The Funds Hammered by Redemptions in the Wake of Brexit

Equity funds domiciled in the UK and mainland Europe have suffered their biggest client outflows for almost five years. The data compiled by Morningstar suggests that Brexit was the biggest shock to investor confidence since the Eurozone crisis in the summer of 2011.

The figures from the Investment Association are even more dramatic with retail investors withdrawing £3.5 billion from UK investment funds in June. This dwarfed the net outflows of £493 million in October 2008 after the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

The UK’s decision to leave the EU induced a knee-jerk reaction as investors reduced their exposure to riskier areas such as UK and European equities in favour of fixed income and alternative strategies.

Some investment managers suffered more than others, with M&G, Schroders, Fidelity, BlackRock and Invesco all experiencing client outflows of more than €1 billion in June. This reflects the huge amount of assets they have under management – they all have net assets of over €100 billion – except M&G, which has €81 billion – and the areas where their flagship funds are invested.

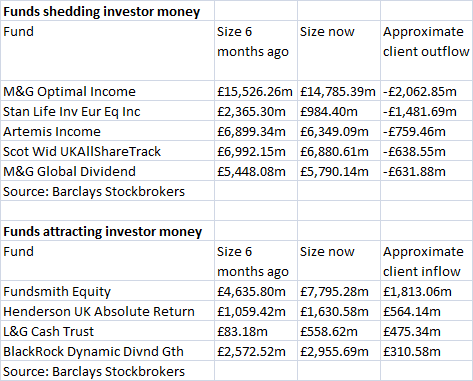

The client inflows and outflows in June were a lot more extreme than in most months, although there are some significant trends that have been going on for some time. You can see this in the fund research section of the Barclays Stockbrokers website, which shows the funds shedding and attracting the most investor money.

Their analysis compares the current fund sizes with the equivalent data from six months earlier and adjusts the increase or decrease to take account of the intervening market movements. The process is by no means perfect, but it provides a decent approximation of the net investor inflow or outflow.

The data shows that over the last six months there were five funds with net client outflows of more than £500 million, with the biggest casualty being M&G Optimal Income. This was probably affected by fears of the impact of higher interest rates on bond prices, although the threat has diminished since the referendum. There were also several equity income funds with large outflows, but these are harder to explain.

On the flipside the biggest beneficiary was Terry Smith’s flagship FundSmith Equity fund, which was the best performer in the global equity sector with a 5-year return of 160.3%. Henderson UK Absolute Return also received a lot of new money, presumably because it has the sort of mandate that can perform well in all market conditions.

According to Morningstar, the fund with the largest assets that attracted the biggest client inflows in June was Standard Life Investments Global Absolute Return Strategies (GARS), which received an estimated €207 million to take its total assets under management to €31,531 million.

GARS operates in the absolute return sector and aims to provide positive investment returns in all market conditions over the medium to long-term. It is a massive fund and invests in a wide range of liquid strategies, so it is probably better equipped to handle large client cash flows than most, although the performance has fallen away in recent months with the retail accumulation share class down around 7% since the peak in April 2015.

One of the largest funds that was worst affected in June was M&G Optimal Income, which lost €489 million of client money, although investors might have been better off if they had stayed put. The decision by the UK to leave the EU has pushed any interest rate rises off the agenda and this has enabled the fund to rally strongly, with the A accumulation share class rising 8% from the low in February 2016.

A growing problem for open-ended funds

There is nothing new about these seismic shifts in investor sentiment, although it is likely that the lower initial fund charges and easy online dealing has made open-ended funds a lot more susceptible to knee-jerk reactions.

It is now quite rare for a fund management group to levy an initial charge, but it is not all that long ago that you would have had to pay up to 5% of your money to invest in a fund, which pretty much forced you to take a long-term view. Thankfully the industry has become a lot more competitive, although if it’s encouraged investors to keep moving their money around it could weigh heavily on the performance.

The problem is that open-ended funds are not really designed for large client inflows and outflows over a short period of time, especially when they alternate from one to the other. In this situation the manager has to continually decide which holdings to sell to raise the cash and which ones to buy to invest the new money.

Each time they trade they incur transaction costs such as stamp duty on UK equities and the bid-offer spread, which are not included in the ongoing charges figure because they are impossible to quantify in advance. You can look them up in the annual accounts but by then it is too late as they will already have eaten away at the performance.

The less liquid the underlying holdings the more expensive it is. I highlighted the pitfalls of open-ended property funds a few weeks ago, but it is also an issue for other areas such as small cap, emerging market and high yield bond funds.

Investment managers can minimise the impact by keeping some of their portfolio in cash and other liquid securities, although this will not be enough when faced with massive outflows. In some cases they can also charge a dilution levy or adjust the fund price downwards – as with some of the property funds – to protect existing investors, but the performance is bound to be affected by the upheaval.

Closed-ended funds are immune from this sort of turmoil as investors buy or sell the shares on the London Stock Exchange without any cash flow implications for the underlying portfolios. If investor sentiment continues to be buffeted around it could give investment trusts a big advantage.

Comments (0)