Don’t expect big gains from the FTSE in 2017

If you had decided to double up your exposure to the London stock market at the beginning of last year then you would have done well in 2016. The FTSE-100 was up by 14.4 percent on the year, confounding the economic realists (like me) and the Brexit doomsayers (not like me). Though, if you were a US dollar-based investor you did not do so well; in fact, given Sterling’s post-Brexit devaluation, you would have been down by around four percent.

The New York markets did even better, surprising us all with the end-of-year Trump Bump – but that is another story. Autre pays, autre mœurs as the French say.

Now the FTSE ended 2016 at an all-time high (and New York was not far off its historic peak). Such giddy moments demand a certain amount of sober reflection by sanguine investors.

Are the forces powering this upswing sustainable? Will the bulls continue to outrun the bears? Where exactly are we in the economic cycle? What are the major downside risks for the UK stock market right now?

I’ll try to answer these questions in a moment. But first let’s consider that the FTSE-100 closed just shy of 7,000 on Millennium Eve (31 December 1999) – that was 17 years ago – and only managed to regain that level in the spring of 2015.

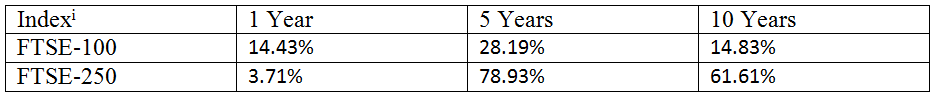

With that in mind London’s performance does not look so great. In fact, I calculate that the FTSE-100’s 2016 performance is almost identical to its 10-year performance. If you translate that into the annualised geometric return over ten years it is less than one percent per annum – a sobering thought. The FTSE-250 looks like a much better bet.

What’s been pushing the FTSE higher?

Of course, if you measure stock market performance to reflect re-invested dividend income, the picture is rosier: you can add a compounded 3-4 percent to the return figure, this being the average dividend yield. (Though this can be misleading as dividend yields vary over time and some companies do not pay dividends at all). But the fact is that two protected periods of stock market decline over the last 17 years, namely 2002-2005 and 2008-2012, cost investors many years of steady growth.

The FTSE-100 has been a beneficiary of the post-Brexit vote devaluation of the Pound, which has fallen from around US$1.49 on 22 June to about US$1.24 at year end or by just under 17 percent. Most of the constituent companies in this index have huge foreign currency income streams which are now worth more in Sterling terms.

Frankly, the FTSE-100 is largely detached from the UK economy and a better gauge of UK economic sentiment is the FTSE-250. This was up over the calendar year 2016 by a much more modest 3.71 percent.

Frankly, the FTSE-100 is largely detached from the UK economy and a better gauge of UK economic sentiment is the FTSE-250.

The economic news flow in the UK has been remarkably positive of late. Since the New Year began there has been good news for both the manufacturing and the service sectors and the UK has the best growth outlook for 2017 of any G-7 big economy.

On 05 January the “all-sector” Markit/CIPS services Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) came out at 56.2 for December, up from 55.2 in November – the highest level since July 2015[ii]. Anything above 50 indicates future expansion; a level of 56 is exceptional. Earlier this week, surveys in the construction and manufacturing sectors indicated a similar pattern of sustained growth.

The UK, uniquely in Europe, can now boast 16 consecutive quarters of positive growth. The last negative growth figure was for Q4 2012; but then 2012 was an odd year, economically speaking, with a massive growth spurt of well over one percent in Q3 attributed to the Olympic Games. While this is good news, we should recall that the UK is still growing well below its long-term trend growth rate[iii] of around 2.4 percent – but then so are our major competitors.

News on the jobs front is also positive. The UK unemployment rate declined to 4.8 percent in the three months to October 2016, as compared to 5.2 percent a year earlier. This was the lowest jobless rate since September 2005, and puts the UK in the same employment league as Germany and the Netherlands – and way better than Southern Europe where mass unemployment is now endemic.

Of course, as we know, UK productivity still lags well behind our major competitors and is likely to remain a key issue of economic policy for some time to come.

The UK is still, despite uncertainty over Brexit, a highly favoured destination for foreign direct investment. McDonald’s decision to move its global HQ to London announced last month was another vote of confidence in UK PLC.

The UK is now in a consumer boom

On the downside what is going on in the UK right now looks very much like an old-fashioned consumer boom. With interest rates at rock bottom and credit easily available to consumers in plastic form, the great UK public have been on a shopping binge this Christmas. Bank of England figures show that credit card debt increased by £1.9 billion in November to a record £66.7 billion, the highest level since the Credit Crunch.

What’s more, mortgage lending has hit an eight-month high (despite rising house prices) as house buyers find the confidence to move into the housing market for the first time or to trade up. House-buying is of course closely correlated with consumer spending as new home owners tend to buy curtains, carpets, furniture white goods and the rest.

In fact retail sales are surging, growing at the fastest rate since 2002. The household savings ratio in the UK, already low by comparison with our peers, is falling further.

The household savings ratio in the UK, already low by comparison with our peers, is falling further.

Meanwhile, the trade deficit has widened to an alarming 6 percent of GDP. Despite the fact that imports are more expensive with a weak Pound, we are buying more from abroad than ever. The expected surge in UK exports has not happened.

You don’t have to be an academic economist to know that consumer booms always end in tears. In the months to come the Bank of England will come under pressure to reverse the cut in the Base Rate from 0.5 percent to 0.25 percent back on 04 August last year, which now looks like a panic measure.

In conventional terms, upward pressure on rates puts downward pressure on markets – though in the world of near-zero interest rates that relationship is more tenuous. What is clear is that there is latent inflation in the system that will surely manifest itself in 2017.

Trouble ahead

As the Remoaners constantly remind us, we haven’t actually left the EU yet. The year ahead will be dominated by what I have described as the ghastly trope that is “Article 50” and its consequences. And every time an expert declares that we shall be condemned to leave the Single Market stroke Customs Union the markets will shudder.

On the other hand, there is the view that the markets have already discounted the risks of leaving the Single Market. I’ll be explaining soon why I simply don’t think that there will be a clean, neat deal on Britain’s exit from the EU – Fuzzy Brexit, as I call it, is the most likely outcome. Uncertainty means volatility.

But then, if Jim Mellon and others are right, the Brexit drama is likely to be eclipsed by events on the ground – political and economic – in Europe. You will be reading much more about that in these pages soon.

And there is the little matter that another recession is now due. Booms are followed by bust as sure as night follows day.

Conclusion

The real problem for investors is that returns on equities overall are in long-term decline.

I would be surprised if the FTSE-100 repeats its 2016 performance this year. My best guess is that it will revert towards the long-term mean. And I’d be happy if the FTSE-250 repeats its 2016 performance which, after all, was much better than cash.

Overall, there are reasons to be cheerful about the UK economy, despite its many shortcomings, and abundant reason to suppose that the opportunities of Brexit will exceed its risks. The real problem for investors is that returns on equities overall are in long-term decline. Why that is the case is complex; but I intend to try to unpack this in the months to come.

[i] My spreadsheet is available.

[ii] See: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-38515971

[iii] This being the arithmetic average growth rate since 1945.

Comments (0)