The strange case of the Swedish taxpayer

In general, taxpayers try to minimise their contributions to the government budget, either by optimising their tax rate or through trying to delay payments wherever they can. But something strange seems to be happening in Sweden. The country seems to have been gripped by some form of mania that has led the taxpayer to overpay on his financial obligations to the government.

In 2016, instead of generating a budget surplus of Skr.45bn (£4.0bn), the Swedish government accumulated Skr.85bn (£7.5bn) as businesses and individuals paid Skr.40bn (£3.5bn) in excess taxes. Consequently, the government no longer needs to tap markets to finance its expenses, as it is instead being financed by the taxpayer. How generous! While excess payments must, at some point, be returned to the taxpayers, the money is available for the government to spend it elsewhere for some time.

The above story would make for some great headlines and serve as a lesson in generosity and altruism, but it hides a very different reality, where the taxpayer overpays his taxes in pursuing his best interests, at the expense of the government. What taxpayers in Sweden are engaged in is a form of arbitrage, as a side effect of negative interest rates and large-scale asset purchases.

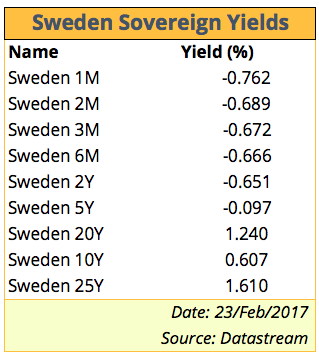

In February 2015, the Riksbank pushed its repo rate to -0.10% and later cut it further to the current -0.50% level, in an attempt to prevent an appreciation of the Swedish krona and the potential deflation that it could bring. Thus, interest rates across maturities declined substantially and investors can no longer find any positive yield on safer securities. The Swedish government is currently being paid to borrow from investors on maturities up to 5 years. The yield on a 2-year sovereign is -0.651% and even higher for shorter maturities. With inflation still positive, anyone investing in these safe assets will see his money holdings decline over time. Deposits at banks are not much better, as the best deal in town is to not be charged for the deposited money. But when the amounts are large, the rates go negative. Investors are paying to keep their money safe.

With the government having approved legislation requiring itself to pay a 0.56% interest rate on any excess payments from taxpayers, there is a huge arbitrage opportunity, particularly for businesses. Instead of paying interest at a rate of around 0.65% to keep their money safe, they now overpay their taxes and receive interest at the annual rate of 0.56%.

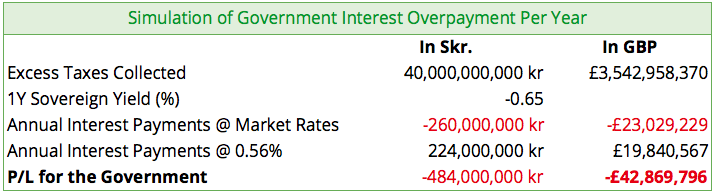

Taxpayer payments put an excess Skr.40bn (£3.5bn) in the government’s hands last year alone, in what constitutes involuntary borrowing. The government is paying interest at an annual rate of 0.56% when it could borrow from the market at around -0.65%. If we do some simple sums, what this means is that the government is spending around Skr. 260m in interest payments when it could be collecting Skr. 224M, if issuing a bond with nominal value equal to Skr.40bn (£3.5bn). The tax overpayment represents an annual loss of around Skr. 484m (£42.9m) for the government.

To eliminate the arbitrage opportunity, the government has now scrapped the 0.56% interest rate it used to pay on excess taxes. From now on, excess payments earn nothing. While the measure may prevent individuals from overpaying, it certainly won’t prevent businesses from doing it. When weighing the possibilities, it is always better to get nothing than to invest in a sovereign at a negative yield.

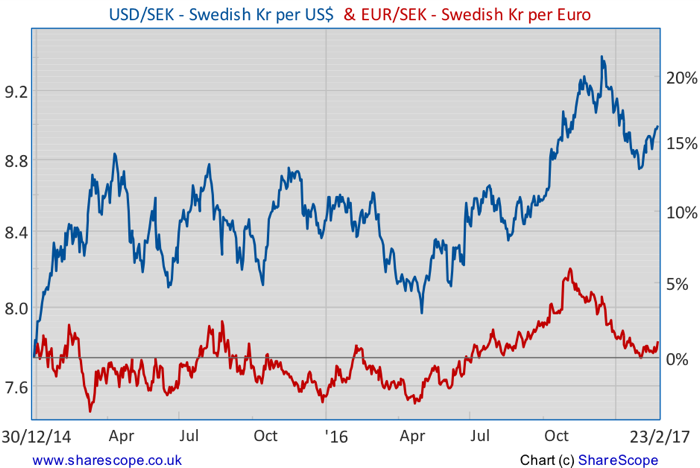

Since the end of 2016, the krona has been gaining some ground, as the Riksbank showed some internal divergence regarding future policy action at its December meeting, giving rise to expectations of rate hikes occurring sooner than investors were expecting. But, as the central bank became concerned with the negative impact the rising krona could have on prices, it adopted a much more dovish tone, opening the gate for further interest rate cuts:

“To ensure inflation stabilises around the target, it is necessary for economic activity to remain strong and for the krona to appreciate at a not too rapid pace. The political uncertainty abroad is enhancing the need for monetary policy to remain expansionary”.

The Age of Monetary Madness

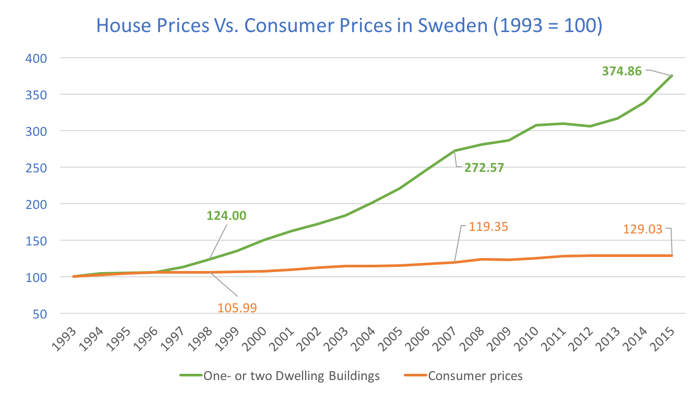

It seems to me that central banks need to find alternative ways of conducting their policy and alternative measures for inflation. When a central bank pours money into the economy, that money must flow somewhere. Just because this is not captured by CPI measures, it doesn’t mean it isn’t happening. Can you guess where the money is flowing to? Just look at the following chart.

With borrowing rates around zero, everyone is bidding up house prices. In urban areas like Stockholm, where supply isn’t able to keep up with demand, people buy houses from photos sent via email and mobile phones without ever visiting them. Such is the fear of losing the house to the next buyer.

After crashing in 1992, house prices have been rising steadily. In the 23-year period 1993-2015, house prices rose in every single year but 2012. In that particular year, prices declined a ridiculously small 1.3%. In 2015 alone, they jumped 10.8%. In the entire period, consumer prices rose at an annual pace of 1.11%, while house prices rose at a pace of 5.91%. A gigantic bubble is forming, just waiting to be popped in the very near future. Given the fact that household debt in Sweden is among the highest in the world (around 85% of GDP), I wonder what would happen if the Riksbank normalised its policy.

With such high levels of leverage in the real estate sector, when the deceleration starts it will most likely lead to a huge rise in unemployment, and economic collapse. By then, it will be much more difficult for the Riksbank to deal with the issue if interest rates are not high enough to allow for substantial cuts. This is why we are heading into a world where cash will be made illegal and all transactions will be forced through electronic systems. In such a world, the central bank may well charge 5%, or maybe 15%, annual interest rates…

In the meantime, I believe investors should be wary of the Swedish market. Everyone seems to be expecting the repo rate to remain at the current -0.5% level for the next two years, but the Swedish economy tells a different story. Inflation is mild and below the central bank target at 1.4% but much higher than it was a few months ago. GDP is growing at a pace of 2.8%, and while the growth rate has declined for three consecutive quarters, it still is much better than what can be found elsewhere in Europe. That means the Swedish economy may be closer to full employment than many think, and in turn, that means that monetary policy normalisation may come sooner rather than later. If that is the case, the real estate bubble may start deflating very soon, and bubbles usually don’t deflate smoothly…

Comments (0)