Shaken Not Stirred – an introduction to the bubbly world of cocktail-shaker investment

Featured in this month’s Master Investor Magazine.

In the civilised decadence of the Roaring Twenties and Dirty Thirties, any person in possession of a cocktail shaker was a person ready to party. But where did this ingenious little bar tool originate and how come everyone aspired to own one?

The origins of the mixed drink and the essential accessory with which to blend it began with the ancient Egyptians: they combined herbs, spices and alcohol to make medicinal remedies. In 1520, Hernan Cortéz, the conqueror of Mexico, became partial to a New World potion with a base of cacao which was served to him from a tall golden vessel.

In America in the late 1700s, the brewing of different liquors was the precursor to the punchy combos we enjoy today. But how did the cocktail get its name?

Legend has it that a widowed innkeeper named Betsy Flanagan was having a bad time with her chicken-rearing neighbours. To teach them a lesson, she stole their prize rooster which she killed and cooked to serve to her customers. A bunch of rowdy French and American soldiers washed the tasty meal down with a drink Betsy concocted and decorated with tail feathers. As the evening wore on and the boys got merrier, they demanded ‘more cock tail’ and the rest, as they say, is history.

As early as 1806, in the May edition of a New York publication entitled The Balance and Columbian Repository, this new fangled beverage was described as “a stimulating liquor, composed of spirits, sugar, water and bitters supposed to be an excellent electioneering potion in as much as it renders the heart stout and bold, at the same time that it fuddles the head. A person having swallowed a glass of it is ready to swallow almost anything else!”

Mixologists of the day experimented by adding fruit juices and sodas to bottled drinks such as gin, martini, vermouth and whisky. Merging the flavours by moving the liquids back and forth between two tumblers, they soon realised that something a little less clumsy and a little more practical was needed. And so the true evolution of the decorative cocktail shaker began.

The earliest of these inventions were native New Yorkers much like their promoter, Mr. William Hartnett. He applied for a design patent in 1872 for an ‘Apparatus for Mixing Drinks’. This was a three-piece gadget comprising a built-in strainer, a cup and a cylindrical base that all fitted neatly together. The contraption was later simplified to just two pieces: a tall base into which the ingredients could be added to chunks of ice for speedy cooling and a cup-shaped top with a built-in sieve. The subsequent shaking combined the contents and the sieve stopped the ice cubes from tumbling into the glass. Ice could be popped in later if required.

In 1887 The International Silver Company listed six sizes of the standard two-piece shaker in their catalogue. By the turn of the 20th century, the Victorian-style shaker, not unlike a tea or coffee pot, had become a bar-room fixture. Grand hotels in the USA were keen to compete with the British convention of Afternoon Tea so they came up with the slightly more outré Cocktail Hour.

That time of day, a pre-prandial cinq à sept, earned its reputation as a way to fill the gap between tea and dinner. The custom was embraced with gusto.

Advertising agencies jumped onboard with slogans like: “… puts new life into the tired woman after a long day’s shopping” or the even catchier “… designed to boost your husband when he comes home late from work.”

Barmen soon became showmen as they brandished their shakers high in the air like maraca players. The rapid rattling of ice cubes was a satisfying and anticipatory sound, tempting the taste buds with the latest creations from the bartender’s fertile imagination. A natural progression was to serve cocktails at home and before long, no self-respecting household was complete without a bar full of blending equipment not least of which was a collection of shiny shakers.

Matching drinking cups, citrus presses, stirrers, ice picks, scoops, tongs, strainers and muddlers were thrown into the mix and the expression “Anyone for cocktails?” became music to the ears, a pleasure that could be enjoyed by men and women in equal measure leading them through to dinnertime ‘in high spirits’.

Exotic names like Angel’s Delight, Boston Iced Tea, Bronx Express, Cowboy Martini, Floridita, Margarita, Moscow Mule, Prairie Oyster and Singapore Sling fuelled the fire for all things fancy, foreign and frolicsome. As Dorothy Parker, the great American writer, poet, critic and doyenne of the witty riposte said:

“I love a Martini, but two at the most,

Three, I’m under table

Four, under the host!”

In 1908, Harrods advertised two silver-plated cocktail shakers in their brochure “for mixing American drinks”. High end houses like Cartier, Tiffany, Mappin & Webb and Asprey followed suit and the great jewellers and silversmiths of the time competed to design novelty shakers to rival the ever-growing plethora of bar room accessories.

Cocktail shakers were given as Christmas and birthday presents and awarded to sporting heroes. They were shaped like fire extinguishers, ladies’ calves (shake a leg?), Zeppelin airships, WW1 bombs, army tanks, lighthouses, golf bags and skyscrapers inspired by the New York City skyline.

During Prohibition (1920–1933), when alcoholic beverages became illegal, cocktails were still consumed in bars called Speakeasies. The quality of the liquor available was inferior to before and there was a shift from whisky to gin; the latter did not require ageing and was therefore easier to produce illicitly. Honey, fruit juices and other flavourings helped to mask the foul taste of the poor quality spirit. Sweet cocktails were easier to drink quickly which was quite a consideration when the establishment could have been raided at any moment.

The Great Depression of 1929 stilted manufacturing and sales but once the economy picked up and Prohibition was lifted, glassmakers like The Cambridge Glass Company of Ohio added flair to a new range of styles in ruby red, cobalt blue and emerald green glass with recipes and measures etched or silk screened on the sides.

Jazz Age figures frolicked around the circumference while golfers, polo players and aviators showed off their prowess in paint or inlay. Cocktail shakers wielded by flamboyant bar tenders appeared in movies and became associated with the glamorous lifestyles of the movie stars. The stylish shaker became a de rigueur symbol of sophistication and the good life.

So, what to look out for and what to collect? As with any purchase for investment, there are only three requirements: quality, quality and quality. Go for the luxury labels mentioned above if you can afford them – they hold their value and have more chance of appreciating than everyday examples.

If you like glass, the Cambridge Glass Company’s Rose Point, Gloria, Diane and Wildflower patterns are popular and very affordable. A vintage Wildflower design with a chrome lid is currently for sale on eBay at around £60.

S.W. Farber’s ‘Farberware’ and Farber Brothers’ ‘Kromekraft’ range are also excellent starter models. They are fairly standard in design with an Art Deco Farberware 12” chrome model comprising pitcher and lid currently on sale on eBay for around £18.00.

If you want to create a serious collection, however, you’ll need to dig a little deeper. The Penguin is a highly collectible character as he was a 1930s mascot. Dressed in a tuxedo with a hinged beak that lifts up to reveal a stopper and pouring spout, he symbolizes the elegant man about town. I would guess this figure was chosen as much as for his ‘penguin suit’ as for his cold climate connotation, representing a well-chilled cocktail.

A good quality silver plate penguin-shaped shaker sells today for around £1,300. Look out for the Napier label, originally introduced during the holiday season of 1936. Other shakers with a good provenance are classic architectural designs by Norman Bel Geddes.

Asprey of London is currently selling a rocket-shaped shaker for £7,500 and Pullman Gallery of King Street, St. James’s has a wonderful, eclectic selection from around £2,000 upwards. The auction site 1st Dibs is another great shopping source offering a variety of models and prices.

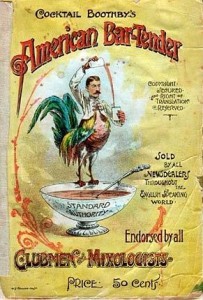

Books also abound on the subject for you to do your research before you buy. Here’s a quote from San Francisco writer and bartender William “Cocktail Bill” Boothby’s 1891 tome:

“Do not serve a frosted glass to a gentleman with a moustache. The sugar will adhere to that appendage and cause great inconvenience.”

Cheers m’dears and bottoms up!

Wendy Salisbury is a London-based antique dealer, author and broadcaster with a passion for collecting eclectic objets d’art for investment. “I’ll buy anything I can fit into the boot of my car if I think there’s a profit in it!”

Comments (0)