Sweden is Heading Towards Disaster

Following the Leader

It is always entertaining to listen to European officials speaking in a placid tone as if everything were under control. Greece is on the brink of leaving the Euro; austerity policies have wrecked a few peripheral economies; debt levels are higher than before the financial crisis; and output growth is languishing. But there are still reasons to believe they’re following the path that leads to success. As European governments capped themselves in terms of fiscal intervention to save Europe, everyone is waiting for Mario Draghi to play his tricks and reignite growth… and he is doing exactly that. Draghi is attacking deflation with all the tools available, as he perceives it as the worst enemy, one that prevents growth from happening. Just imagine how worrying it is for all of us to pay less for the same products we buy every month! They say this leads to a downward spiral in prices, creating a mechanism that is self-fulfilling. But the British very well know how untrue that is, as they tend to increase their purchases as soon as they see a price drop. So, it is reasonable to ask how meritorious it is to tackle inflation with financial weapons of mass destruction. Is it really true a consumer will delay purchases when prices are declining? If that were the case, then the whole computer industry would have stalled long ago and I would be writing this article on a sheet of paper with the help of a pencil, waiting for laptop prices to finally stagnate…

Through tackling inflation with negative deposit rates, zero refinancing rates and a pile of debt purchases, Draghi has created a radioactive cloud that is flying over Switzerland, Denmark and Sweden. Unlike in the UK, where monetary policy still has a good degree of autonomy, the Swedish, for example, are completely bound by the ECB’s actions and have no other option than to follow it, even if it leads the country towards disaster. The pursuit of an inflation target by central bankers has become so imperative that they are willing to sacrifice everything else in search of it.

Creating Real Estate Bubbles

The Swedish Riksbank is on a collision course with its economy. Following in the footsteps of its neighbour ECB, the Riksbank just cut 10 basis points on its repo rate to a current level of -0.35%, while increasing government bond purchases by SEK 45 billion (£3.42 million). Inflation in Sweden has been subdued during the last few years and below the 2% target, but other more important dynamics are developing behind consumer prices that should have been weighted by the central bank and prevent it from engaging in experimental policies. I’m referring to real estate prices and household debt.

For those who believe there is a bubble forming in UK property prices, the Swedish case will make them think again.

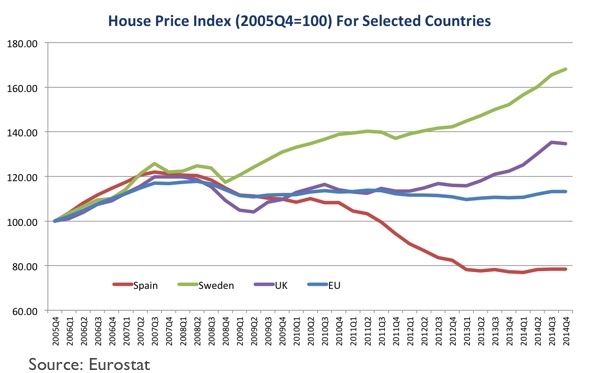

During the last 9 years (between the beginning of 2006 and the end of 2014), house prices rose 13.3% on average in the EU. However, that figure hides some extreme divergences. In Spain, for example, where prices rose during the 1990s and early 2000s, prices declined 21.5% from 2006 to 2014. In the UK, the crisis was felt in 2008 and 2009, but the market soon recovered to post a rise of 34.6% in the period under consideration. But the real extreme here is the case of Sweden. The country was not hit by the crisis and house prices never stopped increasing. From 2006 to 2014, prices rose by 68.1%. The trend is not new, as the Swedish had already experienced a massive boom in property prices during the 1980s and early 1990s, which culminated with a bust in 1992, which wiped out two-thirds of property value. Two commercial banks had to be bailed out. But then prices start rising again and are now approaching new bubble levels.

In 2011 the Riksbank made an attempt to address the housing problem by hiking rates. At that time it was heavily criticised (Paul Krugman was at the top of the critics list, only to later recognise the country was creating a bubble). As I have mentioned in several past blogs, CPI is handicapped as a measure of price increases. It doesn’t take into account many items people purchase and it completely misses any increase in the prices of financial assets and in the prices of assets produced in previous periods. Central bankers think there is a lost link between the increase in the money stock and the increase in prices. If interest rates are decreasing and the money stock is expanding, then either GDP is increasing in proportion or prices are rising. But when I say prices, I’m not restraining myself to the handicapped CPI. I’m considering everything else missed by such a measure.

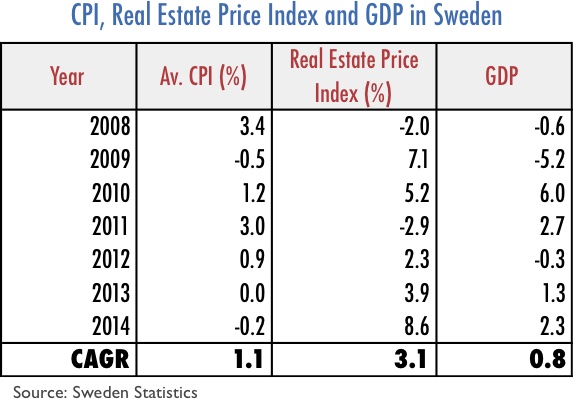

Between 2008 and 2014 consumer prices rose at a compound annual rate of 1.1%, GDP rose at a pace of 0.8%, and real estate prices at a rate of 3.1%. The money stock is finding its way through the system, but instead of leading to decent GDP growth it is going towards raising the prices of financial assets and real estate. The low CPI numbers are not a reliable indicator for central bank action.

Riskbank Threatens To Act

The statement that accompanies the Riskbank decision expresses two main developments that led the bank to cut its repo rate yesterday. On one hand, the bank is worried about the financial consequences of the situation in Greece. On the other, since its April rate decision the Krona has become stronger than anticipated and poses a heavy risk to the inflation goal. These concerns are fair, as Sweden has been seen as some kind of safe haven for scared European investors. If next Sunday Greece says “No” to bailout funds and the crisis intensifies, the Krona looks destined to appreciate even further and the Riksbank may be forced into a surprise cut. In its statement the bank anticipates such a situation as it threatens to do more if necessary “even between the ordinary monetary policy meetings”. They add that “the repo rate can be cut further and the government bond purchases can be extended”. I’m not really sure about either of the two. If the rate could be cut much further the Riksbank would have cut it at least 25 basis points instead of just 10 basis points. We know that zero is not the lower bound for the main central bank rate but we do know there is a lower bound for it. When that limit is surpassed, some pernicious effects may occur. If the situation deteriorates in the Eurozone, Sweden’s 2% inflation target will be in trouble and the country will most likely enter a deflationary period.

The Current System Just Doesn’t Work

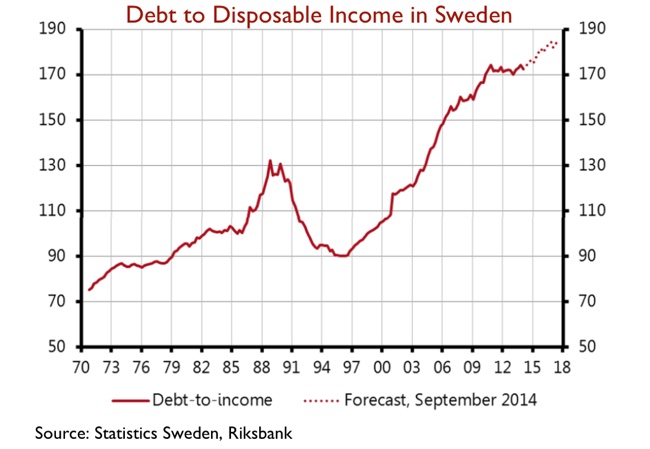

We shouldn’t become too concerned with deflation in consumer prices. What is really worrying is the rise in credit and real estate prices. The current position of Sweden in Europe and the current predicament of the Eurozone will prevent the Riskbank from hiking its repo rate, which would be a necessary step to prevent a crisis similar to the 1992 one. Mortgage rates are currently under 2% and are fuelling very rapid rises in real estate prices. Last year prices rose 8.6%, after rising 3.9% in the previous year and 2.3% in the year before that. In the Greater Stockholm area prices rose 13.1% last year. The question to ask is are such rises sustainable? The following chart may help to reveal the answer.

Debt-to-disposable household income has been on the rise since the 1992 crisis, and is currently above the 170% level. With interest rates being kept so low for so long, there is a clear incentive for households to increase debt. Currently, more than 50% of bank loans go in the direction of real estate. This means that if economic conditions deteriorate just a little, Swedish banks may experience a spike in bad debts and real estate prices will decline rapidly, which will lead to a further deterioration in the financial position of the banks.

In my view, the Swedish case adds evidence to two main issues regarding the current situation facing central banks. First of all, it is time to review their mandates regarding price stability. They should pursue the stability of the purchasing power of money across all assets, not the stability of the prices of a few products and services included in a basket that doesn’t even fit the standard purchases made by a typical consumer. Second, for a small country under a fractional reserve system, it is better to adopt the currency of the bloc with which it trades the most, rather than to keep its own currency. To keep monetary sovereignty and avoid financial crisis at the same time, one just can’t keep a fractional reserve system.

Comments (0)