The Fed is behind the curve

For the second time in a decade, the Fed has hiked its key interest rate target. One year after the first hike, the central bank decided to give continuity to a new tightening trend that is still expected to evolve very slowly over time. Policymakers at the FED now expect three rate rises in 2017, with the mean projected year-end rate now standing at 1.37%.

Although the market was surprised with a slightly more hawkish stance than adopted at previous committee meetings, it failed to price the high likelihood of a few important eventualities, which may lead to future surprises.

Equities are off record highs, the yen and the euro are on a downtrend, and gold is free falling. But most of these trends will most likely revert in the short term, as there is still huge optimism regarding corporate America and the FED decision was widely expected, after all. But in the medium term, risks will mount again.

One way or another Trump is recording win after win. Janet Yellen and other policy officials have been emphasizing the fact the central bank is independent from the government… and they’re quite right, in the sense that Donald Trump does not yet constitute government.

Janet Yellen and other policy officials have been emphasizing the fact the central bank is independent from the government… and they’re quite right, in the sense that Donald Trump does not yet constitute government.

The truth is that both Trump in the U.S. and May in the UK are ushering in a new era where the respective central bank may have a lot less scope to deploy unconventional policy measures than it had during past government tenures.

In the end, Yellen hiked the Fed target rate from 0.25-0.50% to 0.50-0.75%, while tweaking the policy statement language into a more hawkish tone, opening the way for further rate hikes in 2017. Coincidence or not, we have been observing larger rate and yield movements since Trump was elected last month than for the rest of the year. In a way, Trump’s twitter account may say more about future monetary policy than the FED policymakers’ testimonies.

The FED lifted its GDP growth estimates from 1.8% to 1.9% this year and from 2.0% to 2.1% for 2017, and anticipated an unemployment rate of an average of 4.5% during the next three years. The last employment report saw the unemployment rate decline to 4.6%, which is already below the estimated natural rate of unemployment (NAIRU) held at 4.8%. With the PCE core price rate (the FED’s preferred inflation measure) pointing to 1.7%, there aren’t many reasons to keep interest rates at historically low levels.

Although the FED was unanimous in its rate-hike decision, FED officials also hiked their average rate prediction for 2017 to 1.37%, a number that, while being greater than the 1.31% figure expected in the September meeting, is still a very small upgrade on the previous figures. If we look, for example, at the March meeting, when the average prediction for the 2017 interest rate was 2.04%, we quickly understand that policymakers are not only predicting small rate hikes but also dramatically overestimating the real path followed by the FED.

Trump’s twitter account may say more about future monetary policy than the FED policymakers’ testimonies.

Despite last year’s predictions for a few rate hikes in 2016, the FED ended up waiting one full year to hike its key rate, and by the smallest margin. The market reacted in a soft way despite the hawkish tone used in the statement, as recurrent overestimation of rate hikes by policymakers has been the norm.

But at a juncture where unemployment is below its long-term rate and inflation is at 1.7%, one may very well ask whether policymakers are again overestimating the pace of rate hikes or, on the contrary, are being too conservative.

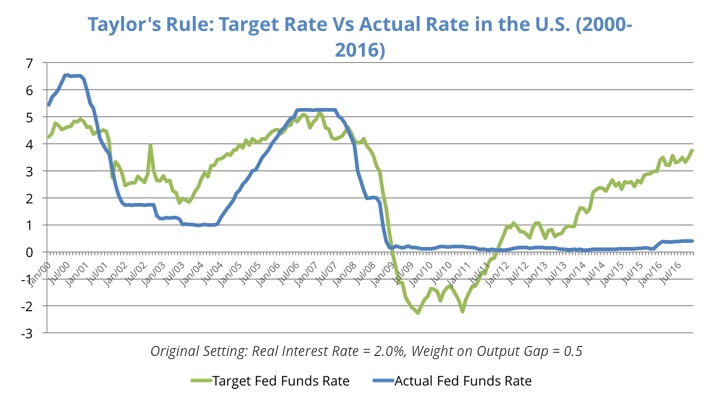

When evaluating the credibility of policy rates, I always like to bring the Taylor rule to the table. The rule basically dictates the expected central bank reaction in terms of policy rate to an output gap (or an employment gap) and to an inflation gap.

The concept is straightforward. When output is rising faster, or when unemployment decreases below its long-term rate, wage pressures start mounting and the advised policy rate rises. By the same token, when the observed inflation rate rises, nearing its 2% target, the advised policy rate also rises. If we load the Taylor rule using the standard form Taylor gave it in 1993, we come to something close to what is depicted below.

The rule has been prescribing higher policy rates than the FED has been setting since long ago. The prescribed rate for the end of year since 2011 has been 0.8%, 1.6%, 2.5%, 3.0%, and 3.8%. By now, the Taylor rule estimates a 4.0% long-term nominal interest rate, as PCE inflation is not far from 2.0% and the unemployment rate is below long-term levels.

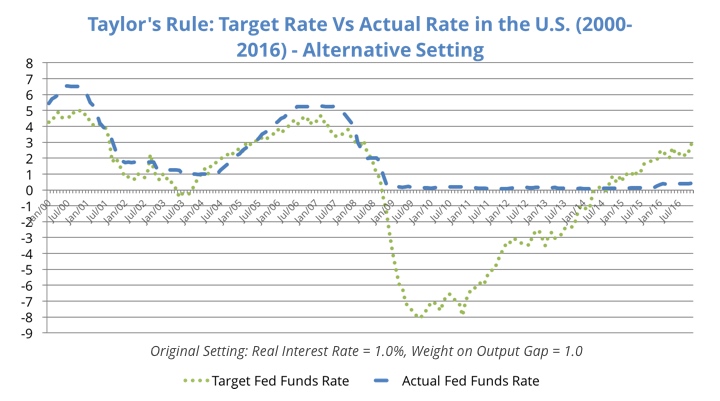

But some policymakers, which include the past FED Chairman Ben Bernanke, believe that more weight should be given to the output gap than Taylor gave in 1993 and that the long-term real rate of interest is just 1% and not 2%. If we accept this assumption, it justifies lower policy rates than the previous rule, and fits almost perfectly with what Bernanke has done. Just take a look at the new setting in the following figure.

Notice that the prescribed rate points to a large negative value, in particular between January 2009 and December 2013. When that happens, the central bank can’t just push the rate to -2% or -6% but instead needs to adopt unconventional measures as Bernanke did, which include a massive asset purchase programme, or quantitative easing.

In practice, the FED started buying mortgage backed securities in November 2008. On December 2013, just before leaving, Bernanke announced the FED would start tapering its asset purchases in January 2014. The real policy action fits almost perfectly with this second Taylor rule setting.

…policymakers are not only predicting small rate hikes but also dramatically overestimating the real path followed by the FED.

Taking the above rule forward, the prescribed rate for 2014, 2015 and 2016 is 0.8%, 1.9% and 3.0% respectively. Again, the FED seems to be way behind the curve, allowing the economy to overheat through lagging behind in terms of its key rate targets. Almost no tweak to the Taylor rule can justify the current low rates.

Janet Yellen has been giving the impression that the FED may allow the economy to overheat a little bit more while inflation is still under control, as this could help discouraged workers to return to the workforce. But, after such an extended period of abundant liquidity, there are huge risks in doing so.

Because of the lag effect, inflation may start rising quickly and force the FED to tighten abruptly, causing another financial crisis and recession. At the same time, FED officials’ projections don’t take into consideration the Trump effect. That means they largely ignore any infrastructure spending and fiscal loosening Trump may attempt (as he promised during the campaign), which would require a faster tightening.

Taking all this into account, I believe that this time FED projections may very well underestimate future rate hikes. I see inflation rising faster than expected due to the overheating of the economy that the FED seems to not been aware of (or at least to be ignoring). If that happens, bond prices will crash.

At this point I retain my positive view on bank stocks and negative view on bonds. As I mentioned in “Investment Themes for Trumponomics” in the last magazine issue (pp. 30-37), a good way of profiting from an upward move in the yield curve is by selling long-term bonds. One good option is to purchase the Proshares Short 20+ Years ETF (TBFNYSEARCA:TBF).

Comments (0)