Is Kibo Mining’s Joint Venture All It’s Cracked up to Be?

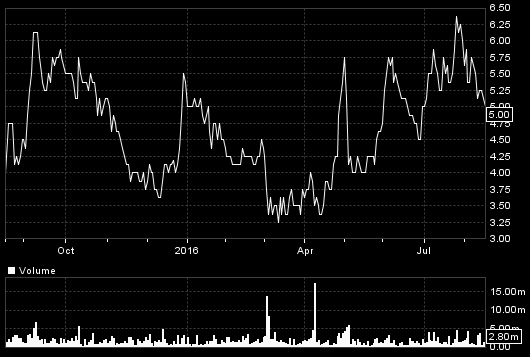

I promised to update on Kibo Mining when it published details of its joint venture with an adjacent gold miner to monetise its gold assets in Tanzania’s Lake Victoria gold fields – in order to add to whatever value emerges in its Mbeya coal to power station project. Hiving off parts of a company is supposed to deliver better value for shareholders, so how much of a bonus might Kibo’s prove to be?

To re-iterate, I follow Kibo despite its small size currently (c. £19m) because, in addition to its coal mine-to-power station at Mbeya in south west Tanzania (whose potential value to shareholders – which could be some multiple of Kibo’s current market cap – I’ve been trying to assess and compare with three other coal-to-power hopefuls, ORCP, NCCL, and EDL), Kibo has always had other minerals interests. Most, though, are pure exploration and at too early a stage to have any value but, instead, an open-ended liability to spend on exploration before any value emerges.

An exception is at Lake Victoria, where Kibo’s Imweru gold prospect, acquired in 2013 from a successor of Barrick Gold, has a partially drilled JORC resource now the subject of the JV, in which Imweru’s 750,000 oz resource is merging with a directly adjacent 205,000 oz resource at Imwelo held by Australian private company Lake Victoria Goldfields Ltd. The resulting new company will be floated on AIM and JSX as Katoro Gold Mining, after its shares have been distributed pro-rata to Kibo and LVG shareholders.

Reflecting that Imwelo’s highest category measured or indicated resource is similar in size to that at Imweru (most of which is the larger sized but lower value inferred category) and that it has a mining licence and has produced a mining plan, the initial split is 52% to Kibo and 48% to LVG. But when Katoro lists it will be to raise funds to start the mine, so existing (i.e. former Kibo and LVG) shareholders will see their holdings diluted immediately.

By how much will depend on the value attributed to their existing assets or prospects in relation to the funds being raised, and it is here where much uncertainty lies, explaining why, contrary to Kibo’s hopes that news it publishes will enhance shareholder value, the shares always fall.

The uncertainty lies in the value the market will put on the prospects the new company can show. To guess we can either find a comparable goldie at a comparable stage, or we can try to go by a bulletin board leak of some limited facts in an LVG information memorandum aimed at raising $250,000 from private investors to fund due diligence before the merger deal. We also have some past descriptions by Kibo of its plan for Imweru, and a 2014 technical report by consultants TetraTech.

The latter give only a sketchy basis on which to estimate, but are probably better than using so-called ‘in-ground’ values for gold deals where the $paid/resource varies significantly – with larger resources and better grades attracting more than four times that for smaller resources and lower grades (such as at Katoro) and where there is no information about the mining ‘reserve’, which is the solid reality that buyers will be paying for, or the gold price when the deal was struck, or whether there is infrastructure already in place. On one recent deal for a similar size and grade to Katoro, however, less that $20/oz was paid, which would imply a $15m valuation, of which Kibo shareholders would see 52%, or 2p per their existing Kibo share.

But that would be before dilution to raise the development funds, and can be compared with some other small goldies, all of whom are more advanced than Katoro with some (Kefi and Ariana) almost fully funded, despite which their projects are valued in the market at only £21m and £28m. Others like Scotgold and Galantas Gold are valued at only £12m, while Condor, with a resource more than double Katoro at much better grades, is valued at £47m.

An alternative is to ‘guesstimate’ Katoro’s listing value from that other sketchy information.

Kibo says a listing will happen within three months of the merger. But to give time to produce the technical and economic reports that will be desirable if Katoro is to be floated at the best possible valuation, the plan seems to be to initially raise only enough funds to expand the present 26% of the combined 755,000 oz resource that is measured or indicated, sufficiently to produce reports to back the main funding, which LVG says will be within 12 months of the initial listing.

While risky to predict a value for the small initial listing and fund raise, it will probably need to be more than the $5m that Tetratech said in 2014 would fund the necessary further drilling at Imweru. Assuming a $7.5m total to cover other costs against an optimistic ‘in-ground’ value of, say, $7.5m, then existing Kibo shareholders would see their Katoro shares list at 52% of 50% of the total $15 – i.e. $3.5m or 1p per their present Kibo share.

Alternatively we might estimate what the whole fully funded project would look like, and what funds need to be raised, for which we only have LVG’s information memorandum saying the Imwelo plan (before adding Imweru) was to mine initially at 17,000 oz/year for five years at a cash cost of $700/oz, and a cost including capex, of $800/oz.

In both cases, the mining will be by shallow open pit targeting the most profitable areas first, using contractors with cheap heap leach processing before a more expensive carbon-in-leach plant is installed to treat the deeper gold. So the operation is likely to be highly cash generative from an early stage and might be sufficient to fund the later capex.

But before shareholders see any benefit, the initial capex will have to be funded, which will need some sort of forecast. Here, Kibo – while describing in ‘apparent’ detail the economics (for its gold as well as its power projects) estimated by its consultants – has never given the full figures and assumptions that analysts need to make any sense of them. I always wonder whether that is because Kibo doesn’t want to frighten investors with the size of the required funding.

LVG’s original plan for Imwelo only would have implied $8.5m initial capex and (assuming gold at $1,350/oz) an annual cash profit (not the full plc profit, which will be less) of $11m p.a. for five years, producing an 8% NPV of $33m with a 127% IRR. But that is unlikely to be a very accurate while it would certainly not have included other listing and plc costs.

Instead, Kibo and LVG are now suggesting a plan to commence mining at 25,000 oz/year and to ramp up to 50,000 oz/yr ‘within 12-18 months’, with a medium-term target of 100,000 oz/yr. But at that rate the likely mining reserve would last for only 5-7 years – even if, as Kibo suggests, the total resource can be expanded through drilling to 1Moz – so considerably more drilling will be required before that ‘medium term’ output is even within reach.

Assuming an initial drilling on just Imweru to get the resource to 1Moz, plus Imwelo’s initial capex, plus corporate costs, gets us to at least $15m and possibly $20m as initial funding. Against that, the 8% NPV of, say, 700,000 oz extracted over seven years at $700/oz cash cost would be around $100m with an IRR of over 100%.

Initial listings rarely value a mining project at more than 1/3rd of its NPV, so matching $33m of that against $20m funding would point to existing Kibo shareholders seeing 33/53 of a total $53m listing value (which looks very high compared with the projects I’ve listed above). But if achieved, they would see 52% of that $33m, or 3.5p per existing Kibo share (at a $1.3/£ exchange rate).

Kibo has promised that floating off its projects will deliver ‘value’ to its shareholders ‘without diluting’ them, so I suspect they will be disappointed at the relatively low value (although a good proportion of Kibo’s current share price) at which their Katoro shares will probably start out.

Although Katoro looks capable of good profits, the initial capital to be raised (project finance for such a small mine is unlikely to be forthcoming) will always produce dilution, even if at the subsidiary level (i.e. Katoro Gold) and not at the Kibo plc level. The net diluting effect on shareholder ‘value’ is the same.

That disappointment will be reinforced by the timing. Announcements so far point to 15 months after the merger completes before the main funding, following which LVG quotes ten months to order the processing plant. Assuming another year before production ramps up gives three years before Katoro shareholders will see any value start to emerge.

My estimates are unreliable. But how I arrive at them might be a guide for investors should more detail be released.

Comments (0)