Capitalism versus Democracy: Robocop is on his way

One of the things that I find most irritating about the beliefs of some of those on the further outreaches of modern right-wing political belief is their habit of confusing democracy with capitalism. I can understand why they do it: consumption is for people and democracy is the people; therefore, capitalism satisfies the economic needs of the people just as democracy satisfies their political aspirations. QED.

Such loose connections are usually fused together in the minds of “neo-con” (new conservatives) who started out as far-left intellectual types who, quite reasonably, became disillusioned with their early beliefs, as a result of the old Soviet Union’s failed experiment in totalitarian socialism, and so converted to a strident non-socialist view of the world. As we all know, communism just did not work. Like contemporary banking, you just couldn’t find the right people to make it work as it should. It was a curious and significant fact that the first professional group to pledge loyalty to the Bolshevik revolutionary government was the bankers.

Most of those from what used to be called the British “working class” did not succumb to the dream of communism. That is because they were pragmatists by circumstance. They were simply not romantic or intellectual enough to be swept along by it. Moreover, they did not have a guilt complex, in contrast to some privileged middles-class individuals. Were Kim Philby and the other Cambridge University spies motivated by a sense of guilt? I assume so. For anyone with a grain of empathy, the plight of those at the bottom of the pile and the victims of old-fashioned trade-cycle capitalism would be hard to rationalise away entirely, though a few gins and tonics and lunch at Simpsons would help as an encouragement to a rosier picture of the world.

The working class had no time for romantic intellectual notions about life or guilt. ‘Neo-cons’ are those irritating, mainly American, intellectuals who urged the invasion of Iraq in the intellectually naive belief that Iraqis would wholeheartedly embrace democracy despite everything else. They were of course totally misguided. Although undeniably intellectuals, they had obviously never read any Gertrude Bell.

Most revolutions seem to have been started by the middle classes. That was true in England in the seventeenth century and in America and France in the eighteenth centuries. Forget the picture of the sans-culottes storming the Bastille; it was the disgruntled and aspiring middle classes who organised that revolt, not the peasantry.

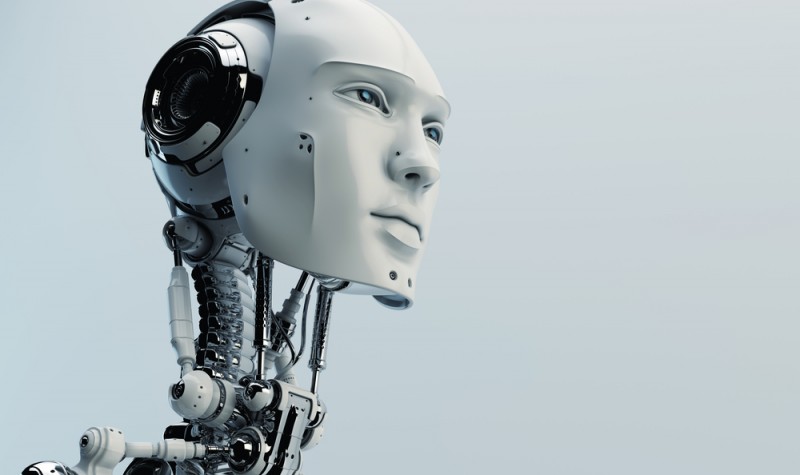

So what brings these thoughts into my imagination just now? It is digital technology and the arrival of “artificial intelligence. Last week an article in the The Times listed the number of economic activities which at this time are already shown to be done more efficiently by robots than expensively educated sons and daughters of the middle classes. The list includes both unsurprising and surprising means of employment. My own article merely extends the argument in search of the implications of such a thing. We all know about the more mundane and laborious economic tasks that machines can do. But what about those white-collared professional jobs?

Accounting, surgery, teaching and some parts of the legal profession are ripe for downsizing. We already know that parts of the judicial process are likely to be digitalised, with appearances before the court replaced by online pleadings. While being particularly suitable for dry and abstruse matters like administrative law, one can see no reason why a computer should not be programmed to find the most persuasive argument to put without it being pleaded by some costly barrister. Just input the data and a robot with or without a wig and gown can do the rest. Judgements, I presume, are equally suitable for truly algorithmic analysis.

None of this is a joke. Artificial intelligence is likely to cut a swath through the ranks of middle class employment. Great chunks of humanity will be without usefully well paid means of employment. The good news may be that there will be little need for those costly school fees, now increasingly ill afforded by the lower end of the British middle classes. So that is a relief!

And this brings us to the point. What are the educated but economically surplus to requirement middle classes to do? As we know, idle hands make mischief. Will they do what their middle class ancestors did, when confronted with injustice and tyranny? Plot and carry out revolution in the name of liberty – the liberty to earn a living? And if they do, who will suppress them? Robocops of course; that fine bit of efficient quasi-artificial intelligence prophesied long ago in the movies. And what will happen to the consumer economy when and if people do not have the income with which to finance consumption?

In answer to these gloomy forebodings, I look to the experience of history. As the world changes and advances, so too does the employment market. The worst expectations of the Luddites were not realised. There was never the great, long-term economic surplus of labour envisaged by the 19th century economist Malthus, which gave economics its woeful sub-title the “dismal science.”

Moreover, we have representative democracy to prevent such a socially shattering outcome! Will that stop it? Probably not! Given that the market, like the customer, is always right, it is hard to believe that artificial intelligence will not be with us sometime soon as economic reality. And once genies get out of bottles, it is hard to put them back in again – particularly in a situation where the owners of such intellectual property have the means to capture the democratic system.

Perhaps that power will be used to re-establish the qualified political franchise that existed in Britain before the first great franchise Reform Act of 1832? Perhaps voting rights can be rationed on the basis of how many robots an individual may claim intellectual property rights over? Or maybe, we will return to the ‘rotten borough’ system where certain constituencies are filled with franchised robots who will always vote in the interests of their owners and of course themselves? As someone once said, “I kid you not!” Humanity, in its economically useful form, has never looked so superfluous.

Logically and objectively speaking, we could be heading back to a new version of pre-consumer society economics in which the economic system largely exists to serve the limited needs and desires of a comparatively small and wealthy elite. After all, the consumer economy is no more God given than anything else!

Comments (0)