Do Not Take A Grexit Lightly

After a roller coaster weekend in EU politics, financial markets opened Monday with increased volatility but in certain ways disregarded the political and economic implications of what happened during the weekend. The Greeks said “no” to a new bailout, Yanis Varoufakis was dismissed, the dra(ch)ma is back on the table; but still investors don’t seem worried, as they believe that either a last minute solution will prevent Greece from exiting from the Eurozone or that such an exit would not be a material concern. But there are reasons to believe that markets are underestimating the damage that can be generated in either case. Greece will be a thorn in the EU side, no matter what the final solution really is.

During the last few weeks the negotiations between Greece and its creditors have been intense, prolonged and largely ineffective. On the Greek’s side, Yanis Varoufakis has been pushing for too many concessions, not willing to accept any new austerity measures while also asking for debt relief. On the creditor’s side, a group led by the hard-nosed Wolfgang Schäuble and Jeroen Dijsselbloem has been closing all negotiation doors that allow for the slimmest reduction in austerity, let alone debt relief. With neither willing to make any concessions, it’s going to be hard to find some common ground to start building a solution and Greece is ever closer to the exit door.

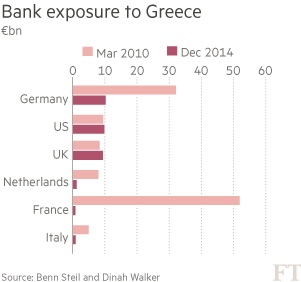

A solution that allows any relief from creditors is difficult to achieve because most of the European countries that were severely exposed to a Greek massive default in 2010 are no longer exposed to a default today, as banks in Germany, France, Italy, and Netherlands were able to cut their exposure to the country. To a certain extent, we can think of the bailout given to Greece as an indirect bailout to the above countries, because if no bailout had been given to Greece at that time, these countries would have experienced losses surpassing the amount of the original bailout. But with the bailout given to Greece, the burden was put on Greece instead. A few years later, exposure to Greece was decimated and most of the Finance Ministers on the negotiating table no longer felt an urge to cut a deal they believe being more favourable to Greece than to their own countries.

With the political will at the European level being as low as the ECB main refinancing rate, there is a risk the current Union walks towards a dead-end. One point that became clear during the current crisis was that without further progression in terms of political integration, the European Union is vulnerable in economic terms. At the Eurozone level, the lack of any political integration is even worse, as it seriously limits the number of adjustment tools to deal with financial crisis and recessions, in particular those that affect member countries unequally.

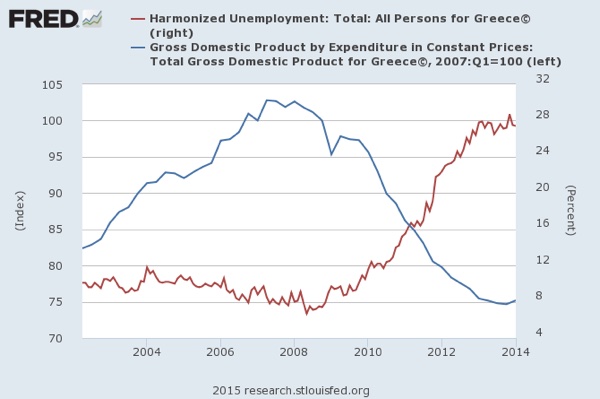

The European finance ministers hate Syriza because it brought a new wave of problems at a time when everything seemed perfect and stable, as the previous Greek PM, Antonis Samaras, was acting in line with creditors demands. But before blaming Syriza, Tsipras or the most hated of all – Yanis Varoufakis – one must understand the reasons that led to the massive change in the Greek political landscape. One cannot expect the people from a country where GDP fell 27% in a half dozen years and where unemployment is at historical highs to live peacefully, supporting its government’s actions while watching their own finances shrink every day. Most of the bailout funds helped fix a rotten banking system that has more to do with the excesses of the current monetary system than with government excesses. No government could survive the austerity imposed in Greece, in particular when it proved ineffective in solving the country’s main debt problems.

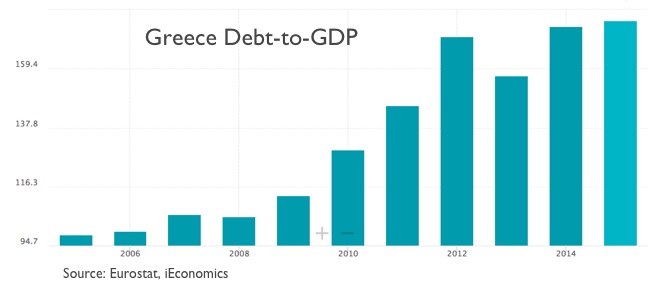

Greece was able to improve the soundness of the government budgets, even attaining a primary surplus, but that has been still not enough to significantly reduce the stock of debt, because the improvement in government deficits has always been more than offset by deterioration in GDP. The new government had no other option than to try to renegotiate the initial plan, which, without any doubt, must recognise Greece would never been able to repay its debts in full. At imposing further austerity without debt relief, the EU is just contributing to kick the can down the road for a few more years. The situation is far from being stable, and it never was stable, even though everyone seemed to be pretending austerity was good for Greece and for the peripheral Eurozone countries.

The evidence on austerity suggests Europe needs a plan B, as it completely failed at solving its debt problems. There is some financial stability achieved by Spain, Italy and Portugal, but that is the direct consequence of the ECB intervention and not of the implemented austerity measures, as debt is still at the same, or even higher, levels. Even the IMF recognises the failure, last week its chief economist, Olivier Blanchard explained that: “recent efforts among wealthy countries to shrink their deficits — through tax hikes and spending cuts — have been causing far more economic damage than experts had assumed.”

With the Greeks saying “no” to further bailouts due to the perceived economic chaos generated by the attached austerity measures and with the IMF sharing evidence on the negative impact austerity has, Alexis Tsipras has no other option than to refrain from accepting any deal that imposes an additional burden to the country and needs to bring back the debt relief idea to the table. A second option involves a stealthy and gradual exit from the Eurozone.

So far, the negotiations led by the new Greek Minister of Finance, Euclid Tsakalotos, have led nowhere, as most of the EU Finance Ministers adopt an even tougher stance against Greece and are willing to take the risk of a Grexit. I very well understand the arguments from either side and that is why I believe the EU is heading towards disgrace. By one side Greece needs to put an end to what has completely failed and will need to push for heavy concessions. If it doesn’t and after the “no” vote last Sunday, the country may experience some uprising and the people won’t accept further austerity. On the creditors side, even though Merkel and Juncker know very well how important it is to reach a deal that keeps Greece inside, many of the others like Shultz, Schäuble, Dijsselbloem and government officials from Portugal and Spain seem unconcerned with the Grexit possibility and are willing to push Greece out. In economic terms everyone knows it’s the worst thing to do, but there are many selfish political interests that push for that outcome. If Greece is relieved of part of its debts, the governments of Portugal and Spain will likely be defeated over the next election and replaced by leftist governments pushing for concessions for their home countries. Many fear such a scenario. But avoiding such a risk means creating a hole in the Eurozone and transforming an irrevocable exchange rate system into its previous fixed rate arrangement, which is a vulnerable system in particular when some financial turmoil occurs. As we have seen, it has needed much intervention from the central bank to avoid speculation from pushing the government yields too high. The famous “whatever it takes” pledge from Mario Draghi went a long way in insuring peripheral countries from the capital outflows and speculation that was making it ever more difficult for them to be kept inside the Eurozone. But imagine a future where the Eurozone had allowed for one of its members to leave at a time of crisis. At the first sign of smoke speculators will make it impossible for some peripheral countries to stay in the Euro and the ECB will be unable to do “whatever it takes” because the system would no longer be irrevocable. By other side, if Greece is a success outside the Euro, that means that under the right political conditions and with economic pressures mounting, many other countries will also ask to leave, until the Eurozone is brought down to its core members: Germany and France.

The next few days will be key and will have historical importance for the Union in Europe. The resignation of Varoufakis was an important step towards reaching an agreement. Now we would need the resignation of Schäuble and Dijsselbloem to reduce the toughness of the other side too. Then an agreement would start with asking funds from the ESM fund and repay the IMF on its existing loans to the country. Then debt must be renegotiated while its maturity extended. The ECB would by then have to step in to either keep the liquidity of Greek banks assured if they were solvent, or help recapitalise them if they were insolvent. The banking system would be restored and kept independent from the government financial soundness, the IMF put aside from the EU, and Greece left with the necessary sovereignty to decide what to do. Such a solution would be a wise one for the future of the Union…but it won’t happen; such is the selfishness of each Eurogroup member.

I expect the Euro to keep the trading range bound but I would prefer to keep my money in the Pound for the next few weeks or months (or even the Dollar). At the same time, I’m concerned with the yields from peripheral countries. For now everything seems quiet but if the crisis intensifies, the central bank will be unable to do anything and these yields will start rising again. After all, they currently don’t even reflect these countries’ risks, let alone the increased risk from a potential Euro breakup.

Comments (0)