Danmarks Nationalbank tightens policy… really?

Last week, The Danmarks Nationalbank increased its deposit rate by 10 basis points in a move towards policy normalisation, particularly in regard to interest rate spreads against the ECB. In terms of the Danish economy, this move means almost nothing because short-term interest rates will continue to move within the negative interest rate policy (NIRP) framework and banks won’t touch their medium-term rates; but in terms of the external puzzle, it gives us a few more clues that the ECB is going to stand still in its next meeting(s), otherwise the Nationalbank would look like a fool. Were the Nationalbank expecting any change in rates or in the asset purchase programme from the ECB, it wouldn’t have touched rates.

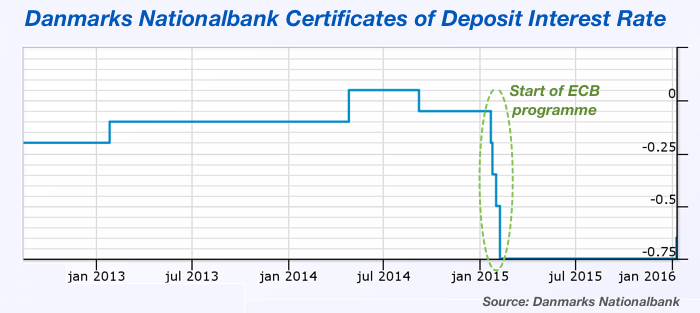

The Nationalbank hiked its deposit rate from -0.75pc (a level that was kept for almost a year) to -0.65pc, in a move to support the value of its currency within the established limits of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM2). Between the end of 2014 and December 2015, the Nationalbank had to work hard to prevent massive capital inflows, as the trillion-euro asset purchase programme announced by the ECB ignited chaos in the Eurozone’s neighbouring countries. In spite of such a programme, the Riksbank, the SNB, and the Danmarks Nationalbank all had to move to negative interest rates to prevent massive currency appreciations that could impart nefarious consequences on their trade with the Eurozone. But when Mario Draghi under-delivered in the latest ECB policy meeting held on December 3, all these border countries breathed a sigh of relief. Draghi announced a cut of 10 basis points to the ECB deposit rate and a six-month extension to the central bank’s public sector purchase programme (PSPP). Both decisions fell short of the market’s expectations, which helped reverse the decline of the Euro and remove the need for further rate cuts in border countries. In the case of Denmark, the central bank even had to purchase Kr. 49.6 billion to support the value of its currency, as capital flows changed direction, this time towards the Eurozone.

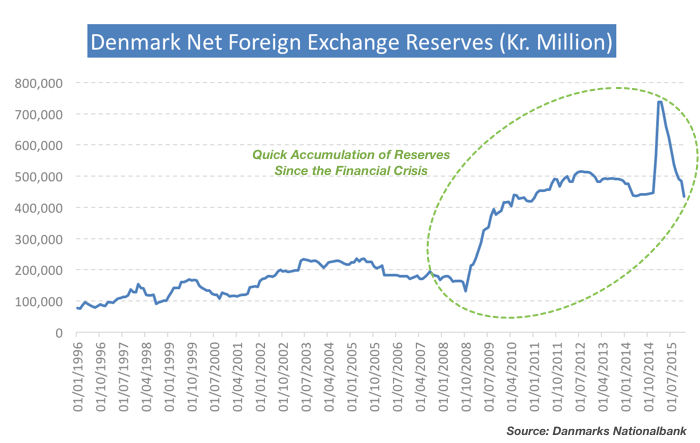

The net foreign reserves held by the Nationalbank are finally decreasing and approaching a level last seen in June 2014, corresponding to a time when European QE was just a glint in Draghi’s eye. The downtrend observed in net reserves led the Nationalbank to increase its deposit rate from -0.75pc to -0.65pc.

With the exception of the BoE, which retains much of its power in setting monetary policy, many other central banks at the Eurozone’s borders have seen their monetary policy arrested by the ECB’s actions. The financial and sovereign crisis felt by Eurozone countries scared investors away from the bloc and in the direction of what they thought to be safe havens. Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Switzerland were seen as better places to keep cash safe than the Eurozone. The lack of unity and the increasing prospects for a Grexit additionally enhanced the safe haven status of those countries. Money flowed in their direction and their respective central banks had to adopt measures in order to avoid a damaging impact on trade and subsequently on prices (deflation) and output (recession).

The SNB, for example, pegged its currency to the Euro in 2011, tying monetary policy to a fixed-exchange-rate goal. Others like the Danmarks Nationalbank had always tied monetary policy to a fixed exchange rate goal. In both cases, central banks were just printing as many francs and krone as demanded by the market and accumulating foreign reserves in the process, for the sake of keeping the exchange rate of their respective currencies against the euro stable. But that wasn’t enough. The situation in Europe deteriorated rather quickly in the Eurozone – first, with many peripheral countries at risk of defaulting on debt payments and, later, with inflation decreasing to near zero levels. The pressure on Switzerland, Sweden and Denmark increased to insurmountable levels, forcing them to cut interest rates to negative levels while accumulating foreign reserves. An exception to the above group has been Norway, which was able to pass on the NIRP much because of its dependency on oil prices (which have been negatively impacting the Norwegian economy and thus acting as a cushion). But, the Danmarks Nationalbank saw its foreign assets increase from Kr. 166.8 billion at the end of 2007 to Kr. 212.7 billion at the end of 2008, and then to Kr. 389.1 billion at the end of 2009. When Draghi’s dream started materialising at the end of 2014, the ECB announced a Eur 1.1 trillion asset purchase programme and the net foreign position of the Nationalbank quickly increased until reaching a record high of Kr. 737.2 billion in March 2015. By then, the Nationalbank was in deep trouble and had to cut its deposit rate from 0pc to -0.75pc. The Swedes had to move similarly and the SNB abandoned its peg to the Euro.

The international picture for monetary policy seems to be changing. Central banks are pressing the breaks on NIRP and ZIRP and preparing for a contraction. It all started with the ECB on December 3 when it failed to impress and thereafter with the FED on December 16 when the central bank hiked its target rate by 25 basis points. Now we have the Danish moving on and we can eventually see the Swedish and the Swiss following suit. A normalisation of monetary policy is something natural which has occurred many times before, when the economic conditions improve and the economy recovers from recession. But what we have now is the inversion in policy without the corresponding improvement in economic conditions. Europe is submerged in near zero inflation, corporate America is struggling to show organic growth in profits, Japan is struggling to keep inflation alive, China is growing less than during the past two decades, and the king of oil – Saudi Arabia – is fighting hard to raise some cash to finance a deteriorating government budget.

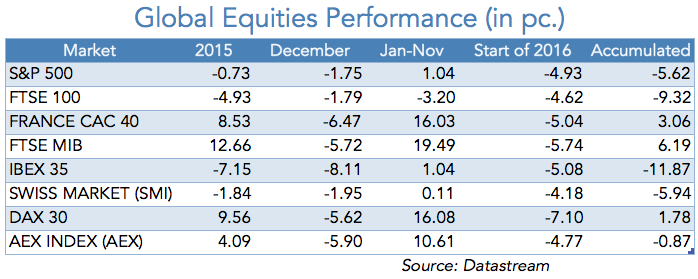

Financial markets closed last year on a very negative note and they have been experiencing a pretty nasty start for 2016.

The Dax 30 ended 2015 in the green but investors who held until today are certainly regretting not having sold out before December. At the end of November they had accumulated an annual gain of 16.1%, which contracted to 9.6% by the end of the year and to 1.8% after the first few days of 2016. And, the DAX is just one example. Investors in the French CAC 40 experienced a similar performance, with a year-to-November 16.0% gain translated into an early 2016 accumulated gain of just 3.1%. These data show us that we are living in a world full of risks, where financial markets are unable to stand on their own two feet. For these reasons I believe the recent moves by the ECB and the Nationalbank are more likely to be a pause rather than an inversion. The world of NIRP is not done yet.

Comments (0)