Eurozone Is A Victim of Basel III

Many are those scratching their heads at the ECB, trying to understand why is there no inflation and how the central bank can act to boost the economy towards healthy growth. But while they spend too much time digging in their neighbours’ backyard (aka the global economy) they’re the only ones to blame, as the key to this puzzle is just under their noses. They have been so busy in trying to prevent another financial crisis that they have arrested economic growth.

The financial crisis showed us just how vulnerable the real economy is to financial shocks and how dependent we all are on the banking sector’s will. It doesn’t really matter what the central bank plans to do in terms of policy, because there is no relationship between the base money it creates/destroys and the quantity of money held by the non-financial sector. What lies in between is credit, and that is in the hands of high street banks. They decide how much credit to grant and which sectors to favour. The central bank sets the short-term interest rate in order to increase or decrease the incentive for banks to expand credit; but past evidence shows that the interest rate explains too little. Banks will keep expanding their balance sheets as far as they see an opportunity to lend money (see the Iceland case for example). This means that the most important variable that dictates the behaviour of credit is the economic cycle. When the economy is expanding, banks will keep expanding their supply of credit while they reverse such action under depression. The central bank supports such behaviour through providing a liquidity facility that allows banks to first lend money and then only after seek the necessary reserves, which in an expanding economy it can always obtain due to the sky rocketing collateral values. Banks do act pro-cyclically. As far as investment in real assets depends heavily on credit, the central bank’s behaviour is also pro-cyclical.

In a certain way, and because short-term interest rates are managed by the central bank, higher levels of investment would tend to be associated with higher interest rates. The reason is very simple: investment expands when the economy is performing well, which is often when the central bank is also hiking its base rate. By this token, a lower interest rate won’t have a significant impact on real investment. When the central bank lowers its key rate, it eventually has a positive impact in the price of financial assets and then indirectly on disposable income, aggregate demand, and also investment. But if there is no impact in aggregate demand, businesses won’t invest more just because interest rates are lower. They would more likely use the excess liquidity to pay higher dividends, higher salaries to management, and replace equity by debt. But to invest more they would still need to foresee an increase in demand. At the same time, even if businesses are willing to invest more, there is still another check, as banks will ultimately determine if they’re willing to lend or not.

The above is extremely important in order to understand what may be happening in Europe in particular, where the central bank keeps expanding its balance sheet and the economy still struggles to grow. The lack of a strong link between interest rates and real investment helps understand why the central bank has not been able to boost investment in the Eurozone. The lower interest rate contributed to a strong recovery in the price of financial assets after the 2007-2009 crash, but it has not ignited a real recovery. After all, the wealth effect is not all that important in Europe, where capital income is not an important source of income for households. At the same time, we shouldn’t forget that many Eurozone countries tightened fiscal policy to reduce debt, which contributed to depress aggregate demand even more. Only when aggregate demand recovers will investment follow suit. The central bank lacks the tools to induce an increase in aggregate demand. All it does is distort the economy, redistributing wealth and creating financial bubbles, as the excess liquidity goes almost entirely to boost the price of financial assets. The current monetary easing just forces banks to accept lower returns, as it doesn’t prevent them from investing heavily in debt securities issued by governments and highly ranked corporations instead of lending to the small and medium-sized companies that represent the vast majority of the Eurozone economy.

But the problem with real investment is not only related to a lack of aggregate demand. As I mentioned above, investment depends on credit, and credit is in the hands of the high street banks. They’re not willing to lend during difficult times because they foresee a high rate of non-performing loans. But there is another big reason why they’re not willing to lend: banking rules. As Erkki Liikanen, governor of the Bank of Finland explains:

“When we assessed the capital requirements [of banks] on the basis of risk-weighted assets, [we saw that] housing has very low risk-weights but small and SMEs have very high risk weights… But if we look at our experience of the crisis, housing has been the biggest source of problems — so perhaps there is something wrong there. You should be able to diversify risks if you have many SMEs that you finance, but with housing you have to be careful, because bubbles are very heavy because they have a deep impact on a whole population.”

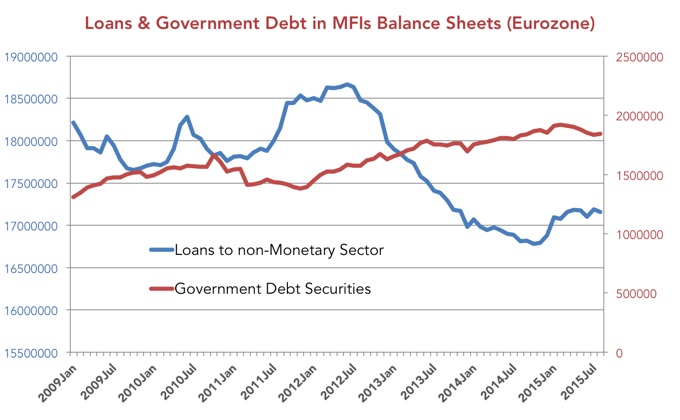

The financial crisis highlighted the need to better regulate the financial system. The securitisation the banks engaged in resulted in a complete failure to determine the market value of assets and undermined risk metrics. This time policymakers want to tackle the full picture and significantly reduce the risk emanating from banks’ balance sheets. Unfortunately they went a long way in depriving banks of their main role, turning them into a large repository of government debt.

The approved Basel III rules are based on three main regulatory principles: (1) government debt carries the lowest risk and is thus safe in unlimited amounts; (2) real estate carries low risk, and can constitute a significant part of a bank’s portfolio; (3) corporate debt is toxic and should be heavily penalised. The need to increase accountability and transparency was at the roots of the above principles. Of course it is relatively easy to value government debt as it is quoted in real time in financial markets. But that doesn’t mean it is desirable for a bank to carry such debt in its balance sheet. We need banks that are able to lend money to corporations which have real investment projects and not banks that only serve to finance governments and real estate. Basel III built the foundations of a government debt bubble and is one of the main reasons why the European economy is lagging behind others. Unlike what happens in the US, where companies get the majority of their financing from issuing debt to financial markets, in Europe the small to medium-sized companies heavily rely on banks. When banks find it costly to lend, and replace corporate lending for government securities, we cannot expect much in the way of investment.

The ECB is now committed to conduct stress tests in order to test whether our banking system is crisis-proof. But they went too far in establishing rules that just contribute to turning banks into worthless institutions. The rules favour the existence of collateral and assets that are easily valued. Real investment often does’t have collateral and is difficult to value. A company project isn’t quoted in real-time and thus requires a high degree of judgement. The ECB requires banks to adjust their capital ratios to the risk incurred, heavily penalising these kinds of loans. Banks are then pushed to hold large amounts of sovereign debt, which does not require them to constitute provisions for non-performing loans, unlike what happens with corporate or consumer loans. This goes a long way in explaining why European debt offers negative yields. Legislation that, at first, aimed at preventing the occurrence of financial crises is now creating huge economic distortions. Banks no longer want to lend money to the private sector but rather prefer to finance governments. While that happens, governments are required to tighten their fiscal policy. There is so much demand for so little that is offered.

With the above mix of policies, how can the ECB expect inflation? The only noticeable inflation is in government debt, which was artificially created by the ECB and the EU. But before understanding this, I believe the central bank will go even further by increasing its asset purchase programme. That’s good news for equities but no news at all for consumer inflation, investment and real growth.

Comments (0)