Japan needs people, not archery!

We are now celebrating the third year of Abenomics in Japan. After being in a dormant state for more than twenty years, the Japanese economy was in need of someone that could revitalise it through shock and awe. Shinzo Abe promised what others didn’t and quickly ascended as Prime Minister to unfold a three arrow plan, which became known as Abenomics. He promised to: (1) conduct a bold monetary policy (similar to what Ben Bernanke was doing in the US); (2) consolidate public finances that were already showing debt of more than 200% of GDP; and (3) engage in structural reforms to spur longer-term growth. But during the last three years Abe has had to tweak his plans several times, as his archery seems to be missing the target. Can he still save Japan from deflation? I think he can’t. Japan’s problem isn’t deflation or lack of growth, but lack of working-age people. Deflation is just the free market adjustment (symptom) to a changing reality (disease).

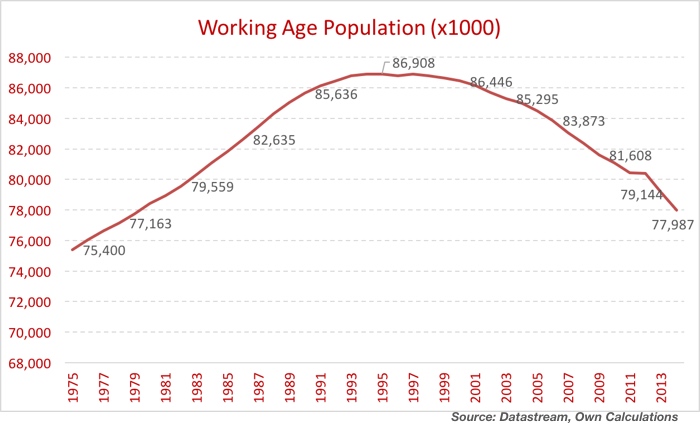

The Japanese economy is not weak, nor is it lagging behind other developed nations, like Europe and the US. On the contrary, Japan lives at least 20 years ahead of everybody else and is now experiencing what others will in the future: an ageing population, low birth rates, and increasing life expectancy, which must culminate in lower wealth and price deflation. Every year, the population gets older; fewer working-age people are available to enter the workforce, and production tends to advance slowly. In 1995 Japan had 86.9 million people aged between 16-64. Nineteen years later, in 2014, the figure has declined to 78 million.

With a loss of 9 million working-age people (10.2% of the workforce) one can’t realistically expect the country to grow at the same level that it did in the past. Even if we account for productivity gains, the potential output growth for the Japanese economy may have decreased due to a huge loss of workers. At the same time, unless the economy can export a growing share of its GDP, the internal market will have to absorb ever relatively larger quantities of output. For this to be possible production would need to shrink or prices must decline. In this context, sluggish growth and deflation are not a disease but rather a cure to a demographic disease.

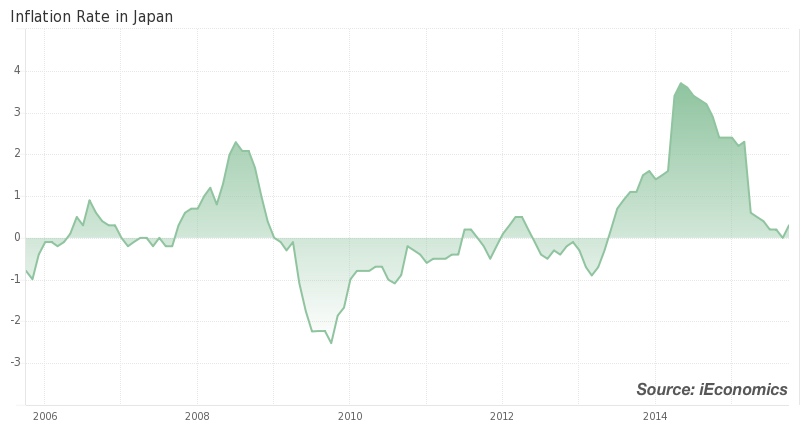

When that happens there are only two sensible ways of dealing with it. The first is to just allow the adjustment to occur. For that to happen, the government and the central bank should accept it as being a natural consequence of structural changes in the Japanese economy. Devaluing the yen may help in the short term, as may purchasing assets and messing with corporate taxes. But none of these can solve the problem permanently and that is why Abe has been tweaking his plans so much during the last three years. In his last revision, Abe added a few more arrows to his already large quiver, with the best of them being a bold promise to increase nominal GDP by 20%. During his tenure he has thus far been able to lead the economy to accumulated real growth of 2.4% while consumer prices have risen by around 4% (in 3 years). Not only are the numbers unspectacular but they’re also fading out. Part of the consequent inflation was due to the rise in consumer taxes from 5% to 8% in April last year, but as predicted by Milton Friedman long ago, such an effect is not permanent. Inflation has been decreasing abruptly since that point and the CPI is currently at the same level it was in July 2014.

Real GDP rose by 15.5% between the end of 1995 and Q3 2015, while the working age population shrank by 10.2%. Based on these numbers I would say such a performance has been quite an achievement. Because the Japanese economy is flexible enough, prices decreased to absorb the excess production. If the Japanese economy wasn’t flexible enough, real GDP would have declined and the economy would be living a long-lasting recession. Unlike what many think, this adjustment is natural and we shouldn’t blame the economy for this, nor should we apply medicine to a healthy economy. Don’t blame the Japanese consumer for saving too much. Faced with increasing living standards, an increase in the savings rate and a decrease in interest rates are natural. As the Austrian School would put it, the decreasing interest rate is a green light given by savers to move the economy towards more roundabout methods of production – i.e. creating more capital goods that take time to develop. Savers don’t mind waiting longer for a return on their savings.

Real GDP rose by 15.5% between the end of 1995 and Q3 2015, while the working age population shrank by 10.2%. Based on these numbers I would say such a performance has been quite an achievement. Because the Japanese economy is flexible enough, prices decreased to absorb the excess production. If the Japanese economy wasn’t flexible enough, real GDP would have declined and the economy would be living a long-lasting recession. Unlike what many think, this adjustment is natural and we shouldn’t blame the economy for this, nor should we apply medicine to a healthy economy. Don’t blame the Japanese consumer for saving too much. Faced with increasing living standards, an increase in the savings rate and a decrease in interest rates are natural. As the Austrian School would put it, the decreasing interest rate is a green light given by savers to move the economy towards more roundabout methods of production – i.e. creating more capital goods that take time to develop. Savers don’t mind waiting longer for a return on their savings.

But the Japanese weren’t happy with deflation and slow growth and elected Shinzo Abe to change their economic fate. Abe forced the central bank to engage in bold monetary stimulus. The programme has been so bold that the BoJ is currently purchasing assets at a total annual pace of around 80 trillion yen. For some time the programme was working well. But, suddenly, inflation started fading out again and the BoJ decided to enhance its programme with an increase in the pace of asset purchases (last year) and an extension of the duration of its bond purchases plus a 300 billion yen per year of equity purchases (over a week ago). The BoJ is fast depleting its box of tricks while just achieving modest results with inflation.

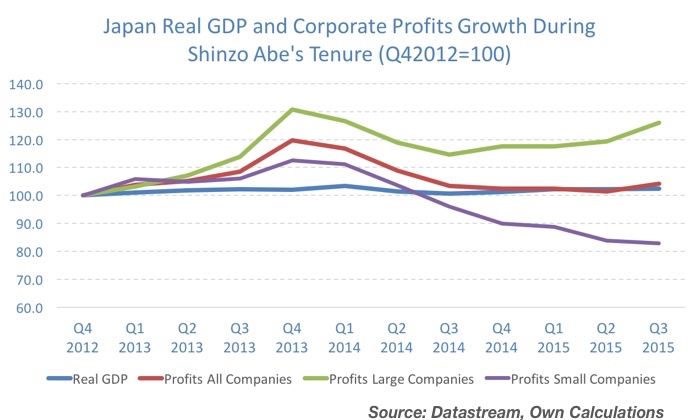

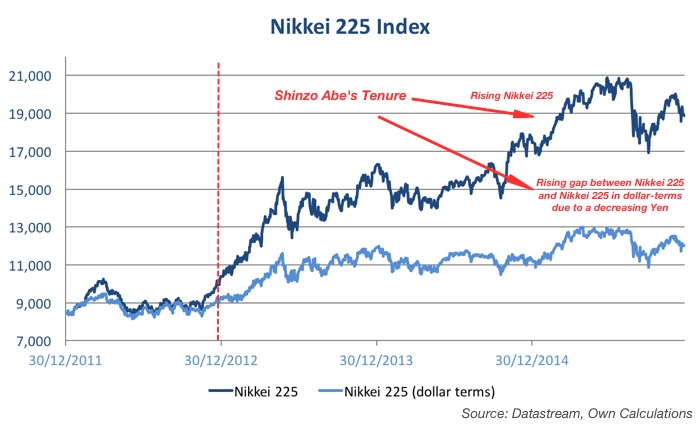

Monetary easing has been effective in pushing equity prices higher and the yen lower, as the BoJ was attempting to boost exports through the exchange rate channel and boost consumption and investment through a wealth channel. But while the central bank has been effective in boosting asset prices, the transmission mechanism still fails to deliver final results in GDP and prices, which is principally because the effects that derive from monetary policy don’t flow uniformly through the economy. The following graph makes a point in showing how differently corporations can be affected by the boldest arrow of Abenomics – monetary policy. Since Shinzo Abe came to power at the end of 2012, corporate profits rose 10.9%, but the figure grows to 38.6% for larger companies and falls to -15.9% for smaller companies. There is a massive redistribution of income between the largest companies and the smallest ones.

While redistributions occur, one also has to wonder whether the increase in asset prices is creating an asset bubble in an economy where there is no organic growth…

At times, I wonder whether it wouldn’t be easier to just drop the money from a helicopter so that the entire population can get a share of it instead of relying on a few transmission channels that end in higher corporate profits, higher dividends, more share repurchases, and no investment and consumption.

First in September and then a few days ago, Abe restated his arrows programme to now concentrate on social security and other social issues. He acknowledges that Japan has an ageing population problem and that there is a need to increase the working age population. For those goals, Abe has said the government will give cash to the elderly poor and build child-care and elderly-care facilities to help people enter and stay in the workforce. Japan is a country where people work long hours but many women are left outside the jobs market. Bringing those women into work is thus a natural policy goal. But these new arrows can only massage the current conditions and help the economy grow just temporarily.

Shinzo Abe and many economists fail to understand the nature of the Japanese problem and therefore prescribe the wrong medicine that is based in large doses of monetary easing to drown the deflation symptom. In my view, deflation isn’t a problem, but a decreasing working age population is. At this point Japan should pursue just one goal: it must halt and reverse its ageing process. And that may be accomplished with just one arrow: promoting immigration. One wonders that with so many refugees looking for a new start, Japan could promote itself to the Syrians. By allowing them to enter the country, Abe would hit three targets with a single arrow: (1) he would solve its ageing problem; (2) he would save Europe from a terrifying immigration crisis; and (3) he would give a new hope for Syrians. In the end… he would be a hero!

Comments (0)