Emerging markets are the victims of central banks

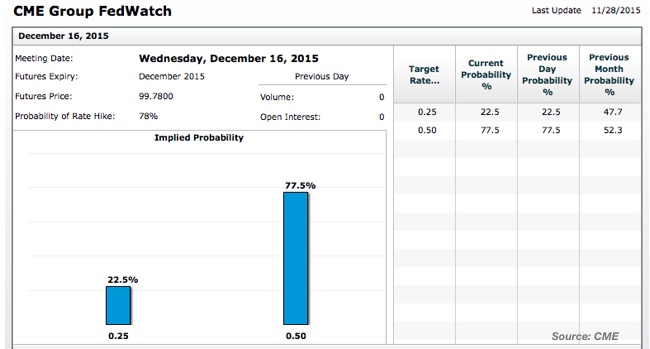

After more than a decade of easy money, the emerging world is nearing a downturn (if not a collapse), as the Federal Reserve is threatening to cut off the fuel that for years has fed skyrocketing corporate debt levels. Investors are anxiously awaiting the outcome of the next FOMC meeting, scheduled for December 16, to confirm what is already a 78% probability: the FED will hike rates by 25bps. But while investors now see a hike almost as a certainty, they had widely disregarded it for years. Investments have been made, as if rates could stay low forever. The world seems to be upside down in terms of rationality: on one hand, there is a central bank promising to deliver a 2% inflation level; while on the other, investors are willing to purchase a 10-year German bond yielding less than 0.5%. The madness is encapsulated by the fact that some investors are even prepared to pay the Swiss government to lend it money for 10 years, or to bid up the prices of a Stockholm apartment without ever visiting it. With investment decisions being taken so lightly, the latest data on EM defaults should not come as a surprise: EM defaults just hit their highest level in six years, as corporations took on too much debt over the last few years. This situation is concerning, in particular because China is slowing and the FED is about to hike rates. A currency crisis is an open possibility.

While sovereign debt was a main issue in developed countries over the past few years, corporate debt will be at the root of the next crisis in emerging economies over the years ahead. Government spending has been contained everywhere, as governments became wary of the negative impact high debt levels could have during economic downturns. But this view was not shared by corporations, which, stimulated by low interest rates and increasing aggregate demand, just took on ever growing debt levels. As always, when rates are low and economic performance is good, no one sees the risks of a reversion. Debt grows without any limits because the rise in demand obfuscates the increase in debt levels, due to the increase in corporate cash flows. While corporate revenues are increasing, debt becomes less of an issue; but as soon as revenue growth stalls, corporations need to refinance or sell their illiquid assets. In an open global economy where money flows freely, corporate leverage is a concerning matter because companies are exposed to massive inflows and outflows of money, which are often just seeking the best yields. These flows of money are not the consequence of greater domestic wealth creation, but rather the consequence of a central managed interest rate that creates speculative movements. At the first sign of smoke or when rates are expected to increase in the home country, the direction of the money flow is quickly reversed. When these inflows remain in place over an extended period, they contribute to a massive increase in leverage, as corporations benefit from a reduction in borrowing costs due to the wide availability of funds. But then the trouble begins when the supply of funds starts shrinking, leading to a sudden rise in borrowing costs.

With the developed world experiencing very low rates of return due to central bank intervention, investors demanded anything that was delivering a positive return elsewhere. The higher yields offered by EM corporate bonds were seen as a golden opportunity for investors seeking yield. At the same time, corporations also saw a great opportunity to expand production, as EMs were growing at a fast pace. The mix of opportunities allowed corporate debt to increase at an unprecedented pace. According to data provided by the Institute of International Finance (and accessed through the WSJ), corporate debt has risen fivefold over the past decade, totalling $23.7 trillion earlier in this year. But this rise has not been proportional, with the EM getting a larger share than the developed world, and with Asian countries experiencing a growth of non-financial corporate debt to 125% of GDP from 100% five years ago. A scenario combining very low borrowing costs with a fast-growing China helped this trend unfold. But, at a time when the FED is planning to hike rates and China is changing from an investment-based economy to a consumer-oriented one, what will happen to EMs where debt levels were excessively increased?

The first shocks have already been felt. As a result of slowing growth in China, commodities are in one of the worst bear markets ever. The prospects for slower growth in China quickly led to the erosion of demand expectations for commodities. In a list where I track the prices of 36 commodities, I can see that 34 show a 1-year percentage change in the red. Only cotton (+6.9pc) and cocoa (+6.6pc) seem to have survived the Armageddon. The declines are huge for the time period: Gold -5.6pc, copper -30.9pc, aluminium -33.7pc, iron ore -36.7% and crude oil -40.2pc. The prospects of slower growth in China mixed with a rising dollar hit the price of almost every raw material on earth. This downtrend doesn’t seem to be a price correction, but rather an adjustment to a new reality. With China demanding ever more commodities, corporations in commodity-producing countries engaged in massive levels of leverage to finance new projects and extract more raw materials. After all they could always sell the extra production to China! With commodity prices rising fast and borrowing costs remaining low, such investment was seen as relatively safe. But then, when the economic situation changed, these companies quickly accumulated inventories. In an industry where investment decisions take years to produce effects, the price is the main adjustment tool. This explains the crash in prices we have observed so far. Over the next few years prices are expected to stabilise, as production cuts start being felt. But in the short to near term the decline may continue, as inventories are still very high. Many companies (mostly in EM countries) will see their cash flows shrink and won’t be able to honour interest payments.

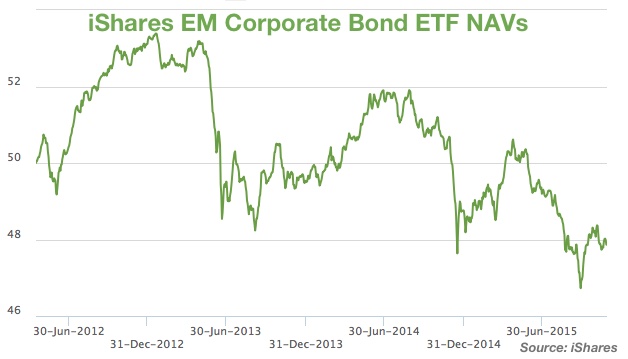

According to Barclays, the default rate on corporate high yield debt over the past twelve months reached 3.8pc, which compares with a 0.7pc level just four years ago. Defaults are increasing as a consequence of a lack of aggregate demand growth and rising interest rates. EM bond funds are too exposed to the lack of China growth, to the increasing interest rates, and to the commodities price collapse. The outflow of money has been huge and NAVs of ETFs tracking EM corporate bonds are collapsing.

The scenario depicted above is not new. The FED long ago attempted to hike rates, which led to a severe outflow of funds from emerging markets. At that time, Ben Bernanke ended up retreating and the stampede was prevented. But the quick reversion he triggered in money flows comes with a lesson: the monetary policy conducted by developed countries is not the success Ben Bernanke would like us to believe it is.

Monetary policy seems to create huge imbalances, far beyond a country’s borders. When policymakers later attempt to normalise policy, severe consequences are felt. A decrease in policy rates may prevent a liquidity crisis from creating a full-blown crisis, but it cannot generate growth without creating huge economic distortions. The FED often points to improvements in the jobs market and increases in growth, but it ignores the disconnect between asset prices and fundamental value, the increase in leverage in EM due to the hot money flows seeking higher yields, the increase in the production of capital goods at a time it already seems excessive, and an overall increase in leverage that exposes the global economy to future downturns.

Monetary policy is more about illusion than magic; it smoothes the present economic conditions at the cost of future conditions, and it smoothes the economic conditions in one country at the cost of those in another. While being an advocate of free markets, I have to admit that under these circumstances free capital flows are a problem. Whenever countries like the US or China expand their stock of money in an excessive way, they create a bubble that extends to other countries. For smaller economies there is not much of a choice. They could not have prevented their economies from taking on too much leverage without imposing capital controls. But the final result would have been bad as well. The only way out is by limiting central bank interventions everywhere. A few years ago we found that we needed monetary policy to be out of government reach; we are now in the process of finding it should be out of anyone’s reach.

Comments (0)