Better ‘Hedgit’ than ‘Losit’ on Brexit

“What we should grasp, however, from the lessons of European history is that, first, there is nothing necessarily benevolent about programmes of European integration; second, the desire to achieve grand utopian plans often poses a grave threat to freedom; and third, European unity has been tried before, and the outcome was far from happy.”

– In Statecraft: Strategies for a Changing World, Margaret Thatcher, 2002

Two Brexits in less than a week is probably too much with which to contend. First, it was the Remain/Leave referendum held on June 23rd that saw the Leave vote unexpectedly clinch victory from the jaws of defeat; second, it was the shocking loss of the English team against Iceland that sent the national team home prematurely. However, the only real Brexit so far has been that of the England team from the Euro championship – the UK’s exit from the EU will take time, patience, and may still yet be averted.

As suggested by Margaret Thatcher above, European integration is a utopian process that will face several challenges that could quickly derail it. It has already happened in the past and it may well happen again. Just two or three years ago we almost saw Greece leave the Eurozone, and today we’re facing the possibility of Britain leaving the whole European Union. While the European bloc has survived referendums and turmoil, this time the British said no to it, as they voted 51.9% in favour of Leaving. In Britain, the EU is seen as a threat to free trade, sovereignty, and personal freedoms. And, unfortunately, the people seem to be right. The Union has turned itself into a bureaucratic monolith, led by sub-par politicians imposing one-size-fits-all policies that have turned recession into depression.

But, if there is failure within the EU, it mainly stems from two areas: the euro and the current EU leaders. Much less from the Union process itself. The Euro is a failure because no currency bloc can be built without a compensation system able to selectively deal with regional differences. Europe will always be a heterogeneous group, made up of different cultures, languages, and living standards. This will always translate into differences in economic performance that must be dealt with through the use of regional tools, not European bazookas. Meanwhile, Europe currently lacks real leadership in a bloc managed by a bunch of quasi dictators trying to impose their own interests on others. Agreement has turned into imposition, and Euroscepticism has turned into Euroloathing. It should come as no surprise that the British see Europe as a burden rather than a boon. Others may well follow.

Nevertheless, I still believe there’s something to lose when leaving. As I said, the main problem is related to the euro project and the Union leaders. Through being inside the EU, Britain would have the strength to force a political change to improve the European future. Through being outside, Britain will live in the shadow of this bloc (while it lasts) because it will always depend on its access to the single market. A leader like Margaret Thatcher would possess the leadership capabilities to force through changes that would benefit the Union as a whole. Such a result would be preferable to going it alone.

But, unfortunately, the main problem is that current leaders are much weaker than that and completely incapable of dealing with Merkel and Hollande on equal terms, in a manner conducive to changing the Union’s future. Britain once was able to improve the free market and increase the Union’s efficiency, but recent policy, pursued by David Cameron, has been principally about what can be extracted from Merkel and Hollande, rather than leading the Union anywhere. Under such a scenario, the British public was left with no other option than to vote to leave, which has led the country into a severe political crisis. It is now time for the people to find a real leader – one capable of guiding Britain towards economic and social success.

With my comments on the European political outlook in mind, it is time to look at the investment perspective. First of all, let me reinforce the idea that Britain is not out yet. I think the final decision regarding Brexit has not yet been fully taken, no matter what politicians may say and no matter the result of the referendum. During the next few months, we will witness dozens of risk events that will guide the future on that matter. We still don’t know yet. And because we don’t know, our investment options should be hedged extensively.

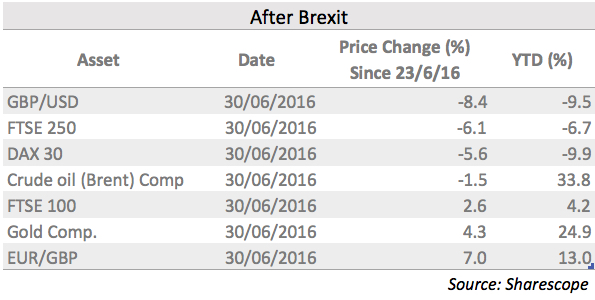

Before the Brexit, the pound rose frenetically, only to then suddenly decline once the result of the referendum became apparent. Equity markets around the world experienced heavy losses. The FTSE seems to have done much better, but when its performance is converted from local currency into euros or dollars the picture looks grimmer, as the pound has suffered a loss of 7% against the euro and 8.5% against the dollar.

A few weeks before the Brexit I picked up the FTSE 100 on a long position. I’m sticking to it. One good thing about this blue-chip index is that it is heavily weighted towards foreign currency earners, which benefit from a weakening pound. What I would stay away from, at this point, is the more domestically-oriented FTSE 250. While the FTSE 100 is up 2.6% since June 23 (just before the referendum), the FTSE 250 is down 6.1%. Instead of being an opportunity, the difference in performance seems justified by the current fundamentals. The outperformance of the FTSE 100 over the FTSE 250 will likely continue while the Brexit doubts remain. For someone willing to reduce market risk, a good pairs trading idea would be to buy FTSE 100 while selling the same amount of FTSE 250. Such a trade would benefit from the consequences of Brexit over the domestic economy while erasing market risk.

Still on the equities side, I believe the DAX 30 is a buy. The index is down 5.6% due to the Brexit results but I’m seeing potential for a reversion of the accumulated losses. I’m adding the iShares Core DAX UCITS ETF (EXS1.DE), currently trading at €84.80. If the pound eases a little more, there’s an added benefit of trading in euros.

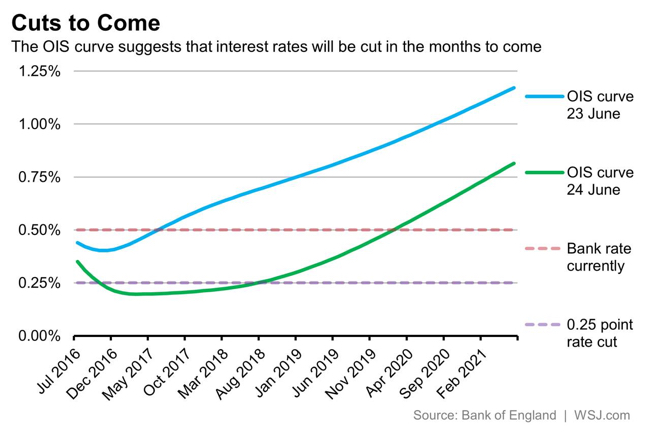

Regarding the future, I’m a little concerned in particular with the UK current account. The deficit stands at near 7% of GDP and has been financed with a large inflow of investments to the country over the years. I fear that once out of the EU, or once this whole Brexit process is known with more certainty, the UK financial market will lose competitiveness. If that happens there are only too solutions: the first is to allow the pound to adjust, the second is to raise interest rates. The market is expecting a rate cut from the BoE, as reflected in the instantaneous overnight index swap forward curve (OIS), but would it be reasonable to expect further cuts in the future?

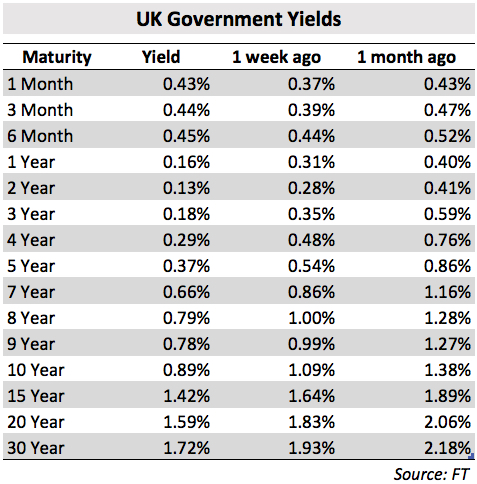

Carney already promised an extra liquidity package to deal with Brexit. But I really don’t see any options other than a massive decline for the pound or an increase in interest rates as a way of dealing with the current account deficit when the UK market loses attractiveness. This seems to be a worry that few are discounting right now. Those saving for a pension have here a reason for concern. Gilt yields are on a downtrend, as the market expects rate cuts and an ultra-loose monetary policy, but such a policy may have disastrous consequences for future inflation, which would mean a massive loss for bondholders. To hedge my portfolio, I am adding a short on GILTS through the UK Gilts Short Daily ETF (XUGS), currently trading at 8,487.15p.

Comments (0)