The Death of Bonds

As seen in the latest issue of Master Investor Magazine

“The Federal Reserve Bank buys government bonds without one penny…”

– Congressman Wright Patman, Congressional Record, Sept 30, 1941

Unlimited Intervention

Over the last few years, investors have been trying to front run central banks by purchasing bonds, in anticipation of huge price increases as the result of the heavy demand that stems from central banks as they unfold large-scale asset purchase programmes to boost inflation levels. It all started in the US, where Ben Bernanke spent trillions of dollars purchasing government bonds and mortgage-backed securities in an attempt to reduce bond yields and thereby spur businesses and individuals to borrow, invest and spend more. But as the global economy is more interconnected than ever before, the same policy was followed the world over, which pushed global yields down and bond prices up. Even Japan, which was already running a decades-long expansionary policy, decided to become even bolder in its action.

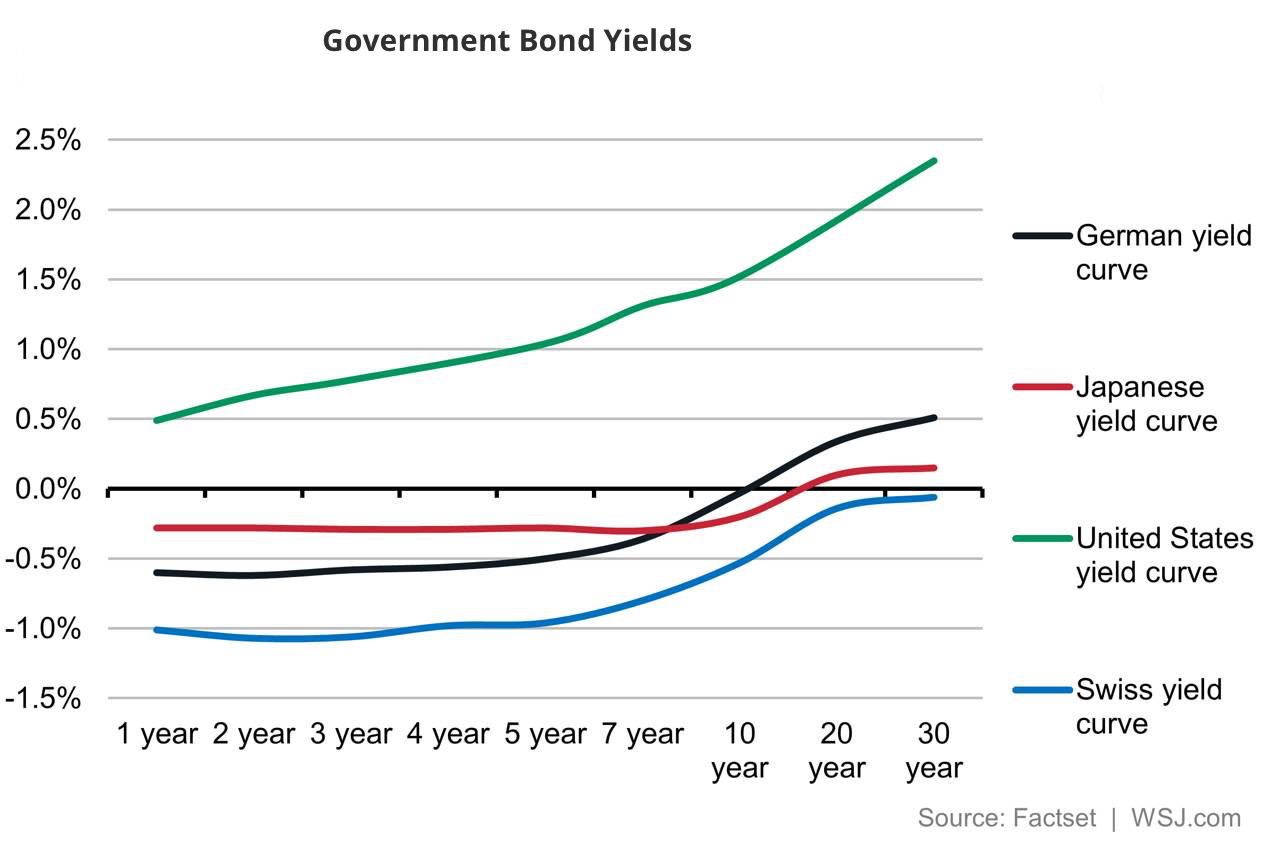

Those who purchased European bonds ahead of the ECB over the last few years have certainly experienced massive capital gains, as yields have been pushed down by the intervention of the central bank. But at a point when yields are under water for maturities up to 10 years, there is a growing concern that we may be reaching the lower bound. We know there is a point at which people would prefer to keep the money under the mattress – we don’t know exactly where that point lies, but we do know we’re approaching it.

Central banks have taken centre stage over the last eight years and have exceeded governments in terms of market intervention. Current bond yields are not the result of rational, market-driven forces but rather the result of central bank intervention coupled with a rigid and prescriptive legal framework that forces some institutions to purchase assets at irrational prices. Purchasing bonds at these irrational prices is certainly not the best option, but while bonds are way overvalued, the current price level hardly represents a short selling opportunity. This irrational exuberance is not going to end soon, as inflation is still dormant, and central banks will push harder for it by increasing their current rescue programmes and using new tools. In my view, investors looking for safe havens should skip bonds at this point, while those looking for a shorting opportunity should be wary given the prospects of further interest rate cuts and asset purchase programmes.

Three Groups of Bond Investors

There are three main groups of bond investors: legally-constrained institutional investors, speculators, and risk-averse investors. The interaction between them helps explain why yields may remain at irrational levels for a long period of time and identify the boundaries for price action.

As the name suggests, legally-constrained institutional investors are large institutions that, one way or another, need to purchase safe assets due to legal constraints or statutory imposition. In general, these institutional investors only purchase the safer assets, usually government bonds and highly rated corporate bonds. Central banks, for example, hold government bonds as foreign reserves, without any care for yields or prices. The central bank of Saudi Arabia is one of the top purchasers of US Treasury Bonds, as it needs these assets to maintain the peg of the riyal to the dollar. Because the main objective is not to make a return on bond holdings, a central bank is usually insensitive to bond prices (or yields). Central banks also keep bonds on their books as the result of their open market operations. The ECB requires banks to pledge collateral to lend them money. This collateral is often composed of government bonds. Additionally, central banks sometimes purchase large quantities of government and corporate bonds, which they keep on their balance sheets until maturity. Again, the central bank is relatively insensitive to prices (and yields), as its demand is not driven by market forces.

But the central bank isn’t the only institutional investor demanding bonds for legal or statutory reasons. As I mentioned above, banks need bonds to pledge as collateral for the loans they take from the central bank (and from the money market). They are also required by BASEL rules to carry safe bonds on their balance sheets. Insurance companies and pension funds also purchase safe bonds in order to match their liabilities. No matter how irrational the price of a bond is, these institutions have no other option than to purchase the ‘safer’ assets.

The second group of bond investors is composed of those who purchase bonds because they think there will be a greater fool purchasing from them at a later date and at an even higher price. Rationally, there is no reason to purchase a bond at a negative yield, because you are paying for the privilege of lending. By keeping the money under the mattress you get a higher return. But because of group one, group two may opt to purchase the irrationally priced bonds, as there is a greater fool that will purchase the bonds from them at an even higher price. This group just attempts to front-run central banks.

The third group is made up of anxious, risk-averse investors, who tend to purchase only the safest assets. Most government bonds are seen as safe assets in the sense that credit events are unlikely. People often ignore inflation and taxes and end up demanding assets that seem safe because all cash flows are usually paid by the issuer, but which lose purchasing power over time due to the low yields not covering inflation and taxes. The existence of group three is one of the reasons why central banks have been failing to deliver on inflation levels.

No matter how low yields are, there will always be a group of investors that only wish to hold cash and government bonds. That being true, lower yields just prompt this group to increase its savings rate as it desperately attempts to maintain its future level of savings.

Massive Losses on the Horizon

The above reasoning helps us to understand why there is a bubble in the bond market and why it won’t burst right now. Long-term investors saving for a pension should keep their money away from this market, but it may not be the best time to short bonds, because central banks won’t stop before boosting inflation to at least 2%, meaning that, in the short term, we may see bond yields become more deeply negative. With the US delaying the next hike and revising the path of hikes to be softer than previously anticipated, I expect Europe and Japan to further expand their asset purchases and eventually cut interest rates. With so many bazookas trying to hit the target, sooner or later, inflation may just end up rising. If that happens, bond investors would experience significant losses.

Concerned with the decreasing returns they’re getting from fixed income, many investors are turning to longer-maturity bonds. The demand for longer-maturity government bonds is increasing and some governments are now issuing 30-year, 50-year and even 100-year bonds. The longer the maturity, the higher the yield offered. But investors should realise that the higher yield is a compensation for the higher risk incurred. The loss that can derive from a small change in interest rates increases with distance to maturity. Longer-dated bonds are exposed to a significant interest rate risk. At a point in time when yields are at their lowest ever, investors should avoid investing in these longer-maturity bonds as a way of recovering the lost yield because they will most likely end up losing purchasing power over time.

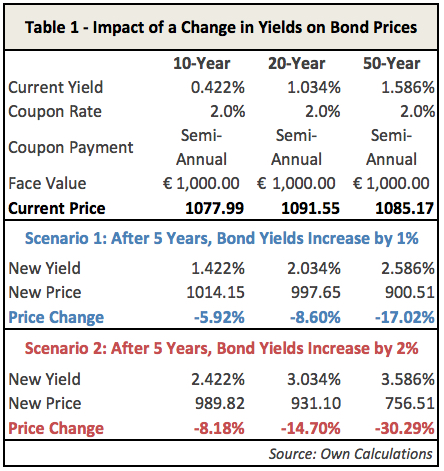

Table 1 shows the impact of a rise in yields on bond prices. The base case considers three bonds, with different maturities, all paying coupons semi-annually at the rate of 2% per year. The yields are 0.422%, 1.034% and 1.586% for the 10-year, 20-year and 50-year bonds, respectively. These yields are approximately those currently on offer on French government debt.

An investor planning to keep the bond until the maturity date (or for a long period of time) is willing to accept, at the very least, a return that maintains purchasing power over time. If interest rates rise, the investor loses money, no matter whether he decides to keep the bonds or to sell them. If opting for the first option, he would keep the yield on the bond, while the market is offering something more. This opportunity cost is similar to a loss. If opting for the second, he would have to accept selling the bond at a discount. One way or another, a loss is incurred.

In the example depicted in table 1, if after five years the yield rises by 1%, the price of the bond will decrease by 5.9%, 8.6%, or 17.0% depending on the bond maturity being 10-year, 20-year or 50-year respectively. If the increase in yields is 2%, the respective declines in price are 8.2%, 14.7% and 30.3%.

While this situation may appear unlikely, allow me to point out here that the main goal of the ECB (as well as for most central banks around the world) is to keep the inflation rate around 2%. The central bank will do anything to boost inflation to that level. While it may fail to deliver on its intents over a period of 2-3 years, it is more likely to achieve it over a longer period. The shorter-maturity bonds offer ridiculously low yields but the longer-maturity bonds are heavily exposed to interest rate risk. In the example depicted in table 1, the 50-year bond suffers a loss of 30% when yields rise by 2% after five years. Even if the increase in yields occurs only after 10 years (not reported in the table), the loss would then be equal to 28.5%.

Because of the elevated risk that comes with longer-term bonds, I would avoid them, particularly at a point when central banks are playing in the opposite direction. While austerity has been the main fiscal policy driver for the last seven years, the situation may change in the near future if monetary policy continues to fail at delivering the expected results. We have already heard some central banks mention the concept of ‘helicopter money’ as a new tool and we will hear about boosting fiscal policy too. In my view, the risks of overshooting inflation targets are currently higher than the risks of a deflationary spiral.

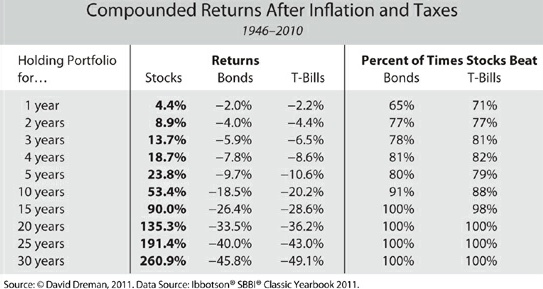

There is an additional argument playing out against bonds. While bonds are usually said to be safer assets than equities because returns are less volatile, the real risk measure for a long-term investor isn’t volatility of returns but rather the deviation of returns from the investor’s objectives. Someone saving for a pension is looking to achieve a positive return after inflation and taxes are accounted for, after 20, 25 or 30 years. So, when evaluating the best distribution of funds between equities and fixed income, what an investor wants is to maximise the odds of hitting his target return. In this sense, the real risk of investing in bonds is the odds of equities outperforming them.

According to thorough research presented by David Dreman in his book “Contrarian Investment Strategies: The Psychological Edge”, in the US market during the period 1946-2010 equities have on average significantly outperformed bonds and treasury bills over almost any time interval. For a one-year interval, for example, equities outperformed bonds 65% of the time. As the time interval is enlarged, the odds of equities beating bonds and treasury bills increase. In a 15-year interval or greater, stocks always beat bonds.

Final Remarks

The fixed income market has traditionally underperformed equities over almost any time interval. With bond yields currently at their lowest level ever and historical data greatly favouring equities over fixed income, it’s hard to find any value from investing in fixed income at this point. Those needing to save for a pension would be better off investing in equities or real assets. At least that way they’re protected from any surge in inflation.

Although the world is now preoccupied with the deflation threat, average prices have historically drifted higher over time. With all major central banks around the world colluding to boost prices, investors should avoid relying on the assets that suffer the most with accelerating inflation. Nevertheless, I don’t favour shorting bonds either, because I believe central banks will cut interest rates further and will continue to drive yields down in the short- to medium-term.

Comments (0)