BIS Warns on Global Distortions

Painkillers can help you dull the pain when recovering from an unhealthy condition to a healthy one. But when you use too much of them for a prolonged time, increasing the daily dose to unsafe levels until they miraculous cure your unhealthy condition, you may end up killing something (but not the pain). The same logic applies to our economy when we use temporary tools – ones aimed at alleviating the side effects of unhealthy economic conditions – in a permanent way. The painkiller here is the interest rate and the lower it is, the higher its dosage.

Mainstream economics accepts that the lower the interest rate, the higher the investment. The rationale is acceptable. If the cost of borrowing decreases, one may be willing to borrow more. But, in our modern economy, borrowing need not be related to investment in real assets, research and development, introduction of new technologies, and other GDP-enhancing activities. In our modern world, when the cost of borrowing decreases, it becomes less expensive to take on more risk, to speculate, to bid up existing assets, to purchase equities; activities that need not be related to growth and investment in the traditional way. It may very well be the case that when a central bank decreases its main interest rates, all that happens is an increase in credit directed towards the equity market. The extra demand pushes prices up and increases the wealth of those who own real assets. The central bank then expects those with increased wealth to reinvest their profits in the real economy thus creating jobs and real growth. When that is the case, all the central bank achieves in the long run is a major global distortion, artificially high income inequality, and misallocations of capital. In short, it stokes financial bubbles and crises. The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) believes that this is what is currently happening.

The BIS warned of the risks that come with ultra-low interest rates in its annual report and urged central banks to move towards normalising monetary policy as soon as possible. In the report, the BIS claims the world is relying too much on the effects of monetary policy, while governments are not adopting the necessary steps to generate growth.

Borrowing from the Austrian School of Economics, the BIS claims that central banks are essentially contributing to a slower recovery by entrenching excessive reliance on debt and supporting the misallocation of capital (an effect the Austrian School refers to as malinvestment). Funds are being diverted from the real economy and towards financial markets to bid up the prices of pre-existing assets. At the same time, as the current interest rate is no longer set in the free market, it sends out the wrong signals to economic agents, leading to ineffective allocations of capital between industries, and favouring long-term projects with distant and more uncertain cash flows. As soon as the rates are normalised many of these projects will show negative NPVs and will end up shutting down. The longer interest rates stay at these artificially low levels, the greater the number of unreliable projects that will be abandoned in the future. And, of course, when that happens, we have a recession.

Currently we have three main distortions that will be very difficult to solve:

- Pension schemes – the rising liabilities are ever more difficult to fund. Pensions for future generations are at risk;

- Emerging markets – these economies have been relying too much on debt to finance growth as the price of credit has been below its natural level. Under more realistic conditions, many projects will look unreliable and we risk having a currency crisis;

- Commodities – a sharp fall in commodity prices made many Latin American and Asian countries more vulnerable. Examples are Brazil and Venezuela, just to name a few.

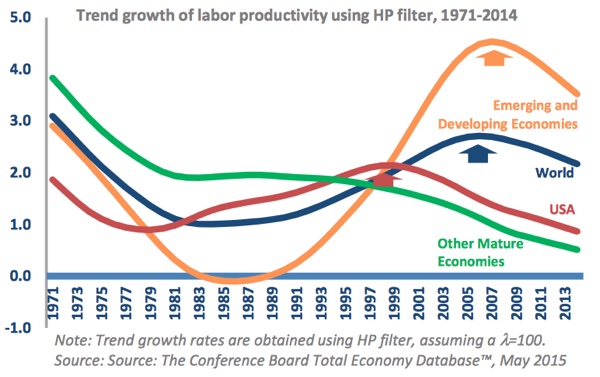

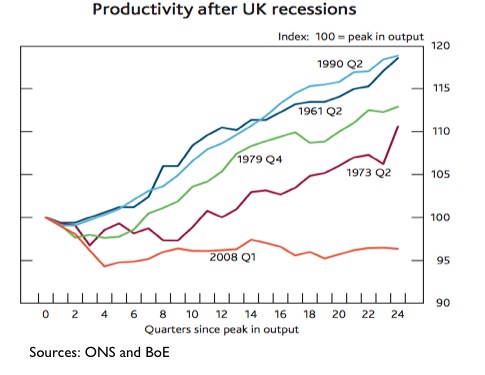

We are in desperate need of productivity growth. With a rapidly ageing population and slowing employment growth, if we are not able to increase productivity growth, our debt will become unsustainable in just a matter of years. Economic growth has been too slow since before the financial crisis, as companies have become less efficient at converting labour, machines, land and buildings into goods and services. That is a real problem in the developed world and in particular in the UK.

At a time when most companies prefer to repurchase shares rather than invest in research and development, and companies like Apple prefer to use their size to compete in existing markets instead of innovating and creating new products, it is becoming ever less likely that we will be able to spur decent growth in productivity. We need to put an end to the current low-rate policies conducted by central banks and to reformulate the way banks allocate money. For banks it is always better to allocate money to financial speculation; as for the rest of us, we badly need them to allocate the money to real investment.

Comments (0)