Big In Japan

As seen in this month’s issue of Master Investor Magazine.

“With the strength of my entire cabinet, I will implement bold monetary policy, flexible fiscal policy and a growth strategy that encourages private investment, and with these three policy pillars, achieve results”

― Shinzo Abe, 2012

16th December, 2012

It was the night of December 16th. The year was 2012. The future of Japan was about to be rewritten. Shinzo Abe appeared triumphant before the people who had just chosen him to command the fate of the country for the next few years. Disappointed with more than a decade of stagnation, the people were looking for someone willing to throw everything but the kitchen sink at the economy to reflate it once and for all. No more gradual quantitative easing, no more gradual fiscal policy, no more gradual anything. What Japan was in need of was shock and awe to revive its zombified economy. Abe promised a complete break with the past and soon start implementing what became known as Abenomics.

While the Bank of Japan (BoJ) is theoretically independent from the government, the pressure applied by Abe was so great that just four months after his election, the BoJ announced a new quantitative and qualitative easing programme (QQE) aimed at expanding its monetary base and reducing the returns on “risk-free” assets across the entire maturity spectrum. The idea was to, on the one hand, boost corporate investment, which would translate into employment creation, wage growth and more consumer spending; while, on the other hand, entice investors to replace their “risk-free” investments for higher-yield ones, which would lead to an increase in asset prices and, through a wealth effect, to more real investment, more employment, and growth. Inspired by Ben Bernanke and the US Federal Reserve, the new QQE adopted by the BoJ was aimed at creating the shock and awe that everyone was looking for and put an end to gradualist policies that were creating addiction without ever being effective.

On April 4, 2013 the BoJ announced the following measures:

- Increase the monetary base by JPY 60-70 trillion yearly;

- Purchase JPY 50 trillion of Japanese Government Bonds (JGB) yearly;

- Target an average duration for bonds around seven years;

- Purchase JPY 1 trillion of ETFs yearly;

- Purchase JPY 30 billion of J-REITs yearly;

Over the course of just less than two years, the central bank was expected to double the value of the assets on its balance sheet, which was seen as a bold step towards generating inflation and finally awakening the Japanese economy. With the BoJ injecting money into the economy, the Yen was expected to weaken and help stimulate an export-oriented recovery. While trade (imports plus exports) for the Japanese economy represent just 35% of GDP (the same figure is more than 80% in Germany); in volume terms, Japan is the fourth largest exporter in the world. If the impact on the Yen were sufficiently strong, Abe could get a significant boost for the economy from external trade.

Abe’s plan was based on a three-arrow policy, which comprised the following: 1) bold monetary policy action; 2) an active fiscal policy; and 3) structural reforms and growth strategies to promote private investment.

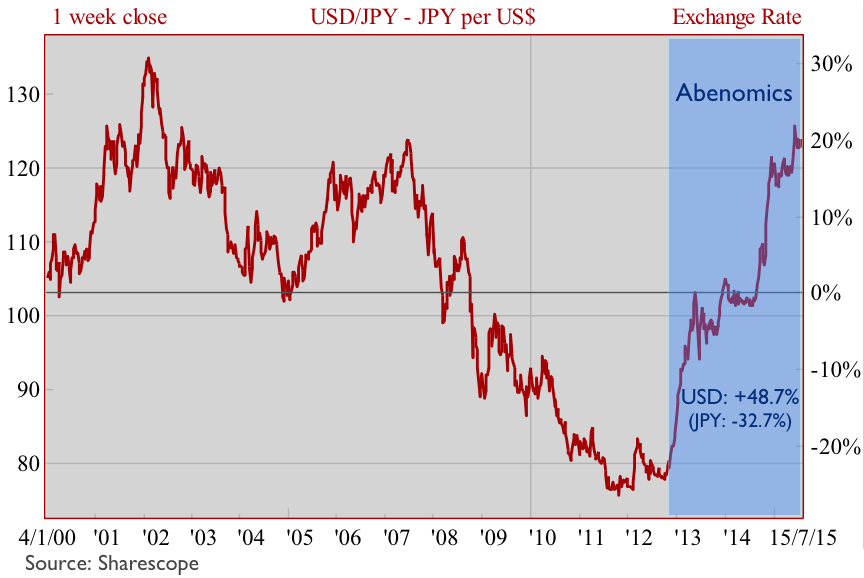

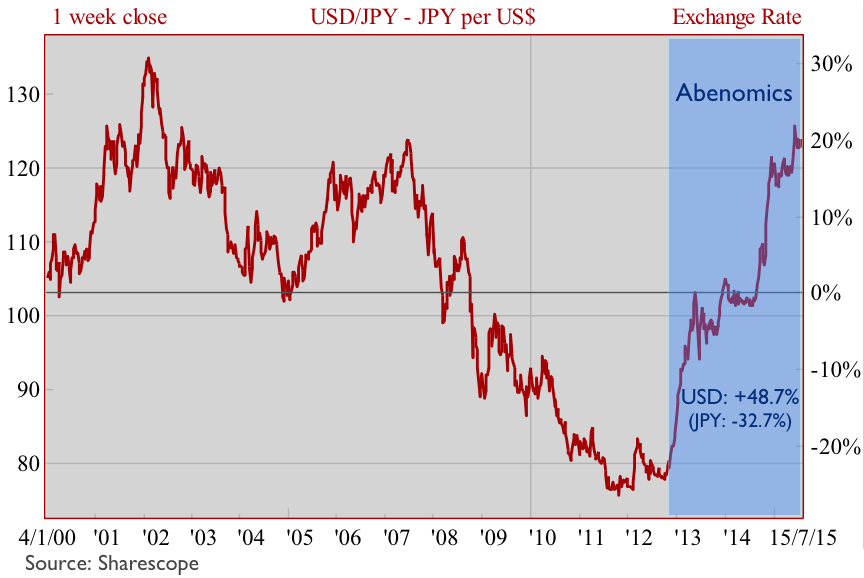

The Start of a Rebound

The reaction from financial markets to Abenomics was very positive. Japanese equities have rebounded strongly since Abe came to power (in fact the rebound started one month before as the odds for Abe being elected were already high by then). The Nikkei 225 and the TOPIX are up 112% and 107% respectively since December 16, 2012. That is a massive outperformance when compared with almost any other market and it is clear proof that above all quantitative easing leads to higher equity prices. The Yen reversed its long-term bull trend and lost almost 33% of its value against the US Dollar.

In 2014, however, with the introduction of a planned consumption tax increase from 5% to 8% (which occurred in April), GDP plunged and investor sentiment turned momentarily negative. With oil prices largely declining and negatively impacting inflation while the tax increase was leading towards recession, investors feared a derailment in Abenomics and abandoned equities. But the positive sentiment was recovered and the bull market resumed later in the year, mainly due to three events: firstly, Shinzo Abe strategically dissolved the lower house of Japan’s legislature to call a general election and through this extend his mandate; secondly, Abe decided to postpone a second planned hike in consumption tax to April 2017; and thirdly, the BoJ announced in October a second version for its QQE programme, which was even bolder than the first. On October 17th of last year equities hit a turning point, resuming the bull market to climb 40% until today, in a very strong move.

When we compare the performance observed in the Japanese equity market with the performance in the European and the US markets, we quickly realise how strong and influential Abenomics has been. For the last five years Japan tops the table of returns, and the advantage is in particular more pronounced for the last three years (or for the period coinciding with the Abenomics implementation).

In parallel, the effect on the Yen was also very strong, as the currency declined by 32.7%, 30.4% and 18.7% against the US Dollar, Pound Sterling and Euro respectively during the Abenomics period.

On one hand, the weakening of the Yen had an important impact on exports and imports, helping boost employment and growth, while pressing internal prices higher. But, awkwardly, this weakness acts as a threat for foreign investors at the time they wish to convert their profits into their original currencies. With the yen losing more than 30% of its value against the US Dollar and Sterling, the excess returns obtained from investing in Japanese equities can be severely reduced or even impaired. But when we compare the Nikkei’s performance during the Abenomics period with those of the S&P 500 and FTSE 100, we see outperformance of 61.3% and 96.8% respectively, which even after discounting for the weaker Yen, still represents massive outperformance.

What to Expect in the Near Future

While the historical returns tell us a lot about the effectiveness of Abenomics, they don’t help much when it comes to assessing the future. At this junction the question that remains is this: Are Japanese equities still worth an investment?

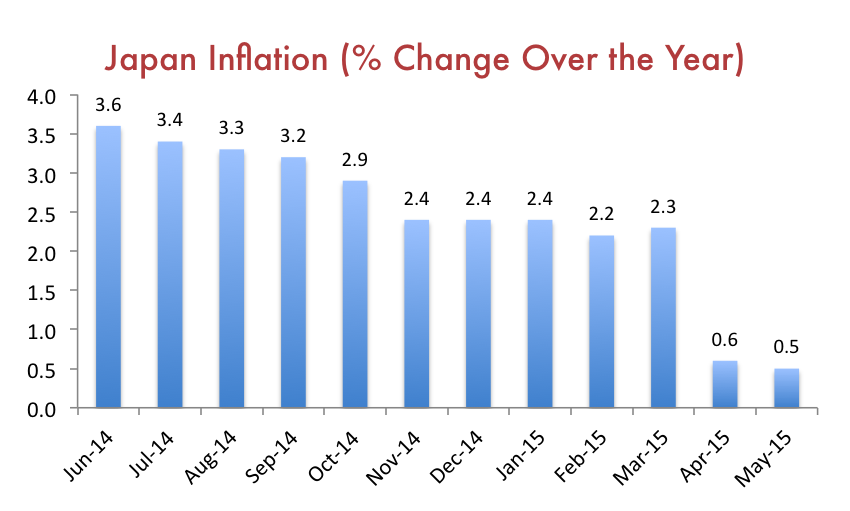

As became obvious over the past two and a half years, Abe is really serious (if not paranoid) about giving a direction to the economy. The initial steps taken in terms of monetary policy in 2013 were bold enough for us to perceive. Later, when the global economic outlook looked grimmer in 2014 and Abe feared a derailing of his main goals, further bold measures were taken. Abe dissolved the lower house and postponed the planned tax hike while the BoJ engaged in further easing. For the next few years, and as long as inflation remains below the 2% target and growth is not substantial, the BoJ will keep expanding its monetary base, now at a pace of JPY 80 trillion per year (an increase of JPY 10-20 trillion from QQE1) while purchasing JPY 80 trillion of JGB (an increase of JPY 30 trillion). At the same time the BoJ extended the target maturity for its JGB purchases from 7-10 years to 10 years and is expected to increase the purchase of ETFs and J-REITs by three-fold to JPY 3 trillion and JPY 90 billion respectively. These are very serious measures that will most likely continue to push equities higher over the next few months.

The government and the central bank want to reduce the temporary impact of decreasing oil prices on inflation and push Japan into a positive economic cycle at any cost. Fiscal soundness will be left for the future (much unlike what happens in the Eurozone where austerity comes in front of everything else). The idea is to lead companies to export more and to invest more, hence extending capacity and hiring, which thereafter is expected to contribute to wage growth and higher consumption.

While the first arrow of Abenomics unfolds, the government has also been preparing a few structural reforms that will start playing out in the near future. An example of this is the introduction of the Stewardship Code (in February 2014) and the introduction of the Corporate Governance Code (in June 2015). Under the new law, investors will find it easier to reach the companies they invest in. The law will mitigate agency costs that arise between management and ownership and hence help to increase corporate value through enhanced ROE, increased dividends and share repurchases. It is widely expected that corporate Japan will become more efficient over the next few years.

In terms of the government goal regarding stable inflation near the 2% level, I really don’t know how easily that will be achieved. In my view, when a central bank expands its monetary base through asset purchases, it creates inflation. But the inflation that is created is asset inflation, or a generalised increase in the price of financial assets and real estate, which is not coincident with the consumer inflation the bank establishes in its goals. Whether or not inflation will extend to consumer products remains to be seen. But for the sake of equity investment, it doesn’t even matter much at this point because, as long as the BoJ continues with its QQE2 programme, the pressure on financial assets and real estate will continue and thus provide investors with enhanced returns. A problem that could arise here is the risk of creating an asset bubble. But on that field Japan is in a much better position than the US, as corporate valuations are still bellow historical average and are well below the mean valuation of the S&P 500 components. The projected P/E for Japanese equities is around 16.6x while the same is around 27.3x for the S&P 500 equities. This provides a layer of safety for investors in Japan.

Additionally, while the Nikkei 225 has been outperforming other markets during the last few years, the market is still lagging behind other markets over the longer-term. If we rewind around 20 years to 1995 we find that the performance for the index has been almost flat as opposed to around 100% for the FTSE 100 and 250% for the S&P 500.

Japan will also benefit from the weakness in oil markets. While a decreasing oil price reduces inflation in the short term, and thus may negatively impact the goal of boosting consumer prices, this effect is just transitory. But a low oil price is very healthy for an economy that heavily depends on imports of oil, as it will enhance the competitiveness of export companies.

Lastly, we should also weight the differential in monetary policy, in particular between Japan and the UK and the US. A few days ago Mark Carney and Janet Yellen raised the possibility of hiking rates this year, something that is not going to happen in Japan and hence will give extra leverage to the economy through a weakening yen.

Some Final Words

At a time when the equity bull market in the US seems exhausted and Europe is in trouble, investing in Japan represents a good opportunity for investors. The bold actions Abe is willing to take are an assurance of a lasting bull market. At the same time, with projected valuations still below average and well below their US equivalent, investors have another more material reason to purchase equities: fundamental value is still above price.

There’s definitely value to be unlocked in Japanese equities, which is a good reason to go big in Japan. But remember, the Yen is under pressure and its weakness may undermine any gains. Hedging against currency risk is therefore key.

Comments (0)