Which theory supports central banks?

The equivalent to cheap money is expensive “everything else”. When money is made abundant while the stock of assets is held constant, inflation must pick up. But the higher prices do not always come in the form central banks wish for…

There are so many things money can buy. A watch, a pack of beer, a meal at a restaurant, a haircut, a house, a share of a company’s stock, a flight ticket to the Bahamas, and even a rare 1960s Ford Mustang. Part of these transactions are related to GDP and their price is captured by CPI measures; other parts are non-GDP transactions which are not captured by the same measures. In either case, a rise in prices represents a loss of purchasing power, but only in the first case is such a loss accounted for by the official inflation measure.

Then, if a central bank pumps money into the economy and that money flows disproportionately to non-GDP assets, we may end with very low inflation, as measured by CPI.

While I’m not willing to develop a global theory about how money flows, there are a few ideas that come to my mind. For example, in a developed economy, where the population has on average more than satisfied its basic needs, the marginal utility of consumption is lower and it may very well happen that, faced with more money than needed, the population just spends this extra liquidity on non-GDP items. Instead of spending the extra dollars at the butcher, people may instead purchase houses, old collectibles, beautiful paintings and income-producing assets. A natural consequence would be for consumer prices to remain unchanged while the price of “everything else” would increase. If that is what really occurs, then, a central bank purchasing assets on a large scale while keeping key rates near zero during a prolonged period of time could be generating asset bubbles without doing much for consumer inflation. I would say that, under such circumstances, and for the sake of achieving its inflation goal, the central bank would be better off by directly purchasing consumer goods. Policymakers could even pay themselves in good meals and expensive haircuts, and purchase the items that are part of the CPI index tracked by the central bank. If carried out on a sufficiently large scale this would definitely generate consumer inflation. If inflation is the only target, this is the best way to achieve it. No need to distort the bond market and other financial markets. At the same time, and unlike what would happen if the government did the same by itself, there’s no debt arising from it, as the central bank can always print more money.

What the theory says…

One of the most important duties a central bank has is to serve as lender of last resort, in order to avoid panics. When banks can no longer attain financing from other banks they can always get it from the central bank. This was the main reason why the FED was created.

To honour their duty as lenders of last resort, central banks should provide liquidity to the market when there is a shortage of it, as they did during the 2007-2009 financial crisis. But central banks have been doing much more than that; they have massively expanded their balance sheets, flooding the market with excess liquidity, in the hope the market picks it up and lends to the real economy such that inflation gathers proper pace.

Milton Friedman once attributed the rise in inflation to a rate of expansion of the money stock in excess of increases in the amount of money demanded in the economy. For Friedman, the demand for money is relatively stable and monetary imbalances are the result of an inadequate money stock growth, which is controlled by the central bank. “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”, such that the central bank should be protected from government interference and adopt a rules-based monetary policy. The central bank should only provide the necessary liquidity, as determined by the demand for money. Any attempt at providing more than that would just lead to inflation with no permanent gains in employment. Friedman was behind much of what was done during the 1980s and 1990s, which put an end to decades of inflation. But controlling inflation proved insufficient to drive the economy to full employment. With Friedman in mind, and with the additional notion that deflation hurts production and demand, central banks started looking at Friedman’s view in reverse order. If inflation is low, the central bank can then flood the market with more liquidity than needed such that inflation should pick up. And when it doesn’t, the central bank can just increase the pace of the money expansion, flooding the market with ever more money. But they forgot that inflation might manifest itself elsewhere.

The Austrian theorists take a different view. They believe that all central banks really do is kick the can down the road to create even bigger problems than the one they are trying to solve. The interest rate should represent the time preference and be the basis for the allocation of inter-temporal consumption decisions. At the same time, it is also the basis for the decision between consumption goods and capital goods. By artificially lowering the interest rate, a central bank is giving wrong signals to the economy. More capital goods and less consumption goods are produced than should naturally result; and instead of the economy getting rid of the accumulated waste, it is just creating new imbalances. By this token it is easily seen that for the Austrian School of thought the best cure is to allow the market to function and avoid messing with the interest rate. The more liquidity a central bank pumps into the market, the worst the future will be.

Then we have Keynesians and all the new DGSE models that try to bring new life into the old Keynesian models. These models are often used by central banks. But, if Keynes is of use here, then monetary policy would not be the best route to improve the economy. Unemployment and GDP growth are best tackled by the government and fiscal policy rather than monetary policy, as private investment will not rise sufficiently with an interest rate decline, in a depressed economy. When interest rates are near zero, monetary policy would be completely ineffective.

…The central banks ignore!

While the advised action differs widely among all the above models, there is one point in common among them: none can give support to the current central bank action. With time, central banks gained life and expanded their range of interventions, without any care with the collateral damage they could inflict on the economy. The central bank is no longer a lender of last resort or a guardian of price stability; it is an inflation-centric entity that is willing to pursue a nominal target no matter what happens. But what if the central bank is creating epic bubbles? What if the price dynamics the central bank so vigorously pursues were not captured by the CPI measures it follows?

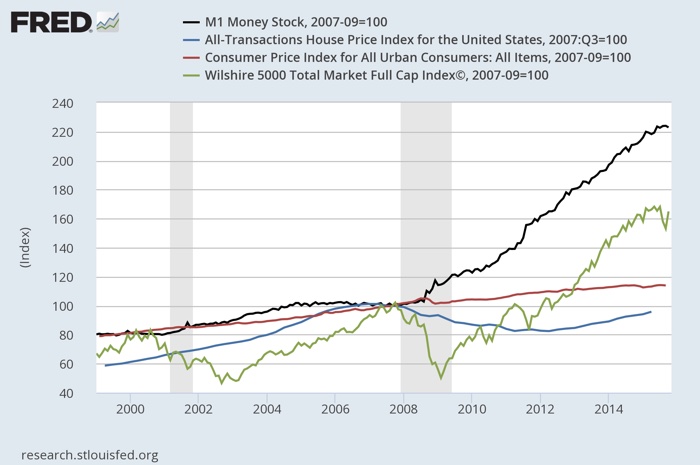

Since the first rate cut occurring in September 2007, the FED has allowed M1 to expand by 123%. With GDP expanding very mildly, one would suspect that consumer prices were tremendously high, but they aren’t. During the 8-year period CPI is up just 14%. Where is the money going?

The money is going to the financial economy. The equity market, represented in the picture by the Wilshire 5000 index, is up 65%. Other assets, which are not part of CPI, saw similar price increases during the period. The central bank has been very effective in generating inflation; it just doesn’t measure it accurately. No matter where the price increase comes from, it always reduces the purchasing power of money. During a period of time, the wealth of those who own financial assets will improve due to the higher prices, but as the income-generating capacity of those same assets will remain unchanged, the increase is not sustainable, and will sooner or later revert. What the central bank is doing is creating asset bubbles. In trying too hard the central bank became part of the problem.

Comments (0)