The risks are piling up in emerging markets

Financial markets have been on an impressive run since Donald Trump was elected in November. The S&P 500 is up 10.7%, the Dow is up 13.1% and the MSCI World (which is a proxy for developed markets) is up 9.9%. Trump’s promises in terms of tax cuts, infrastructure spending, protectionism for US industries, repeal of environmental legislation and deals – among many others – have helped boost investor sentiment, especially in the US. Coupled with positive economic data for growth and employment, the mix played very well for those holding long positions in equities.

But with Trump also came a stronger dollar and interest rate hikes which dented optimism in emerging markets, at first at least. A strong dollar and higher interest rates could quickly derail their finances, as these countries are often leveraged through dollar-denominated debt. A higher dollar and higher US rates would mean tougher credit conditions for them. But things have changed quite a bit since the beginning of the year and the good vibrations shared by US investors have become entrenched pretty much everywhere, with emerging markets being no exception.

In fact, as an asset class, emerging markets is among the top performers for the year. But, in my view, the main reason for this is not fundamentals-related but instead momentum-based, such that the risks are piling up even as money pours into these assets. With emerging markets and their respective currencies having been on a good run so far in the year, I wonder whether this might be a good time to go against the crowd.

Since the peak of the financial crisis (which coincides with the bottom of the market) in March 2009 until now, the S&P 500 has risen 250%, which translates into a fat annual compound rate of return of 12.1%. Just three months into the year, the S&P 500 is already up more than 5.5%. On average the S&P 500 has risen around 7% or 8% at most for the last few decades. Many years of quick monetary expansion, mixed with a positive feedback effect, have been attracting too much funds into the market.

But a 12% annual return is just unsustainable, particularly at a time when long-term real rates of return are seen as being the lowest ever (ask central banks about it!). These returns are unsustainable, which means prices will have to decline (or rise very slowly) in the near future. One could argue that the same reasoning could have been made two years ago, just to see the markets rise for two more years. With the US economy on a good run in terms of growth and employment, there’s no reason to be pessimistic, many would think.

That’s true, but we cannot ignore the risks. While the prospects for the US economy are good, growth is hovering around 2.1%, which is by no means a fantastic pace. The economy is growing, profits are growing, but such growth hardly justifies the spectacular run-up in equity prices. Another risk comes from Trump’s inability to change the status quo, which is contributing to a fall in his popularity.

In a world plagued with low inflation and low growth, Trump’s promises played like music to investors’ and consumers’ ears. Markets reacted accordingly and equities became overvalued in anticipation of Trump’s proposals. This contributed to a decline in expected returns in the US and boosted capital outflows in the direction of emerging markets.

Investors were initially cautious regarding the impact Trump could have on the emerging world. By the time of the US election, equity prices were declining in emerging markets. A second round of setbacks came in December, when the FED hiked its key rate. But by the new year investors had shrugged off the impact of higher interest rates on emerging markets and instead turned optimistic, moving money into emerging-market equities and debt.

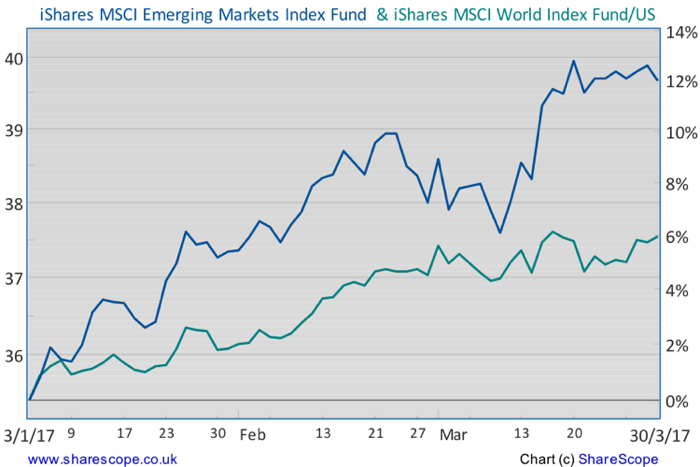

Since the beginning of 2017, the S&P 500 is up 5.5% and the MSCI World is up 6.7%. Emerging markets, here tracked by the MSCI Emerging Markets index, are up an impressive 12.6%. Blackrock, the company that owns the iShares ETFs, recently reported that its iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (NYSEARCA:EEM) has never attracted so much money as it has done recently. A lot of money is also being directed towards dollar-denominated bonds from emerging markets, as investors seek out higher yields than those offered by US Treasuries and corporate America.

Frontier markets, where risks are relatively high, are issuing (or planning to issue) dollar-denominated bonds too. Papua New Guinea is a good example of a particularly poor country that is planning to issue $500m in five-year debt later in the year, for the first time. But, if there’s demand, why not issue the bonds? Who can criticise them?

Global optimism is too high for my taste. I’m looking at the current picture and I’m seeing too many risks. In 2007-08 and 2009-10, we experienced a similar inflow of money into emerging markets. By then, everything ended badly. These money flows are seeking out the highest yield possible rather than being part of any long-lasting capital movements seeking real investment opportunities. There is a risk the Trump trade comes short of expectations. Until now, Trump has done next to nothing in terms of his biggest promises and has been blocked a few times already, either by the courts or the House. Trump’s health bill just fell short of his intentions.

One can then ask: Will Trump be able to proceed with a fiscal shock at a time when the economy is perceived to be close to full employment? Will Trump be able to cut taxes in any significant way? I doubt it, and because of this, I believe the S&P 500’s trajectory may be tapering off, as realism replaces optimism. The US economy isn’t going to grow at a much higher pace, particularly because the FED will continue to tighten policy, albeit slowly. Expected equity returns will rise in the near future as will bond yields. This will reverse the direction of capital flows, in favour of the US.

The long-term outlook for emerging markets isn’t that great. Money inflows have more to do with the low yields in the US and higher commodities prices than anything else. These countries have been issuing too much dollar-denominated debt and may have trouble in the near future when it comes to servicing that debt. I would avoid those countries where the current account is negative and where government deficits are high at the same time.

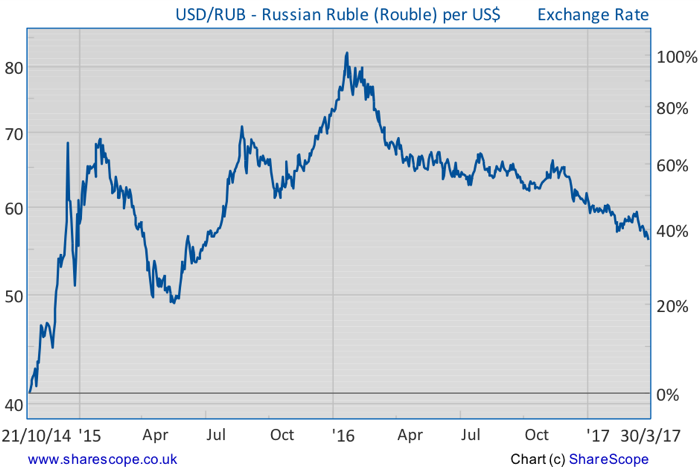

At an individual country level, Mexico is recovering from an overreaction to Trump’s promises and I remain positive on Mexican equities. At the other end of the scale, Russia is a case where investors are piling in to just profit from the carry trade, as interest rates are near 10%. But I wouldn’t trust the rouble right now. With oil prospects being relatively poor and the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) now likely to engage in a wave of rate cuts, the rouble will come under pressure against the dollar. I’m a seller of the rouble and the iShares Emerging Markets ETF (EEM).

Forgive the numbskull question, but where is the money driving up equities coming from? And if US and emerging market company earnings are likely to be poor and cannot justify their elevated share prices, as Mr Costa claims, where should investors be putting their investment cash instead?

We keep being told that bonds are mostly massively over-valued, as are US equities and property generally in developed markets, and that poor/average valuations in Europe, Japan, the UK and so on simply reflects their poorer economic prospects/Brexit uncertainty/specific local conditions, etc. At times, it feels like there’s nowhere suitable for investing, because we’re told everything is either priced fairly or is overvalued due to QE and excessive optimism. So is Mr Costa a buyer *anywhere*?