estimates. Theory shows that earnings estimates are systematically biased upwards, which make the ratios appear better than they really are. Just look at the expectations that are usually attributed to companies that have never seen a profit… In general, the price-earnings ratio fails to give guidance to investors.

The alternative that was developed by the Nobel-Prize winner Robert Shiller is to use the CAPE ratio, which takes into account the average earnings of the last ten years adjusted for inflation. While measuring the past ability of a market to make profits, it has been shown that any departures from that average are short-lived and don’t really reflect any increased ability to make higher profits. Over the long-run, above-average corporate profits in strong years cancel out below-average corporate profits in weak years. There is a mean reversion. A strategy of purchasing stocks when the ratio is below average and selling them when it is above average delivers long-term profits. Even during life-changing events like the generalisation of mass production, the end of the gold standard, or the tech revolution, when equities rose to unprecedented CAPE ratios, the effect was later reversed. There is no evidence that “this time is different” and the CAPE has been a strong predictor of equity returns.

As corporate profits have been growing slowly in the U.S., the Federal Reserve’s massive asset purchase programme has been contributing to the increase in the CAPE’s numerator. As a consequence, this ratio rose more than 60% since February 2009 when it was around 15x for the S&P 500. At that time, and according to the historical average of 16.5x, stocks were already reasonably priced, which suggests that the crash was a necessary adjustment. But the massive asset purchases from the Federal Reserve led to a new departure from intrinsic value.

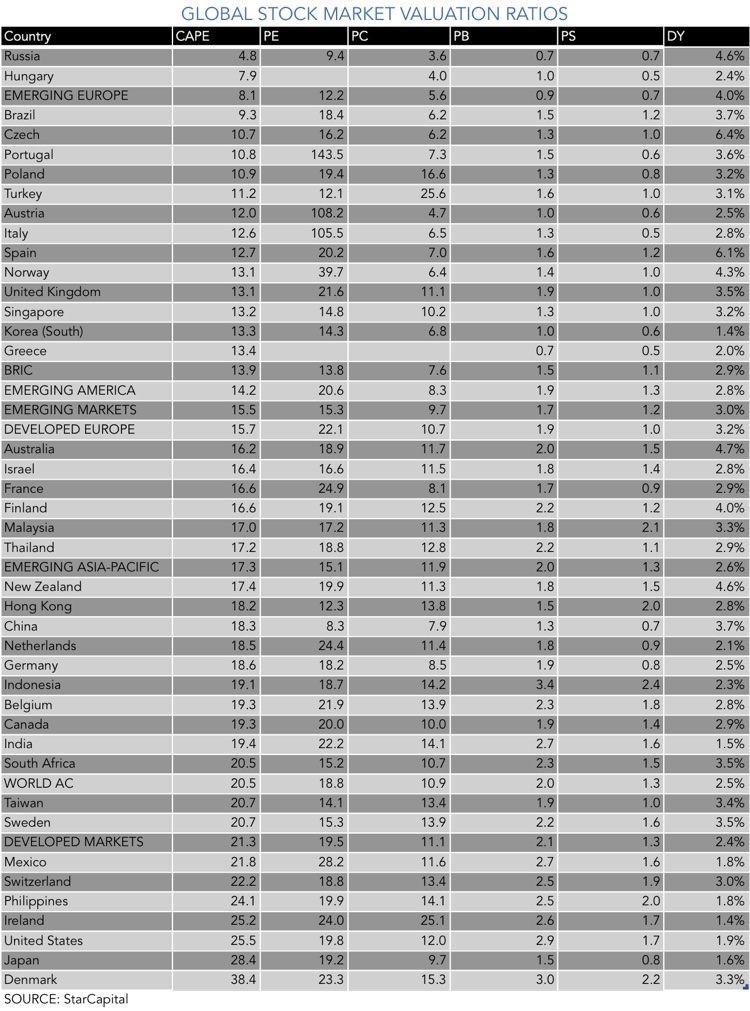

At a time when profit growth in the US is expected to be c. 1.6%, the prospects for any outperformance of the S&P 500 are eroding quickly. But not all is lost for equity investors, as Europe is expected to see a 9% increase in corporate profits. The European economy is behind the US economy and it is still at the early stages of a recovery. Inflation is low but still above what is considered potential problem territory (deflation) and the unemployment rate is near a three-year low. Valuations look attractive. Even for countries like Germany and France, which have benefited the most from European QE, the CAPE ratio is still at 18.6x and 16.6x respectively, which is much below that of the S&P 500. In the UK, for example, where QE has been in place for some time, the market doesn’t look overvalued, as the CAPE ratio is at a modest 13.1x, still leaving upside potential.

But when speaking of value, one cannot ignore those markets that were severely hit by the sovereign debt crisis. Portugal, Italy and Spain still have the most depressed valuations, ranging from 10.8x to 12.7x. Greece also shows a low CAPE ratio, but the current instability makes it too risky, at least until the deal with the EU is agreed and comprehensive details are published. Ireland is looking overvalued.

Going deeper into our search for value, we can find some of the best opportunities arising from Emerging Europe in markets like Hungary, the Czech Republic or even Russia. In the case of Russia, the CAPE ratio is at an excessively depressed 4.8x. Of course there is an issue with oil prices and an on-going deep recession, but it is exactly when CAPE ratios and sentiment levels are at their lowest that the best long-term investment opportunities arise. By the same token, the whole mining and oil industry is surely a buy at this point…

At a time when the U.S. market seems overvalued and the Federal Reserve is positioning itself for the first rate hike, it is time to quietly reduce the exposure to that market and look for value in Europe, where the best opportunities lie.

Comments (0)