The Silent Rise of the Prospect Generator Model

The Silent Rise of the Prospect Generator Model

Data compiled by Master Investor & Global Mining Observer, covering 10 years and over a dozen different companies, shows that one overlooked corner of Canada’s mining industry is sitting on C$120m of cash and a record number of properties

When geologist and gold explorer Brent Cook went to work for mining financier Rick Rule in California in the 1990s, he was offered an unusual pay package.

“He didn’t pay me much, but he gave me a $200,000 line of credit that I could use to buy whatever I wanted in the mineral sector,” Cook recalls, “and I could keep the profits after a bit of interest. What a great deal right? Well within a year, I was $90,000 in a hole.”

The lesson was difficult to forget: companies drilling for discoveries can turn a few hundred thousand dollars into a billion of dollars of metal, but pinpointing where those discoveries will happen, even with Cook’s geological insight, is a lottery that can leave you with nothing.

1997 to 2002

Over the following 5 years, Rule, Cook and fellow broker Paul van Eeden hatched an innovative new funding model, aimed at mitigating the company-busting odds associated with drilling greenfield projects.

Rather than going for broke, issuing shares and burning through cash to fund high-cost drilling, the Kamikaze model, companies could stake land and option it on to other miners, in exchange for cash, shares, spending commitments and a minority project share.

It was a brilliantly simple solution, massively skewing the risk-reward balance. Prospect generators, a phrase Rule had lifted from oil and gas, could relinquish all of a project’s financing risk, but only part of its upside. And by building a broad portfolio of properties, all funded by other companies, they greatly increased their chances of hitting a major discovery.

It was akin to breeding racehorses and retaining a share in any future winnings, rather than raising money to buy an unproven foal.

Performance

Nearly 20 years after the model was first conceived, prospect generators remain one of the smallest subsets of the mining industry, with a combined market cap of around C$910m ($700m). But the wave of Canada-based companies that Rule and Cook agreed to finance, in exchange for following the model, have been some of the mining industry’s strongest performers.

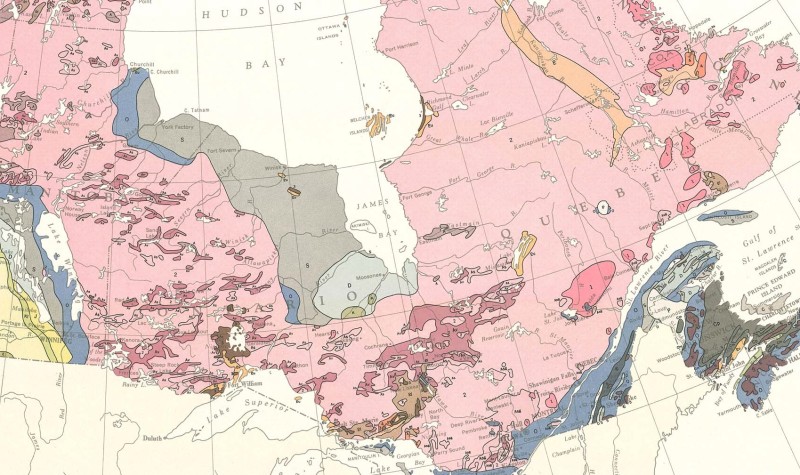

Virginia Mines, which plied the model in Quebec’s James Bay, was swallowed by Osisko Gold in a C$1.3bn deal earlier this year, whilst Reservoir Minerals, which has used joint-ventures to fund ultra-deep drilling in Serbia, is now sitting on the mining industry’s largest new copper discovery through a joint-venture funded by Freeport, the world’s largest listed copper producer.

Reservoir’s shares have risen 8-fold since 2012, versus a 60 per cent slump for Freeport and much of the wider industry.

Miles Thompson

“Everybody treats exploration like gambling,” says Reservoir’s chairman, Miles Thompson, who Cook introduced to Rule in the late 1990s. “They remember their wins, they forget their losses and they pay no attention to the risks.”

“As an exploration geologist, particularly in early-stage exploration, more than 90 per cent of what you do will fail, so why you would bet your company on one exploration play is bizarre to me.”

Reservoir has staked nearly 1,000 sq kms of land in Serbia, where Freeport is pouring over $18m into their Timok joint-venture this year, reporting blockbuster intercepts, including 179m at over 17 per cent copper equivalent. Thompson also heads Lara Exploration, a prospect generator with joint-ventures with Codelco and Hochschild Mining in Brazil and Peru.

“If one of the countries we work in shut us out, if one of the sources of capital walked away, if one, two or ten of our projects failed, it doesn’t kill the business,” Thompson says.

“Above Criticism”

“The model is above criticism,” boasts Rick Rule, though the application “is frequently lacking.” The commonest error, he says, is staking projects but failing to vend them into joint-ventures, tempting companies to drill them in-house, whilst the warning sign is a company where salaries exceed spending by third parties, unwinding the model’s advantage.

“We’ve had some targets that just beg to be drilled,” says Brian Dalton, founder of Altius Minerals, the model’s earliest proponent, “but when you raise money and drill a hole and it doesn’t work, there’s nothing left. There’s no residual value whatsoever.”

Altius has spent $16m on exploration in the last 10 years, versus $370m spent by its joint-venture partners, generating dial-moving discoveries in uranium and iron ore. Its shares have rocketed from C$0.40 to C$13.04 since listing in 1997.

New Ground

Prospect generators remain poorly defined as a sector, but data compiled by Global Mining Observer shows that as a peer group, they are sitting on over C$120m of cash and a record number of properties, having used the current downturn to hoover up new acreage.

Reservoir, which picked up its Timok project after markets crashed in 2008, recently staked new properties in West Africa and Macedonia, whilst Altius has taken large land positions in Michigan and Alberta, using surplus cash to add to its royalty portfolio.

Mirasol Resources, focused on Argentina and Chile, has also been picking-up ground “that should be valuable when the market tuns,” Brent Cook says.

In contrast, the wider exploration industry is battling a financing crisis, with cash reserves “at an all-time low”, according to accountancy PwC. Revenue at drilling contractor Boart Longyear, a proxy for exploration activity, has plummeted from over $2bn in 2011 to $867m last year.

“People just don’t want to hear about the sector,” Thompson says, “but the things that you can do with a little bit of money now are going to be worth multiples in a few years time.”

“If you go to the bar for 3 years and wait for the bull market, you’ve missed it. You’re paying top dollar for everything and nobody can make any money.”

“Makes Sense”

Despite the model’s success, prospect generators remain almost unheard of in Australia or the UK. “If you try to talk about prospect generators in London, you’re wasting your time,” says one director with assets in Turkey.

But in Canada and the US, the model is steadily gaining steam. “In the 80s, I was writing about gold stocks and I just got tired of losing 80 per cent of my money,” says Maryland-based fund manager Adrian Day, one of the largest investors behind Altius, Virginia and Reservoir.

“I recognised that I’m not a geologist, I don’t have an edge in looking at a property, so I look at mining companies as businesses. Is this a business that makes sense? You can look at these companies and clearly say, this is a business that makes sense.”

Comments (0)