Central banks: are we going under again?

After more than 10 years without an interest-rate cut, the Federal Reserve is set to loosen monetary policy − but how far are policymakers willing to go?

“The Federal Reserve’s job is to do the right thing, to take the long-run interest of the economy to heart, and that sometimes means being unpopular. But we have to do the right thing.”

– Ben Bernanke, Former Chair of the US Federal Reserve

After more than 10 years without an interest-rate cut, the Federal Reserve (Fed) is set to loosen monetary policy − despite the recent growth in the US economy. However, unlike in September 2007, when the key rate was cut suddenly to avoid the collapse of the financial system, the Fed is looking to get ahead of the curve and take preventative measures. But, how far are policymakers willing to go?

The US economy is growing at a slower pace than a few decades ago, but it’s still growing. The unemployment rate is at a near record low; nonfarm payroll numbers are strong; inflation is within a healthy range; factory production and investment are at reasonable levels; equity prices are trading at record highs; and volatility is very low. Still, the Fed has just reduced its key rate by 25 basis points (bps) and indicated further cuts. Policymakers seem worried about President Trump’s trade policy and have expressed a willingness to cut interest rates, to cushion the effects of the trade war with China. At the same time, the Fed is under intense scrutiny from Trump’s administration, which is pushing hard for substantial rate cuts to support the economy.

On one side, the healthy state of the US economy doesn’t require rates to be cut, in particular at a time when policy normalisation would actually require rates to increase slightly. On the other hand, everyone expects the central bank to take the opposite action to the government’s hard-nosed measures, to balance things out. Which forces will prevail? Will Trump push the trade war to the point of no return? What can investors do and which trades are more exposed to interest-rate volatility?

Trade barriers are not a monetary problem

| First seen in Master Investor Magazine

Never miss an issue of Master Investor Magazine – sign-up now for free! |

Recent data points to softening growth of the US economy. The US president has, for some time now, been heavily advocating a reduction in interest rates. The increase in trade barriers has already resulted in higher prices for goods and services as well as a reduction in corporate investment. Still, the effects are likely to be temporary, and are better dealt with using fiscal policy, rather than monetary policy.

After a prolonged period of monetary easing, the Fed has been gradually raising interest rates, from a record low of 0.00 – 0.25% (last seen in December 2015) to a recent high of 2.25 – 2.50%. Still, after nine 25 bps rate hikes, the policy rate seems well behind its long-term level.

If the new long-term rate is 2.5%, then we can confidently say that the central bank’s strategy is risky, because the degree of margin to cut rates further is narrow.In the last two cycles (2001-2003 and 2007-2008), the Fed cut its key rate by more than 500 bps, but that was only possible because the rate was above 5% before the rate cut. At a new long-term rate of 2.5%, the room for manoeuvre is much lower.

Build-up in rate-cut expectations

There are arguments both for and against rate cuts. On 31 July, the rate was cut by 25 bps and, at the same time, the Fed dampened the most optimistic rate-cut expectations. For some time now, Trump has been campaigning for an ultra-dovish policy, challenging the Fed’s independence by threatening to fire Jerome Powell. And while the central bank’s chair dismissed these threats, many believe that Trump may get his wish, of further rate cuts.

Powell’s testimony before Congress on 10 July corroborated the view that the Fed was considering precautionary rate cuts. After the testimony, the market moved to a 50-50 chance of a series of three rate cuts occurring this year. For a few days, the expectation for a July rate cut was so high that investors not only took the rate cut as a certainty, but they also increased the chances of a 50 bps rate cut to around 40%. The higher expectations created a level of discomfort among policymakers. While the policymakers somewhat succeeded in reducing expectations for a rate hike in July, investors are expecting further rate hikes to come during the remaining course of the year.

While a cut of 50 bps would have initially ignited optimism, I believe the sentiment would have been short-lived as it would likely have been interpreted as a sign of economic weakness. The Fed will, I’m sure, take that into consideration.

How is the US economy faring?

Despite the trade-war issues and some softer economic data, the US economy is still in good shape. The unemployment rate is now at 3.7%, which is just 0.1% above last month’s numbers and near levels not seen since 1969.

The latest nonfarm payrolls report confirms the robust health of the employment market, with the economy adding 224,000 payrolls in July (figures above 200,000 are usually considered very strong). GDP growth slowed from 3.1% in Q1 to 1.8% in Q2, but much of the decrease has been attributed to trade and inventory idiosyncrasies. Despite the slowing economy, the released data marks the twenty-first in a row, of figures showingquarterly growth, as the last time the economy shrank was on Q1 2014.

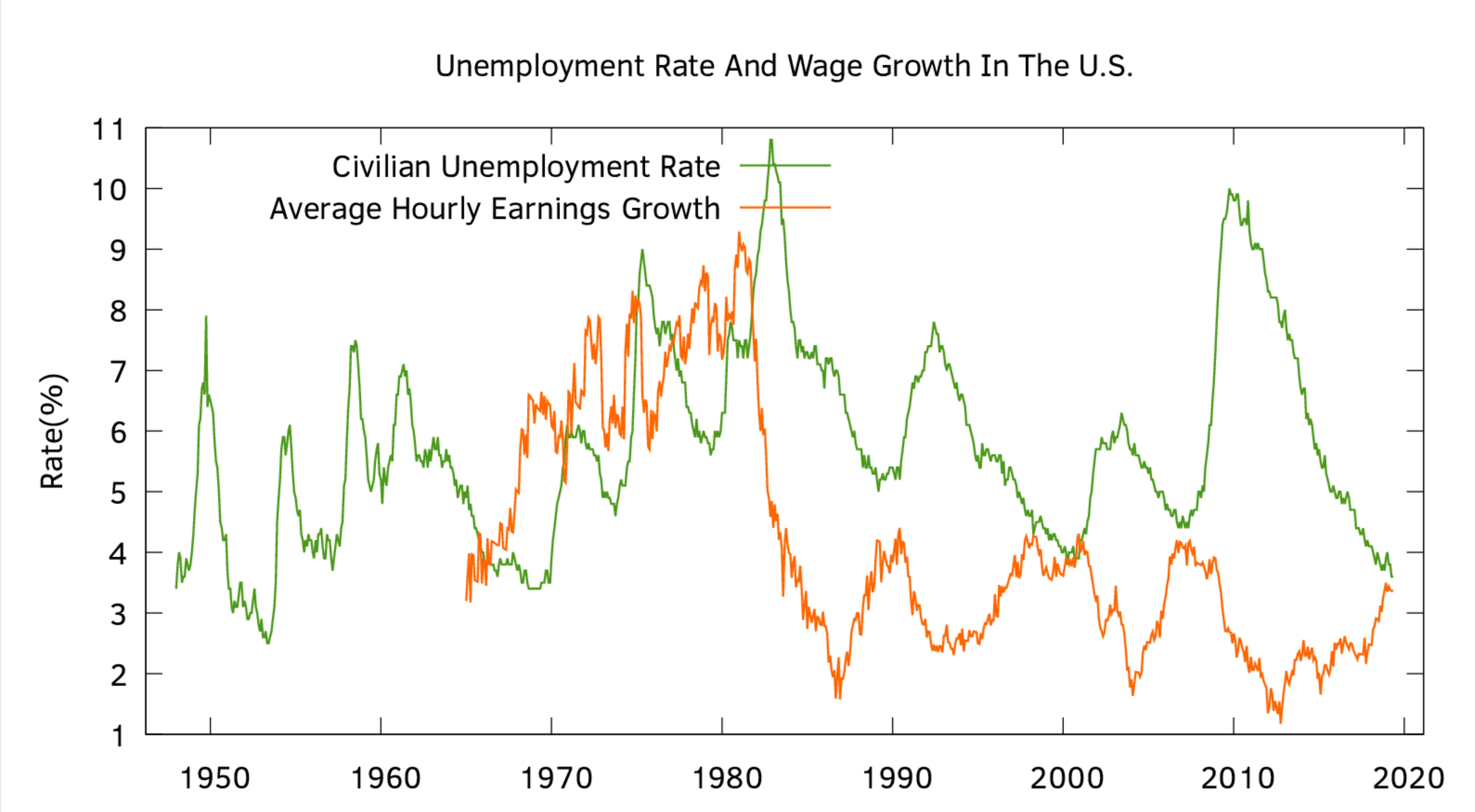

The latest inflation numbers reported by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics point to a rise in prices of 1.8% in May (year-on-year). After two years of inflation above 2%, the figure is stabilising near 2% this year. While the Fed prefers to target inflation numbers obtained from personal-consumption expenditures, it’s undeniable that prices are rising. This reality is confirmed with the evolution of hourly earnings. There seems to be a clear negative relationship between unemployment and average hourly earnings, as depicted in the chart. After weighting everything, I would say there’s more upside than downside risk for inflation, which doesn’t fit a scenario of interest-rate cuts.

In summary, it’s difficult to find reasons for the Fed to reverse its policy. I believe the central bank has just cut rates to buy some time. Trump is pressing the central bank because of his own agenda, but the central bank is still independent. Besides, monetary policy is good for managing monetary problems, which is not the case here. There’s no financial crisis, no risk of deflation and no foreseen systemic risk. Powell is just keeping all options open while avoiding fighting market sentiment.

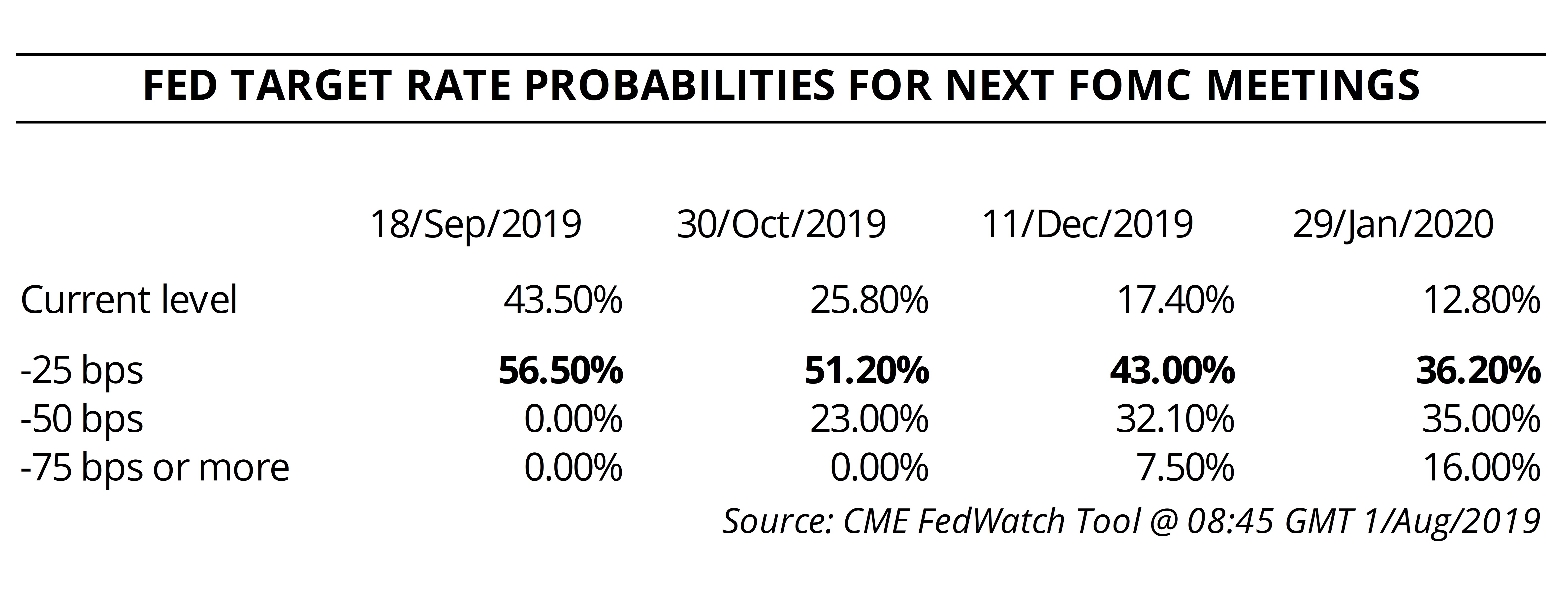

While the expectations for rate cuts corrected a little after the 25 bps cut which was below expectations, investors are still expecting too much. The Fed Watch Tool is attributing a high likelihood to a total of three rate cuts this year. The odds for a second rate cut occurring in the next meeting (an additional 25 bps cut) are 56.5%. For the October meeting, the odds for an accumulated 75 bps cut or more (an additional 50 bps or more) are now 23.0%. For the end of the year, the odds for three accumulated rate cuts (an additional 50 bps cut) are currently 39.6%, while the odds for two or more are 82.6%. The data from the Watch Tool reflects high expectations from investors regarding rate cuts. The Fed is expected to cut its key rate by an additional 25 to 50 bps this year. My view is that these odds are curved towards rate-cut optimism. If the trade wars ease, these odds will change dramatically. At the same time the depicted scenario seems to place the US in trouble. But what happens if we compare the country with Europe? With all this in mind, I believe there are a few places in financial markets where investors may be relatively safe for the next couple of months.

Placing a few trades against the crowd

My key investment themes this month are:

- A scenario of slower-than-anticipated rate cuts in the US

- A deterioration of the euro area relative to the US due to political and economic factors.

EUR/USD

In general, interest-rate cuts (or an expectation for them to happen) should lead to currency depreciation to some extent. If there is a serious risk-off event, the reserve currency status of the dollar may prevail over any rate cuts, but for a normal scenario where a few preventive rate cuts are expected, the dollar may lose some of its appeal. However, if the expectations prove too optimistic regarding rate cuts in the US, or if Europe engages in a more dovish monetary stance, the dollar may gain value against the euro.

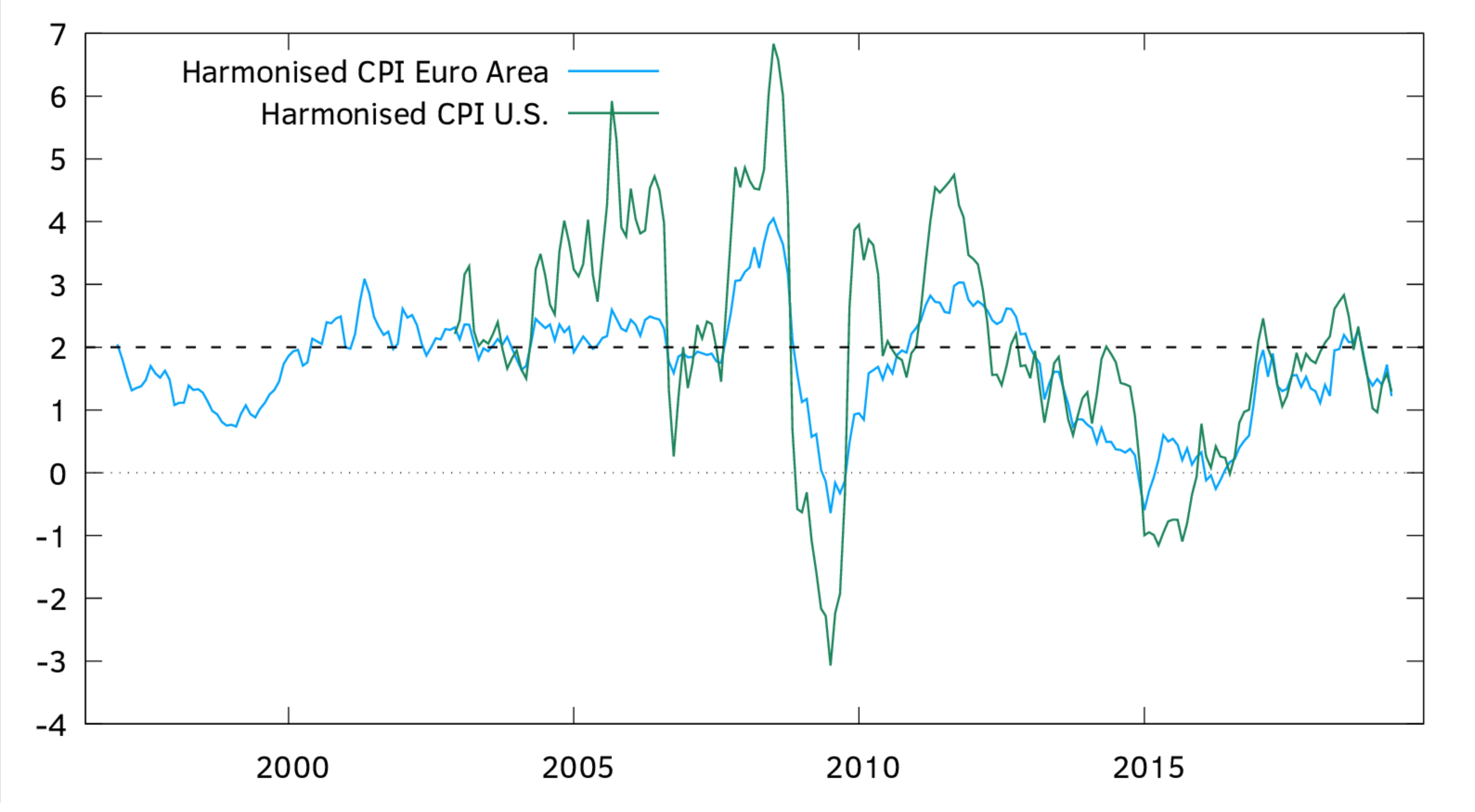

Europe hasn’t experienced the growth the US has after the financial crisis, not even after sorting out much of its fiscal trouble. And, at a time when global growth is slowing, there’s no reason to expect Europe to shine, in particular not at a time when negative European sentiment abounds. The European Central Bank hasn’t been able to hike its refinancing rate after pushing it down to the current 0.00% level.

Reflecting economic and policy developments on both sides of the pond, the euro managed to hit a high against the dollar at 1.25 on January 2018 but differences in growth between the regions have contributed to drive the euro down ever since. Some enthusiasm regarding rate cuts has been boosting the dollar a little. But such enthusiasm may prove short-lived. If not, there’s still a high likelihood of the euro area experiencing slower growth than the US, which would push the euro down. All this puts pressure on the euro side, opening an opportunity to be long on the dollar and short on the euro. By the end of 2016, the euro tested parity against the dollar. It may be tested again.

US bonds

Bonds are expected to benefit from rate cuts as yields and bond prices are inversely related. Because long-term interest rates have been low for a long time, expectations for rate cuts are having an effect mostly on the short-maturity side of the yield curve, up to three years. For this reason, the best way to trade against current expectations is by means of shorting bonds with maturities between one and three years. One possible course of action is to sell short a bond ETF like the iShares 1-3 Year Treasury Bond ETF (NASDAQ:SHY).

Gold

While it may appear controversial for some, I’m not optimistic on gold for the shorter term. Gold has been rising on the expectation that central banks would resume rate cuts. It was in particular boosted by the possibility of the Fed cutting rates three times this year. If rate cuts come short of expectations, gold may enter a correction and return to its May levels at $1,270, from the current $1,403.

Final words

After the bold measures deployed by the Fed to fight the 2007-2009 financial crisis, the central bank is now being called upon to act again. After nine rate hikes in the aftermath of the recovery, the central bank reversed its policy and cut its key rate by 25 bps. But, unlike what has happened in the past, this time there’s no financial crisis or economic downturn. The cut is mostly preventative. But the question that should be raised is: does it make sense for the central bank to cut its key rate several times as preventative action when rates are already low? For me it doesn’t, so I am willing to take an opposing stance.

Gold currently $1403? Typo or time warp?

As interest rates have been “low” for over 10 years now, is it possible that expectations of returns have adjusted as a semi-permanent feature of the bond and equity markets? If so, then won’t a 0.25% change up or down have a proportionately bigger effect than in the days when rates averaged 5%? In which case, perhaps changes within a 0 to 2.5% range will be just as effective as in a 0 to 5% range? A 0.25% change is now the same as s 0.5% change in the past.

If this argument is wrong, why is it wrong?